The Video of a Lifetime

John Haberin New York City

Mary Lucier and Cauleen Smith

Harold Cohen and AARON

When video art extends to nine channels and the breadth of a gallery, one can fairly call it an immersive experience. For Mary Lucier, it is Leaving Earth, but it is not transcendental. It is far too rooted in this world.

At age eighty, she is revisiting memories from before and after her husband's death. It might be her return to earth after a forced absence. It makes her losses all the more telling and more real. It also shows how wonderfully a multichannel video can and cannot encompass a life. Cauleen Smith makes the same point for life in LA with a blueswoman to guide it, but one is less likely to fall for the illusion or to pierce it. Is this really the video of a lifetime—or will the future belong to AI?

Once artists had workshops, with assistants to grind pigments, to prepare a painting's ground, and at times to paint. Now they may have only a studio and a computer. They may work out their thoughts on it, in virtual sketch pads. They may even call the results art. Harold Cohen does, but he leaves the software to carry out the details, with plotters as its pen and acrylic for color. It gives him a dual canvas for his own art, in software and, ultimately, on the wall.

Cohen, then close to forty, got the idea at the University of California, San Diego back in the 1960s, and he set out to make it real. By the 1970s it had its own exhibition and a name, AARON (like, I presume, AI-ron). It has new relevance today, when people cannot talk often enough about their fears and hopes for AI. It also has a retrospective at the Whitney, but what exactly is it? Is it an assistant, a collaborator, a competitor, an alter ego, a friend, or simply a medium? Could it have, like an assertive child, a mind of its own?

Returning to earth

Mary Lucier came early to new media, and she has been working in both single and multiple channels for some fifty years. (How could MoMA have left her out of "Signals," its survey of video as installation and installation as video?) Earlier still she was a member of the Sonic Arts Union, and what could be more immersive than sound? Still, immersion suggests a single, unified experience, of a place and time, like LA for Smith or the Canadian landscape for Michael Snow. It suspends one between the space of the gallery and the artist's vision. How could it ever leave this earth?

To be sure, a wide screen in a dark room can carry one into the sky and into the night, as with Buried Sunshine from Julian Charrière north of Chelsea. It becomes a virtual hymn to creature comforts and convention. Lucier, though, provides scant comfort. She sets her monitors at varying heights and positions throughout the gallery. One on the floor could pass for a burial slab, and it does bear text. Only the lone monitor at your back confirms that you have in any way entered, and a place among the rest would be at best a tight fit.

If that were not worldly enough, they show her in a realm she calls home. She spends much of her time in Sullivan County a bit upstate, and these scenes are thoroughly rural—and maybe a bit cold. Monitors may at a given moment close in a red flower or pale stone, while one last monitor stands unused off to the side, like a deathly tribute to dated technology and her career. A gathering seems in progress, with younger guests, but without obvious signs of celebration. Lucier herself presides over all, with one monitor for her face alone. I hesitate to call it smiling.

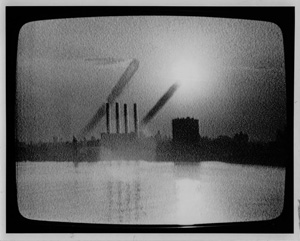

The scenery includes a building at a precarious angle, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa for ordinary upstaters. It seems too grand for a shed and too modest for a home, but there it is, on the far side of a pond. If it is gray and falling apart, such is aging, but then she has always been aware of damage and decay. Dawn Burn from 1975 (also in "September 11" in 2011 at MoMA PS1) turned the camera on the sun, burning out its eye just as staring at the sun is blinding to humans. The images in Leaving Earth include burning branches. It is hard to say how much their fire brings warmth.

Lucier ticks off the lasting cost of damage and decay. Her husband, Robert Berlind, left this earth in 2015, and journals from his last illness supply the on-screen text. It too matter of fact to call it poetry, lamentation, confessions, or epigrams, but terse and telling all the same. A painter, he neither runs through his life nor dwells on impending death. Yet the words slip among all tenses, past, present, and future.

Images accumulate, like an unfolding portrait or a determined record, but they never quite cohere. The arbitrary can be deeply flawed, disrupting the immersion and lessening the art as for Smith. Lucier, though, has always been adding things up and taking them apart. If she loves her memories, it is with critical detachment. The words still speak, and the flames still burn, but they cannot exhaust experience. If she is left forever alone on earth, it is because there is nowhere else to go.

The poetry of LA

Cauleen Smith could have even a New Yorker nostalgic for Southern California. That may sound like a tall order, although the sensation may last all of fifteen minutes, but Smith will make you feel right at home. She sets out plush sofas—so comfortable that you may get up only to be sure that you have caught all four of the installation's projections. Throw rugs can hardly cover the upscale Tribeca gallery, but then what could? Besides, you know what people say: everyone out there is famous for fifteen minutes.

That includes Wanda Coleman, and Smith, who appeared in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, is out to extend the late poet's moments of fame. The filmmaker is nostalgic not just for the city of her childhood, to which she has at long last returned, but also for a black woman who loved music almost as much as words. This is The Wanda Coleman Songbook, and you get to play DJ. You will just have to trust the gallery that Coleman, who died in 2013, earned a reputation as the poet laureate of Los Angeles. Her name may not mean much to a New Yorker, but then neither might this view of the great city without a city. This is LA as itself poetry but oddly remote from life.

That includes Wanda Coleman, and Smith, who appeared in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, is out to extend the late poet's moments of fame. The filmmaker is nostalgic not just for the city of her childhood, to which she has at long last returned, but also for a black woman who loved music almost as much as words. This is The Wanda Coleman Songbook, and you get to play DJ. You will just have to trust the gallery that Coleman, who died in 2013, earned a reputation as the poet laureate of Los Angeles. Her name may not mean much to a New Yorker, but then neither might this view of the great city without a city. This is LA as itself poetry but oddly remote from life.

Smith, who is African American, does not quite efface the urban core that many blacks call home, but she does relax and enjoy it. She treats the film's multiple channels as an immersive experience. Two projections cover the facing long walls, the other two the alcoves to either side. Besides the sofas and rugs, she includes a coffee table for Coleman's books and a quaint countertop with a good old turntable, where the songbook in question plays along. Smith commissioned music for the five tracks of an EP. Now she invites visitors to place the needle and to listen.

An EP may seem like a letdown or a rarity for those nostalgic for LPs, but this one is itself art. It comes in pink vinyl with splotches of bright red. I am tempted to say blood red, but in the installation's spirit it might be better to think of candy canes and melted strawberry ice cream. Coleman also went by the name LA Blueswoman, but only some of the tracks are bluesy. All are as close to background music as the projection. It could be a direct retort to the California of Ed Ruscha.

Where Ruscha goes heavy on irony and detachment, Smith is sincere and totally involved. Where he photographed Every Building on the Sunset Strip, she is seemingly random but also selective. She cuts among sunsets, palms, utility poles and a railroad crossing, where she waits like anyone else for a train to pass before she can move on. The building on the far side has its share of graffiti, but she does not see it as defacement. Even the region's bane, traffic, looks charming from overhead on a highway at night. Segments may rush past, but they feel slower and longer, like those proverbial fifteen minutes of fame. Poverty and luxury alike are nowhere in sight.

So much else is surely missing, not least the poetry. Coleman's words appear on-screen now and then, but difficult to read, and aloud on vinyl, but just as difficult to hear. Is there a dark side? Three cut-outs leave their silhouettes on the walls, as more utilities and a creepy mask. Still, in a fourth projection, outstretched fingers like an ILY (I Love You) sign spell LA. As you head off to the gallery scene, downtown restaurants, and an overcrowded Canal Street, that sign-off, too, will soon be gone.

A mind of its own

You may have heard this story before—and not just online. When Leonardo da Vinci painted an angel for Andrea del Verrocchio in 1475, the master, it is said, was so awed that he never painted again. To less romantic scholars, it was merely what would have been impossible before the Renaissance and medieval money, a business decision. Verrocchio had a demand to meet for both painting and sculpture, so why not specialize? It is only fitting that AI most often makes the business section of The New York Times today. But could the label conceivably apply to Cohen starting fifty years ago?

Regardless, his show makes a flashy first impression. It devotes an entire wall for what could equally well be video art or a painting's coming to be. At any given moment, it is a work in progress, and Cohen considers his task an examination of an artist's cognitive processes. Others might put software on a diet of Web sites, with every new work filling in the blanks. That could leave instructions to such generalities as a painting about X in the style of Y. The British-born artist would rather take things step by step.

That big mural really moves. If AARON does have a mind of its own, it thinks fast. It lays out one shape after another and on top of another, for an increasingly dense landscape of truly wild flowers, before starting again. Color fills the black outlines as quickly as they appear. When it comes to actual canvas, too, Cohen's strength lies in those layers. Subjects include still life and figures akin to portraits, with a woman behind a flower pot, for a compressed space within a deeper world.

Modernism was always about space and its perception, and his early work picks up on Paul Cézanne and his bathers. It sets bathers within that denser, wilder landscape. AARON may not realize them as individuals, and what look portraits might be studies in the very idea of introspection. Eyes cast downward, and a hand raised to lips might hold a cigarette or serve as a shield. Cohen, in turn, gains over time from a return to basics in the software itself. Sketches reduce figures to jointed lines, like machines.

Their style may look more appropriate for advertising or nursery school than for art, much as I enjoyed that video mural. Even there, software has it limits, although human art can be formulaic enough, too. If AI from Refik Anadol amounts to visual elevator music, its successor in MoMA's lobby, by Leslie Thornton, has its own soothing swirls. For all the hype, does any of this add up to intelligence? Stendahl quipped that God's only excuse is that he does not exist, and one might say the same of AI.

For all that, AARON's landscapes have an appealing density, figures and still life an appealing simplicity. Cohen's premise is more interesting still. The Whitney considers the canvases the art and the video a look behind the scenes to their creation, and it gives equal weight to both. It has only a handful of paintings, from the museum collection, the video, and two plotters that Cohen designed himself. There have to be two, because software can turn out any number of multiples from the same instructions, as theme and variations. One might think of AI as more an aspiration than a fact, but one can always hope.

Mary Lucier ran at Cristin Tierney through March 2, 2024, Julian Charrière at Sean Kelly also through March 2, Cauleen Smith at David Zwirner in Tribeca through March 16, and Harold Cohen and AARON at The Whitney Museum of American Art through May 19.