9/11: Before and After

John Haberin New York City

September 11 at MoMA PS1

"September 11" opened on the tenth anniversary of the fall of the Twin Towers, but something does not appear in its name. That is not a matter of style. The show's entrance wall speaks plainly enough of "9/11" and "the attacks," but the title makes a statement, too. This is not simply the art of 9/11, it says. It is about presences and absences in the memory of others.

Out of the picture

"9/11," the entrance wall observes, "was the most pictured disaster in history," and "September 11" refuses to picture it. For that matter, PS1 refuses to describe it. It takes for granted that you will know why it quotes E. B. White on "mortality," "New York," and "the sounds of the jets overhead." The show has art about all those things—but much of it from before 2001, like White writing in 1948. It includes exactly one work made as a response to 9/11, and even that work "obscured the site." Ellsworth Kelly stuck a green paper trapezoid on a map, to imagine Ground Zero left forever as grass.

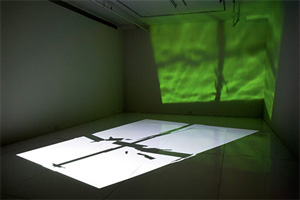

The show's spareness goes with its silence. The curator, Peter Elley, chose barely forty artists, most with a single work and practically all on just half the second floor. The floor's other wing recreates an English cathedral, for a Renaissance choral work by Thomas Tallis. Janet Cardiff introduced her sound art in her PS1 retrospective one month after 9/11, and it has never sounded better (although it promises to return to the Cloisters in 2013, as true church music). One enters the ellipse of forty speakers to find one's place of immersion or repose. Already, one can ponder what else one has left behind.

None of the rooms feels crowded, and few nearby works comment on one another. Jane Freilicher's window onto a city hangs across from the view from Mary Lucier across the East River, on seven monitors as in some unstated ritual. Freilicher's view centers on a gap in the skyline, to add light and depth to her still life in the foreground, but one can imagine that something has fallen. Lucier records the arc of sunrise as what she calls a "scar," and one may remember instead a dark billow of smoke on 9/11. The only two works in Arabic also share a room, one of them by Siah Armajani in ink on gesso as Prayer. One wants the text, of Sufi poems, to come together as an image, and it refuses.

Just as often, work by the same artist hangs apart. One room has Christo on his arrival in New York, proposing to wrap tall buildings, and Alex Katz with his ripples on water, in the Pop portraitist's rare approach to abstraction. The adjacent room has Katz's corresponding twilight and Christo's actual wrapping of something long and mysterious in red tarp. One can recall ten in the morning as one minute after the south tower's collapse, the pair as a passage into darkness—or into light. One can see the wrapping as sustaining buildings or the building's absence, and one can see the tarp on the floor as a dead body or a construction site. That, however, is up to you.

The show's most overt juxtaposition occupies the central room. A seated woman by George Segal faces Roger Hiorns's thick carpeting of dust from an airplane fuselage. She also faces Harold Mendez's two white paintings—or rather the ground of paintings scraped and beaten. Mendez calls one Nothing Prevents Anything. It is hard not to see these as a single installation, and The Patriot by John Williams plays softly in the background. It is also hard not to want to share the woman's bowed head and park bench.

Is all this mere curatorial arrogance? Is it fair to 9/11 or, even more, to the artists? Leave aside those who dismiss an author's or artist's intentions, from T. S. Eliot to W. K. Wimsatt's "intentional fallacy" to the "death of the author" for Roland Barthes. Leave aside a postmodern love for "citationality," or quotes within quotes. What happens when a show called "September 11" rips art and events out of context, like Maurizio Cattelan when he installs a gold toilet in the Guggenheim or suspends his tribute to 9/11 from a museum's dome? What if it leaves out of the picture not just 9/11, but much about the art?

Degrees of prescience

Actually, a lot happens, in a moving and memorable show. The curator must have dreaded yet another display of "art after 9/11," "The American Effect," or film of that day and its aftermath by Laura Poitras, and so did I. The airplane dust lingers in memory long after Xu Bing's 2004 dust collected from downtown and displayed elsewhere, inscribed with a Zen poem that imposes on events that much more. ("As there is nothing from the first / Where does the dust collect?" Get out your vacuum cleaner, fast.) At PS1 the sheer range of associations with 9/11 testifies to its impact, even without a mention of Sue Coe.

MoMA has done some serious damage in absorbing PS1, but this once it takes advantage of a place apart. It left the spotlight that morning on Ground Zero, especially with a museum that opens at noon. It offers a true "before and after" picture—how art looks different after 9/11 and, in turn, how 9/11 looks different after art. And, if art and 9/11 do not look different, one can better ask what has changed. As the entrance wall also observes, the relentless imagery "has been used to justify political, security, and military decisions worldwide." As a flag by Barbara Kruger asks, "who prays loudest," "who dies first" and "who is healed"?

Art gets the honor of prescience, like Sarah Charlesworth in her grainy 1980 photograph of a woman falling from a hotel. Twisted automobile parts for John Chamberlain become wreckage again, especially when they rise like twin towers. William Eggleston photographs a hand in an airplane, stirring a glass—their fate newly in doubt. Feminism and patriotism vie for Rosemarie Trockel in her tapestry woven from or unraveling into spools of red, white, and blue. Fiona Banner's black pennants hang above the main hall, and black borders convert a stack of paper by Félix González-Torres into the anonymity of death. One may welcome the silences.

So often here, New York is the principal actor, much as so often for Isa Genzken. It is the newspaper blown down a street for Diane Arbus. It is the mournful debris of a ticker-tape parade the year before 9/11, in Little Flags, a film by Jem Cohen. It is the slivers of skyscrapers in a video collage by Gordon Matta-Clark. John Pilson's photos of the graveyard shift at World Financial Center become images of evacuation, from the hand draped over a cubicle to endless reflections in bathroom mirrors. Remarkably, an airplane looms somewhere outside.

Generally, the most literal commentary fares the worst. I do not know why Ellsworth Kelly alone made the cut for a response to 9/11, but his green trapezoid says more about his painting than about Ground Zero. Only Susan Hiller speaks directly of time and memory, in Victorian memorial plaques accompanied by an audio lecture on human needs—and one may want to interrupt to get back to reality. Still, Lara Favoretto can refer to "if you see something, say something" with a black suitcase, because it seems so abandoned and alone. So does the forgery that gave a pretext to the Iraq war, in a cardboard model and its photography by Thomas Demand. But then, after the first Gulf war, Mark Lombardi already charted the nexus of banking and government that armed Iraq.

If "September 11" has an ending, it comes in 1963. In the layout's one dead end, Bruce Conner plays live audio coverage above film of President Kennedy's Dallas motorcade, clips of Kennedy's life, and a collage of his times. With the gunshot, the screen dissolves into jagged white. I could have done without "war is over if you want it" from John Lennon and Yoko Ono, but together they have "A Day in the Life" repeating over and over in my head. Another generation had its attack with perhaps a longer shadow. Another generation had its moment of silence after 9/11.

Silence on 9/11

This page was silent on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, even with the opening of the National September 11 Memorial—and so perhaps were you. One remembers a clamor of voices, from Bush with his bullhorn to war cries and tabloid "portraits of hope." One may forget how slowly they and others came to speak at all. Artists, too, hardly knew what to say, and people were less than sure that they wanted to hear it. When Thomas Hirschhorn addresses terrorism, I was not so sure that I hear much of anything at all.

When I wrote about art after 9/11 back in 2004, I had to face whether it was even possible. Roger Kimball, for one, had said no—not because 9/11 was sacred, but because art was. Of course, he had just found an excuse to complain again about "political correctness," the usual attack on culture in the guise of defending it. But he was hardly alone, even as the burden of defense shifted to art. When The Daily News denounced a proposed Freedom Center with a museum, it called a drawing by Amy Wilson un-American—but also too close and too soon. In a panel on "Art That Makes Headlines," I had to insist that art has often weathered a public outcry.

When I wrote about art after 9/11 back in 2004, I had to face whether it was even possible. Roger Kimball, for one, had said no—not because 9/11 was sacred, but because art was. Of course, he had just found an excuse to complain again about "political correctness," the usual attack on culture in the guise of defending it. But he was hardly alone, even as the burden of defense shifted to art. When The Daily News denounced a proposed Freedom Center with a museum, it called a drawing by Amy Wilson un-American—but also too close and too soon. In a panel on "Art That Makes Headlines," I had to insist that art has often weathered a public outcry.

Wilson was drawing on her own uncertainty and silence. Her thought balloons quoted others, from the newspapers and from both sides of the story. They also concerned Abu Ghraib, not Lower Manhattan, and a surge of political art soon after meant mostly art about war, as for Nabil Kanso. One can see why, when America itself had slid so quickly and unforgivably from Al Qaeda to Iraq. War also gave artists like Hans Haacke something to say. After all, even classic history paintings needed something to celebrate or to attack.

Neither one has come easily to Lower Manhattan. 9/11 changed "everything," but exactly what? In part, the day came to stand for a loss of control over a larger world, even as it led to more wars further from home. Still, that fate dates at least to the Vietnam War—which helps explain why Ground Zero now has a wall of inscribed names, just like the Vietnam War Memorial by Maya Lin. Not even the rush to find heroes could erase the loss. The falling shadows by Paul Chan find a singular beauty in helplessness.

What, then, to commemorate or to remember? Pearl Harbor galvanized the country, which allowed the country to focus on much more than Pearl Harbor. The Holocaust stands as an unthinkable crime against the Jews and, by that very fact, against humanity. The Vietnam War Memorial succeeds by finding common ground after deep political divisions, in the soldiers who fought and died—while the memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr., in Washington tries to bury the divisions amid pharaonic splendor. Here peace, focus, and humanity do not come easily, and physical reconstruction has dragged on and on. Will the memorial change that? Already it has started an argument over whom to include.

On the one hand, that clear September morning belongs to everyone, and you, too, probably remember the moment as if it were very much your own. On the other hand, a senseless attack by a handful of extremists struck exactly once, and the "war on terror" has claimed no lives at home since. A choice between a universal and a particular has a way of excluding almost everyone, and the unveiling of the National September 11 Memorial ended up inviting only those with a very personal loss. Students at first could not even hold their own vigil at Stuyvesant High School, a few blocks away. The good news is that ambiguity between the personal and the political empowers art. It empowers "September 11," and it empowers a national memorial as well.

"September 11" ran at MoMA PS1 through January 9, 2012, but Janet Cardiff's "The Forty Part Motet" remains on long-term view. Xu Bing exhibited on 5 West 22nd Street through October 9, 2011, as part of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council's InSite program of events in commemoration of 9/11. A related article looks at the National September 11 Memorial.