A Scream at Gunpoint

John Haberin New York City

Edvard Munch and The Unfinished Print

Only days ago, an artist consumed with terror and desire became the victim of armed robbery. Edvard Munch would have appreciated the irony.

The scene(s) of the crime

The thieves carried off two of his best-known works, The Scream and a Madonna. They grabbed them right off the wall, at gunpoint, defying both security guards and panicked museum visitors. Munch might have loved that the crime took place in broad daylight but under artificial light, as if to heighten and distort Oslo's painfully long summer days.  The harsh northern climate always inspired him, even as his figures cower in dark corners of ill-defined rooms and his open skies hover unsettlingly between day and night.

The harsh northern climate always inspired him, even as his figures cower in dark corners of ill-defined rooms and his open skies hover unsettlingly between day and night.

He might have wondered, too, at the irony that the only scream came from his work, and no one will ever hear it. In The Voice, too, in Boston, the sun may leave a savage yellow pillar almost at dead center of the lake. Yet it never touches the boaters, unmoving in the background. It cannot penetrate the woods in the foreground, with the only possibility of leaves on all those tree trunks cut off at the top of the painting. The central figure—a woman wrapped in her white summer dress as stiffly as in a shroud, cannot open her mouth to speak in her own voice.

The criminals treated the works as brazenly and indifferently as they treated bystanders. Forget the cool, slick images of master criminals in the movies. Maybe art crimes seemed like that when a Vermeer vanished neatly from its place at the Gardner Museum years ago. This time, however, one remembers the photo in all the papers, of a man awkwardly lugging his prize out to the parking lot. The camera's distance makes the act seem smaller and clumsier, like moving day for the start of school next week.

The frames ended up in the trash, another reminder of the art object's reality and fragility. Art may sound eternal, and Munch may evoke an existential crisis. Munch's art, however, exists on canvas or paper, and his images live in the memories of people who may never quite know what to make of them—not unlike the thieves, perhaps, wondering how to unload their cargo now. Goodness knows how the media are holding up under the rolling, folding, and bundling.

With images this well known, one could almost overlook that the thieves did grab works on cardboard. The robbery took place at the Munch-museet, or Munch Museum. However, the National Gallery, also in Oslo, owns an arguably much more famous version of The Scream, which includes oil paint along with the tempera and pastel. It has the deep orange skies, blue waters, and dark shadows on the wooden bridge that I remember best. This, too, was stolen in the past decade, although subsequently recovered.

The fact of "mere" works on paper matters. Munch insistently works and reworks each idea. The Scream exists in two or three other versions as well, not to mention lithographs. Ironically, the copyright on photos of the National Gallery version has expired.

Crosses to bear

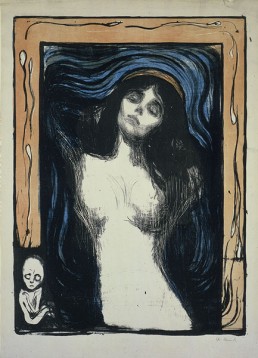

Munch left at least five versions of Madonna, too. The Frick showed several lithographs side by side this very summer—in a splendid exhibition of "The Unfinished Print." All of this should have one asking what one even means by unfinished, and the Frick does just that.

"The Unfinished Print"—it must evoke leftovers, works that made even the artist lose interest. At the same time, it may sound almost redundant. A print's scraggly or incisive lines may result from the mark of a stylus on wax or that odd-shaped tool, a burin, across a metal plate. Either way, they evoke a window into an artist's first thoughts, a drawing. So may the washes of ink on successive pressings that add color to so-called chiaroscuro woodcuts. What, then, is new about the unfinished print?

In a sense, a print is always unfinished. After the impression, the plate remains more or less intact, open to further impressions—or even further embellishment and harsh erasure, what scholars know as successive states. Then, too, abandoning a print sacrifices less income, encouraging an artist to bask in the strangeness of a white background setting off a starkly conceived central theme.

One could almost forget how strikingly these impulses behind an unfinished print differ, even contradict one another. As a reproducible medium always close at hand, prints have served as copies after the fact of painting, bringing them to larger audiences. They have served, too, as initial trials for an audience of one.

The Frick's show tries to encompass all of these, not to mention quick but helpful lessons in the differences between, say, etching and engraving. It also has a broader theme—how prints encouraged a concept of the artist as creative, impulsive individual, whose every thought mattered. The show has some classics along the way of that evolution, including selected states of Rembrandt prints on the Three Crosses and the Presentation of Christ (both also among Rembrandt prints in the Frick), as well as Giovanni Battista Piranesi in his darkening prisons, the last of these echoed recently in an artist's book.

Rembrandt's career, of course, exemplifies those themes. He evolved from confident star of the art market, with a lively studio, to an artist now out-of-fashion but weighted with a greater emotions and greater sense of responsibility for his own persona. Artists taking charge of prints after their work began with Mannerism, perhaps with Parmigianino, whom the Frick showed just before—and who will return again with his Antea. Now, though, the artist is achieving, abandoning, and rediscovering an image that may never become painting. The versions of the Presentation of Christ struggle particularly over the foreground, in one state eradicating a complex crowd scene entirely. It points at once to the modern ideas of the work as definer of its own space and the artist, like a rejected god, at a distance from his audience.

The Madonna of the coffee mug

In the end, like those selections, the Frick's exhibition may be too small to do any of its themes justice. One would be remiss, however, in not enjoying the role of connoisseur and the chance to piece them out on one's own. Try to piece them out, then, with Edvard Munch.

Munch is a tough case. I find him easy to love but harder to like. The air of profundity and deep symbolism comes a tad too close to Victorian poetry. The lack of interest in color, space, and form never quite fits into the march Impressionism to Cubism—which in fact is why he matters. A proper modernist would surely prefer the march. A proper postmodernist might instead prefer retro.

I can never get over the feeling that The Scream earns its place on coffee mugs, great as it is. I may enjoy the parodies of it even better. I used to have a Warner Brothers version on t-shirt. He was a savvy enough artist to have liked it, too, had he seen it. It would have shed light, for him, on his insignificance.

Fair enough, and the Madonna lithographs at the Frick make one see the problems clearly—but also ever so much more. The woman has a body devoid of stain, much less traditional modeling of flesh. Yet she sways sensually, wrapped in her dark hair and the artist's cutting lines. Her closed eyes belong to the passive images of women from time immemorial. The flat background that cuts off her arms makes her more passive still.

Is the passivity an invitation or a mark of victimization? Do the signs of flesh and repose belong to desire or to death? A simulated wood frame could stand for a coffin, and a bent form at left could stand for an aborted fetus, but he (or she) also connects to the black, wavy lines pale ovals along the frame. They could stand for wood grain, tears, or male sperm on the move. The rich brown and blue curves around the woman's head could stand for a halo, an enveloping male gaze, or an extension of her own sensuality.

Munch see his woman as Woman, with a capital W—and that means as Madonna, victim, and whore, just as for Jan Müller and Helen Verhoeven today. One would think that any male, much less any artist, who represents women this way has some serious problems, from sexism to plain silliness. And he does, and that, too, is why he matters.

Raw or reproducible?

The very frankness with which the image approaches a stereotype should make one think, and Munch is always after the alignment of feeling and thinking. His gritty technique and his play with a reproducible medium highlight the stereotype. The reworked states implicate the male artist's labor and desire in that same stereotype. Remarkably, this makes the image not just psychologically loaded but stunningly contemporary.

Pubic hair seems to have migrated to just under her breasts. The represented frame gives the space the same shallow vertical as Tracy Emin's beds. The fluid black curves within the frame could come from Cicely Brown, were they not as dewy-eyed as a male fantasy, and the black scratches look like Chloe Piene's tales of abuse. The Madonna's deadened eyes and empty flesh may reflect not a passive welcome to the active male viewer but the sheer toll of ever fighting back.

The scratchy shadows could also make one mistake a lithograph for pencil on paper—one unfinished medium for another. Unfinished means both raw and in progress, both more authentic and less unique, and the artist is modern enough to exploit both possibilities. He is effacing the whole distinction between fantasy and reproducibility, and the lithograph of The Scream, not at the Frick, does the same.

It sticks to black and white, with broad, wavy lines that suggest a woodcut. Munch no doubt appeals to folk art traditions in northern Europe, for all the slick modernity of a lithograph. No doubt, too, echoes of the clumsier lines and unyielding wood of the older medium heighten the emotion. However, they also make one reproducible medium the subject of another. They make the concept of mass reproduction into part of the work—and its illusion—almost as much as Roy Lichtenstein's Brushstrokes in Ben-Day dots or Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work with a squeegee.

Critics from Walter Benjamin to Rosalind E. Krauss have seen mass reproduction as an essential part of Modernism, and they see it as undermining myths of originality and the avant-garde. In practice, one can always compare states and recognize differences. In practice, far too many of the 1980s' players with reproducibility, even Cindy Sherman, became not self-effacing postmodernists but postmodern celebrities. In practice, too, modern art always thrived because it gets to have it both ways.

Munch's themes and variations represent a fixation on subject matter, worse even than James Ensor back then, but over time they become elements in a series with a life of its own. From Claude Monet in his pursuit of natural light until his technique all but effaced the subject of his Water Lilies, from Piet Mondrian's grids to Jackson Pollock's bare numeric titles that somehow include both One and Number One, Modernism found in series at once a point of origin and a free play that cannot cease. With "The Unfinished Print" and an unsolved crime, I can at last see Munch the Victorian in that same mad pursuit.

The robbery at the Munch Museum in Oslo occurred August 22, 2004. "The Unfinished Print" ran at The Frick Collection through August 15. Related reviews look at Edvard Munch and "Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible" at the Met Breuer.