Photography as Agency

John Haberin New York City

Magnum Photos and Robert Capa

When the founding members of Magnum Photos raised a toast in 1947, they knew that they were making history. They had founded a photo agency as a collective, giving the photographers agency in every sense of the word. They even divided the world among them, with three to pursue their vision in Asia, Africa and the Middle East, and Europe and the Americas while the fourth could roam at will.

They thought that they were creating a global history as photographers as well. Three had followed troops into combat in World War II, and the fourth had photographed prisoners of war. Now, over (naturally) a magnum of champagne, they saw themselves as harbingers of a lasting peace. With "Magnum Manifesto," the International Center of Photography takes stock of both histories—that of Magnum Photos and that of the world. It finds members (ninety-two at last count) still in pursuit of political change, but they had a faith in themselves as global citizens or at the center of photography largely gone. A return to ICP for a second show, of Robert Capa in Spain, shows just how strong that faith was.

Capa and Gerda Taro arrived in late 1936, only months into a bloody civil war. Ordinary men were kissing wives and children goodbye to enlist in the fight against fascism. Women joined them at the front line and stayed behind to manage materials in defense of the republic. Eighty years later, Magnum still invites new members, with a screening process that takes years. And its archives continue to grow, feeding a database of more than half a million items. This, though, was journalism as a call to understand.

Capa photographed those last moments of intimacy and men waving from the troop train for that one last goodbye. He captured their optimism, their intimacy, and their pride. Taro preferred faces, in direct encounters closer to portraits than photojournalism. They could not know that they were seeing death in the making. Not three years later, with Taro dead and the smiles all but gone, their work and the course of war became a book, as Death in the Making. Yet their photos, chiefly his, belong to a time when nothing could nothing could entirely dash their hopes.

An anachronism?

A packed opening wall for "Magnum Manifesto" holds some of the most memorable images of photography's last century. There they are, a dogged troop of refugees like an inexorable human wave, an Indian mother and child pleading for relief from famine, an assertion of international law under the American flag at Buchenwald, a lone Vietnam war protestor on the Washington Mall, and a black power salute at the Olympics in Mexico City. They play out against text from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948 in Paris, but with none of its certainty that justice will apply to all. Rather, they already attest to the turmoil of the 1960s. They also see that turmoil in human terms, as essential to photography's claim to truth. That war protestor holds a flower just inches away from the massed bayonets of the National Guard.

They present Magnum as greater than the sum of its parts. Labels appear only around the corner, making it by no means easy to assign credit. (For the record, I have mentioned photographs by Robert Capa, Werner Bischof, Chim, Marc Riboud, and Raymond Depardon.) Beyond them lie extended projects by a single photographer—such as migrant workers for Eve Arnold and family portraits by Elliott Erwitt. Each of the show's main sections has the same mix of opening overview, with text, and individual concentrations. Together, they describe Magnum Photos as both collective and agency.

Capa had come up with the idea, and George Rodger, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Chim joined him in the cafeteria at MoMA for that champagne toast. (David Seymour took his nickname from Szymin, his family name back in Poland.) In returning to that moment, ICP is recovering its own history as well. Cornell Capa, another Magnum photographer and Robert's brother, founded it in 1974 with much the same dream of socially concerned photography. That concern guided two shows at ICP, but "Public, Private, Secret" and "Perpetual Revolution" were heavy on new media, as if photography could no longer keep up with the times. Now it gets back to basics.

But not entirely. Out in the lobby, a photo collage plays continually on two walls and a touch screen, as Unwavering Vision. For its second installation, Alan Govenar, Jean-Michel Sanchez, and Julien Roger have added a filter to bring it down to the nearly fifteen hundred Magnum photos in ICP's collection. It is interactive as well. One can drag one's finger to any point on a time line. Selecting a photo brings up related images and reconfigures the time line.

Inside, the show has its multimedia, too, even before the International Center of Photography pulls a media lab into a new home in 2020. It divides chronologically into three parts, with "interludes" between parts. One interlude restores a much earlier form of interactivity, with a slot machine. For "America in Crisis," a 1969 show at the Riverside Museum, Charles Harbutt created Picture Bandit. A pull on the one-armed bandit changes the portrait of a divided America on the walls, and you may not like what you see. In a crisis, you take your chances.

The second interlude allows members their outside interests. On several monitors, hands turn the pages of books of photography. Photos recover their context in corporate reports. Companies commissioned them to earn sympathy for their social awareness, and the photographers had a stake in both the commission and the awareness. The show ends with one last video collage—photographs broken by testimonials to what Magnum means today. It may be as central as "an expression of feelings" and "a way to behave," as limited as a gathering of overwhelmingly white men, or "an anachronism" with overtones of both.

A collage of individuals

The entire show, then, comes as a succession of photo collages, on video and physically on the walls. Even the concentrations on a single artist have their collage elements—clippings from the publications in which they first appeared. Photographs of prisoners in Texas by Danny Lyon ran under the headline "Our Prisons Are Criminal." Like the wall text opening each of the show's segments, they describe photography as a series of "Magnum manifestos." They are also changing manifestos, as iconic images give way to more intimate encounters in a diverse and troubled world. Then again, Cartier-Bresson hated the label photojournalist all along.

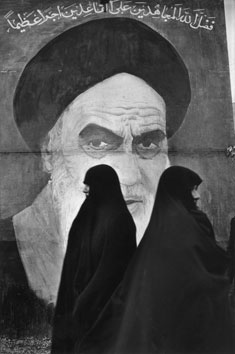

After the first segment, "Human Rights and Wrongs," the exhibition continues past 1968 to "An Inventory of Differences." The politically correct title notwithstanding, it attests to a world fragmented into black and white, cultures and subcultures, guards and prisoners (the subject of "Marking Time" at MoMA PS1). No inventory can conceivably be politically neutral. The final segment takes up the years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, as "Stories of Endings." Here fresh hopes give way to terrorism, the Taliban, war in Eastern Europe, and the refugee crisis that Don McCullin might have recorded elsewhere. Traditional photography gives way, too, to larger formats, digital prints, and color.

Magnum, the show insists, is still on the front lines, but who is drawing the lines? To answer, one might have to ask what counts as a beginning or an ending. One may question even the show's tale of origins. The toast was real, but Rodgers (in one account) learned of Magnum's founding only when he discovered that he was already a member. The tale also skips right over a fifth founding member, William Vandivert, and the agency's first co-presidents, Rita Vandivert and Maria Eisner. No wonder the photographers in the concluding video cannot agree on Magnum's meaning or relevance.

The curators, Clément Chéroux of SF MoMA with Clara Bouveresse and Pauline Vermare, acknowledge the tensions. Their unusual layout also does more than you might think to acknowledge the photographers. It includes seventy-five of them, with hundreds of photographs and documents, but fewer than thirty projects. That way, one can linger over walls, manifestos, and personal approaches. That way, too, one can appreciate the encounters between artistry and photojournalism. A peeling poster of the queen becomes the visual equivalent of the crumbling of a colonial empire in Ceylon for Martin Parr.

In each case, the photographers see events through individuals, like Eugene Richards or Dan and Sandra Weiner in a vintage New York. That can mean marginalized individuals, like "hermits and mystics" for Alec Soth, strippers for Susan Meiselas, addicts and hookers for Jim Goldberg, occult practices in Spain for Cristina García Rodero, or a masquerade for Inge Morath—but not necessarily. When Paul Fusco follows Robert F. Kennedy's funeral train and Peter Marlow the last SST, they turn their camera on those watching from the sidelines. When Richard Kalvar follows a campaign for Senate, he takes it one handshake at a time. When Alessandra Sanguinetti probes terrorism, she looks to its aftermath in the faces of others. One woman holds up a sign to address the terrorists themselves, as je ne te juge pas ("I do not judge you").

Individuals appear even in their absence. Donovan Wylie sees Maze prison in Northern Ireland as sunlit windows, loose curtains, and empty beds. An empty table serves Erich Hartmann for "Our Daily Bread." They appear all the more haunted when they try hardest to exert their presence. Gypsy children raise their painfully gaunt biceps for Joseph Koudelka. They are not mere stage performers or anthropological specimens, like disaster areas for photo spreads in today's New York Times, but they could almost be raising a toast.

The face of defeat

You may know the Spanish Civil War as a trial run for fascist aggression, and German bombs did much to deliver victory to Francisco Franco's dictatorship. You may know it from the poignancy of courage without illusions in Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls. You may know it, too, from the left's loss of belief in Communism, as the Soviet Union refused to engage. The International Center of Photography sees first and foremost a landmark in photojournalism. Capa (whose brother, Cornell Capa, in fact founded ICP) shares the galleries with twelve contemporary women from Magnum, as "Close Enough." ICP sees, too, a foretaste of "the threat to democratic norms" today.

The media now might look back on Capa's men eager for combat as in denial—and Capa himself as sentimental. And no question that he knew which side he was on. He never shows combat, and Nationalists hardly appear at all. Still, he dedicated himself to what he must have seen as the facts, without exaggeration. The military had staged the July coup, but this was the People's Army, on behalf of what it called the New Spain. These, too, were bottles of milk and steel jars of magnesium, a metal at the heart of a region's economy, when a journalist now might find them too boring for words.

The media now might look back on Capa's men eager for combat as in denial—and Capa himself as sentimental. And no question that he knew which side he was on. He never shows combat, and Nationalists hardly appear at all. Still, he dedicated himself to what he must have seen as the facts, without exaggeration. The military had staged the July coup, but this was the People's Army, on behalf of what it called the New Spain. These, too, were bottles of milk and steel jars of magnesium, a metal at the heart of a region's economy, when a journalist now might find them too boring for words.

Then, too, Capa shunned the worst cliché of all. The real sentimentalism sees heroism and triumph in the face of ruin, so no wonder it piles on the ruin. It cannot face up to lost lives, with survivors carrying on as best they can. His unbearably young soldiers and civilians are not heroes but just people. Their vulnerability shows in their faces and gestures quite as much as their hopes.

Heroes can stand alone, but these people enlist in groups, act in groups, and suffer in groups. They act in concert because there was a job to be done. Men hold up a painting from a church, so that a woman can take its inventory. If a reminder of the program to preserve Spain's heritage glorifies them, so be it. They are who they are. If the photos seem uncomposed, shadows cut across the smiles from the very start, and many have become iconic because of that shadow.

Nor can Capa turn his back on defeat, and defeat places that early optimism in a troubling new light. That willingness to die looks darker after so many deaths. He also returns to earlier motifs to bring out the changes. People straining at a gate to participate in war become people at the gates of a morgue. An early body at rest may look dead when a corpse looks so alive. Planes circling overhead might pass for crows circling the dead.

The curator, Cynthia Young, fills in the story of the book, from publication in Paris to a version in New York of poorer quality. An exhibition at the New School did better. Like Taro, David "Chim" Seymour contributed a dozen or so photos, but uncredited. ICP credits the book's designer, its text author, and André Kertész, a fellow photographer who encouraged Capa, as well. In any event, Capa was halfway around the world when the book appeared. For him photojournalism, like any good cause, must carry on.

"Magnum Manifesto" ran at the International Center of Photography through September 3, 2017, Robert Capa through January 9, 2023.