Staging the Last Century

John Haberin New York City

Photography's Last Century and Madame d'Ora

When "Photography's Last Century" opens with Gregory Crewdson, you just know: this will be a century of staged photography. Only wait, for there is more at the Met than stage sets and actors.

There is more, too, to photography's last century that a private collection like this one cannot touch. Otherwise, in fact, why look to a collector for themes, taste, and insight? To complicate matters, Madame d'Ora had her own reasons for staging her subjects at the Neue Galerie. Rather than feeling held back as an artist by fashion photography, she thrived on its artistry—and it took the horrors of the last century to oblige her to drop the poses.

Mystery theater

Even if you do not know Gregory Crewdson by reputation, you will know the look of a film still, from its large scale and living color to the woman alone. The photographer has placed her there, in the sunken bedroom of a split-level ranch home and in the aftermath of goodness knows what. A bed does not come littered with plants, the same plants that she nurses in her hands. She seems to look to them for answers that she will never hear. Not everyone at the Met is literally on stage, but they all want to be seen, like dancers at El Morocco for Garry Winogrand. Tables there were not so easy to come by in 1955, and they marked you as an insider or a star.

Photography has a rich history of posing for the camera, from well before nudes by Edward Weston to well after Cindy Sherman. And the collection, a promised gift from Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas J. Lee, has them both. Still, Weston does not just chose his sitter, but also cuts off her body parts to the point of abstraction. When Hiroshi Sugimoto photographs an actual theater, he opens the shutter for the length of the movie—so that the quaint architecture has its own drama and the screen becomes white. Robert Frank uses a long exposure, too, to sink a railroad crossing in darkness even as a single light flares out like an explosion. They are staging not the action but the photograph itself.

Staged can mean hokey, with an obvious agenda, but also drama for its own sake and its mystery. And this is one strange history of photography. Its mystery theater includes rippled light and dark on an irregular cobblestone street for Brassaï in Paris, clothing hanging from trees for Robert Gober, and a car wreck sinking into a river for Arnold Odermatt in Switzerland. Crewdson's woman is caught between youth and age—and between unstated external events and private terrors. Diane Arbus has her strange encounters, as with frowzy women at an automat or identical twins dressed seemingly for mourning. Vik Muniz opens a frail birdcage, and who knows what has flown out and where it has gone?

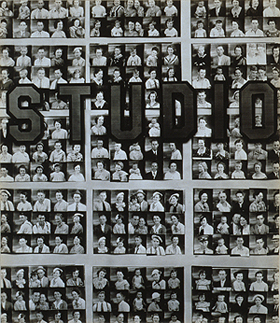

Much of the strangeness, too, lies in unfamiliar choices. The twins and Sherman's Untitled Film Stills are icons, and so are Andy Warhol at the Factory for Richard Avedon, a little doll in a lonely interior for Laurie Simmons, or a studio window for Walker Evans. Yet Avedon also had a detour to Sicily, where a squat boy beneath an even squatter tree looks right out of Alfred Hitchcock. Simmons also photographed four women (Sherman among them) in choreographed swimming, and Evans also photographed his shadow. Robert Mapplethorpe turns up with not artists and the AIDs crisis, but an aircraft carrier on the Coral Sea, where the gray sea itself seems to have engulfed it—and Catherine Opie with not an excess of female flesh, but high-school football, albeit with much the same threat of body contact. Years before her Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Nan Goldin caught a woman in Boston Garden, already woeful but glamorous.

Others may come as surprise, period. Joseph Cornell, it turns out, briefly tried his hand at photography outside the box—and so did Sigmar Polke, manipulating the image to the point of illegibility. Along with her color paintings of black women, Mickalene Thomas and Nellie Mae Rowe aimed for the same glam patterning in photography in black and white. Rachel Whiteread recorded her resin cast of a water tower, looking even spookier. The show has a goodly number of familiar women, also including Zanele Muholi from South Africa, but it wants to make the case for more. Bunny Yeager, it argues, anticipates Sherman, and Florence Henri deserves to come out from the shadow of László Moholy-Nagy. It argues, too, for a portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz as a collaboration.

The curator, Jeff L. Rosenheim, ditches chronology—ostensibly for themes, but in practice so that each work carries its own strangeness. That studio window in Savanna hangs close enough to a shop window from Eugène Atget, but still several works away. Wispy figures close to ink stains by Robert Heinecken and Ralph Eugene Meatyard resonate with one another, but rooms apart. So do images of screaming by Sherman, Sturtevant, Lyle Ashton Harris, in orgasm of in horror. Wall text reads like essays on individual photographers rather than on the medium's history or nature. It may yet have in common its strangeness.

From fashion to horror

Dora Kallmus was hardly the last to ditch fashion for portraiture—or for portraits of horror. Photographers, too, have to earn a living, like David Seidner in fashion photography, and then, perhaps, they move on. Kallmus, though, had stuck to her trade for nearly forty years, and she was not out to repudiate her past. If anything, she had rediscovered it, as a Jew forced into hiding during World War II. She was merely caught up in changing markets and traumatic events. Just as much, she was reinventing herself and her subject, not for the first time, as a modern woman.

She thought first of fashioning fashion herself, before buying a camera on a trip to the Riviera at age twenty-three. And her sense of design informed her work from the start. She could linger over shoes or the hem of an elaborate skirt, and she often took charge of a subject's clothing and accessories. She also earned a reputation for talking to her models to set them at ease, eventually capturing them when they hardly thought to pose. Just as much, too, she knew the importance of image enough to style herself Madame d'Ora. She was the first woman in Vienna to have a photography studio, and it took off.

Born to a prosperous family in 1881, she also had access to artistic circles, and she valued them as much as fashion. She photographed artists, playwrights, performers, and musicians, including Alma Mahler and Arthur Schnitzler, with the same care for poses and gestures as in her commercial work. Alban Berg looks brash and young, with one hand to his cheek and another to his side, while Gustave Klimt fingers his beard. If even a countess or two values her independence, serving in the Red Cross in World War I, d'Ora shows them in uniform. She also photographs herself—often and always with her cat. She can seem old or young, ugly or attractive, in the course of less than a year.

Born to a prosperous family in 1881, she also had access to artistic circles, and she valued them as much as fashion. She photographed artists, playwrights, performers, and musicians, including Alma Mahler and Arthur Schnitzler, with the same care for poses and gestures as in her commercial work. Alban Berg looks brash and young, with one hand to his cheek and another to his side, while Gustave Klimt fingers his beard. If even a countess or two values her independence, serving in the Red Cross in World War I, d'Ora shows them in uniform. She also photographs herself—often and always with her cat. She can seem old or young, ugly or attractive, in the course of less than a year.

She had already had work in Vanity Fair and The Tattler when she moved to Paris in 1925, where she collaborated with more noted designers and milliners. As in fin de siècle Vienna before it, the very notion of modernity was changing, and d'Ora had no trouble keeping up. She preferred softly textured backgrounds and increasingly over-the-top poses. Icons like Josephine Baker, the black actress and activist, and Maurice Chevalier seem straight out of modern dance. She shifts again in time to close-ups and an increasing restraint. She is redefining the modern woman as beautiful enough but also something more.

You may not associate Austrian or German Expressionism with the comforts of fashion rather than "degenerate art"—for all the cosmopolitan eye of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or the glitter, fabric, and femininity in Klimt. When Max Beckmann attends to his clothing, it is to preen as a snobbish bourgeois while mocking the bourgeoisie. Beckmann also reflects on the toll of war, but then so does d'Ora. Back in Paris and Austria from southeast France, she photographs refugees more displaced and at risk than herself. A mother seems too much in the shadow and the children in her arms far too much in the light. d'Ora also photographs a slaughterhouse, knowing full well that she and the refugees had barely evaded slaughter.

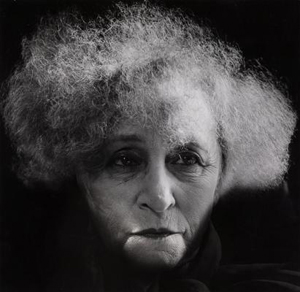

She tries her hand at color, to bring out the blood and guts, but a cow's severed legs and head look more than lurid enough in black and white. Fashion commissions were not to be had in this postwar economy, unless one thinks of a lamb's pelt as yet more of fabric and surfaces, so d'Ora returns to portraits as well. Jacques Tati, the director and silent comedian, must hide in a corner, too, if also with his cat. Other portraits again rediscover women as autonomous and aging, like Colette, the writer, in strong contrast, pressing her wrinkled face to the picture plane. Still, d'Ora can also revisit Chevalier and bring all her subjects into the present. Pablo Picasso has never had a franker and broader smile.

"Photography's Last Century" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through November 30, 2020, Madame d'Ora at the Neue Galerie through January 4, 2021.