Control Freak

John Haberin New York City

Piet Mondrian

Galleries like to think that art is big business; critics of modern art harp on it. Now museums have finally pulled it off. Has any Hollywood focus group led to such consistently long lines? The formula for a "blockbuster" is predictable enough to suggest a focus group, too.

Think about it: to enter contention, a painter must have left at least one image that looks terrific over the sofa. Male to be sure, he was born safely before this ugly century, but no earlier than 1840. (Monet gets in just under the wire.) Large strokes of decorative color recall the buzz of modern life without too much of its discomfort.

Series upon vast series of his similar canvases practically cry out for the guidance of a museum catalog, without provoking the graver puzzlement of a right-wing politician. It helps if plenty of the work sits handily in collections of potential museum donors. Maybe I am imagining it, but it does not hurt either if the artist's name begins with an M.

Fair enough: Monet, Matisse, Miro . . . but Mondrian? Yes, indeed. The painter known above all for his austerity has taken everyone by surprise, including the critics. They have found the exhibition at New York's Museum of Modern Art a little less deep and a lot more fun than anyone could have expected. Mondrian turns out to be as joyful and decorative an heir of Monet as anyone could want.

Taking a deep breath

I am not (altogether) joking. The reviews could well have been written in collaboration. They start with Piet Mondrian, unmarried at his death, with the thin features and wire spectacles of a European schoolmaster. Could this man, they marvel, have delivered the flash of a painting called Broadway Boogie-Woogie? Meanwhile, the museum's own bookstore managers panic at keeping up with the unanticipated demand snaking out the door.

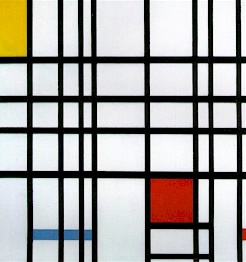

I have to admit to the same relieved surprise. Mondrian's work looks imposingly regular, its near-symmetry earned the hard way. A small square of primary color just balances a large square in another corner, which in turn could easily teeter over the edge of confusion without a saving black bar someplace else. Taking it all in is like holding one's breath.

This show comes like one long, relaxing exhale. It begins with brooding landscapes and modern still life painted in Holland. In these and later paintings influenced by the Analytic Cubism of Picasso and Braque, outlines escape to take on an active life of their own. The delicacy of the lines resembles nothing in Picasso, however.

Also as in Cubism, the corners of the image at first drop out. In this way, ordinary things and abstract forms can float, suspended for contemplation. The fragmentation slowly opens up Mondrian's art to fields of calm, steady white.

In his best-known paintings, a firm rectangle returns, the areas of bring color expand, and the lines reach out to the painting's unframed edge. Under their pull, the center no longer holds. Rather than enforcing symmetry, Mondrian kept on finding novel means to break it. He always starts with a form and lets his paint stretch it apart.

Later still, after the painter's move to America, the color rectangles stay bright but grow smaller. They take on increasing activity, like blips on a crawl screen. Shortly before his death, they indeed come to recall the staccato accents of New York City thoroughfares. With the tribute of appropriation, Melissa Gordon even likens them to the front page of a newspaper

This show's secret turns out after all to lie in that formula for a blockbuster. It asks that one reconsider why art sought the appearance of anonymity. It asks why symmetry breaking had such vitality. Paradoxically, modern art has depended for its color and variety on works in series.

Serial killers

Artists have always returned to a few preferred subjects, like Raphael to his Madonnas. Works make sense only as they jostle consistently against their own history, their creator's uneven but unshakable impulses, and a viewer's steady demands. Originality actually demands repetition.

Then too, beginning in the late Middle Ages, personality grew more and more important to the reception of Western art. An artist's style had to reflect the erratic course of a human life. Formal qualities might therefore evolve almost like a shift in genre. One speaks of Rembrandt's Leiden period or his murkier late phase.

By a series, I mean something different—neither a style nor a period. That something began only with Monet's haystacks and footbridges. No single painting could encompass his ever-changing scenes. No single canvas could claim to be the best in its series. Their common impetus became as crucial as expressive differences among them.

Think of Modernism's generic titles: Monet's late Waterlilies, Picasso's many Women, Kandinsky's abstract Compositions. My examples are not arbitrary. Mondrian's earliest model, Impressionism, already refused to detach figure from canvas background. Like Picasso glorying in his arrogant desires, Mondrian stressed his superiority to any mere subject matter. Along with Kandinsky, he struggled to make his paintings free of reference while insisting on the "spiritual" in art.

After World War II, series continue to proliferate, and titles even flaunt their anonymity: Pollock's Number One, Warhol with his Orange Disaster, Frank Stella and Stella's Protractors. They imply much more than that Stella, an Ivy League graduate, passed his math requirement: They dare one to tolerate the possibility that the series could be churned out indefinitely. Mondrian did not live to see Pop Art, but he did much to convince Peggy Guggenheim to open her influential gallery to Pollock.

Works in a series pull the rug out from under their own uniqueness. As Rosalind Krauss has argued splendidly, they undermine the whole myth of artistic originality. They cast doubt on the notion of solitary inspirations from a lonely genius.

I have rephrased Krauss's insight so that, I believe, it holds up. Yet pushed to its limits, like a series in its own right, her argument against originality is way too dogmatic. Modernism necessarily grounds diverse aims and achievements.

A series can deny creative variations among its works—or call attention to them. A series can obviate creative development—or trace it in gory detail. A series' very existence might declare an artist's special breakthrough on a grander scale than any one painting ever could.

Modernism does not simply dissolve artistic production into the mass market. What is at stake is the very definition of creativity, even in Mondrian drawings, the very function of an avant-garde. A series puts these terms in doubt while recreating them in its own image. How might that discovery have worked for an artist of Mondrian's time? How did it underlie a lifetime subverting stasis and symmetry?

Art in context (of itself)

A series is first of all an artistic manifesto. It demands that one judge a work first in relation to others like it, not by standards of the past. The frequent written manifestos of Modernism, such as Manifestos of Surrealism by André Breton, declare a movement. A series too invites others to extend the enterprise. Mondrian called his program simply De Stijl, "the style," and it informed even designs for chairs and, with Frederick Kiesler, bookshelves—one of which inspires David Diao to this day

Compared to the academies, with a school's uneasy relationship to creativity, that enterprise no longer means copying nature. No one of Monet's haystacks claims to represent the scene definitively. Perhaps there is no way to grasp appearances at all. With each of Mondrian's variations, the world seems further and further away.

A series pushes toward inventing abstraction in another way: its fixed repertory calls attention to repeated patterns within a canvas. Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois, a contributor to the exhibition catalog, have thus connected series to the geometric grid so crucial to modern art. Cubism's oval canvases echo a dressing-room mirror. Mondrian's adoption of a rectangular format tears that metaphor to shreds.

Like a grid too, a series is as absolute a standard as the ultimate scientific catalog. It no longer mirrors the world, but instead it stands to reality as a comprehensive map. In Mondrian's New York paintings, a single canvas is like a literal map of the fragmented modern metropolis.

A series aspires to be all-encompassing. Think of Monet, hoping to catch every variation in daylight falling on those haystacks. From his dabbling in spiritualism to his stern insistence on abstraction, Mondrian too always associated art with an absolute. He tried to avoid variation in surface texture as mere distraction.

A modernist series plays itself out against the assembly line. It manages both to emulate and to parody means of mass reproduction. It neither holds out the pretense of high art nor revels in a culture of corporate control. Rather, it subverts the distinctions between art and culture—or between art and life. De Stijl therefore also extended to architecture and furniture design.

A series is almost a respectful parody of both artistic production and the assembly line, like Chardin's modest pots and pans formally trademarked. Just as it undermines any fixed notion of tradition or representation, a series opens art to constant transformation. It is much the same constant transformation as in Cubism or modern fiction. The image reflects on its own possibility, its own tenuous meaning, in relation to others like it. No wonder I found at last that Mondrian was happily engaged in breaking symmetry.

A series permits unending variation. It does not abolish differences. Its formalist drive even highlights them, because subject becomes so bound up in its execution. Diversity evokes a life in which games take on the psychological weight of work.

Appropriately enough, Mondrian's last studio, reproduced in the museum, stood right around the corner from what is now F. A. O. Schwartz. Little kids in a toy store are not married either. If this art cannot, I am afraid, exactly be sexy, at least it can play fast and loose. One can see why Laurel Farrin is able to combine Mondrian with a crossword puzzle.

The work of a lifetime

The show taught me to see Mondrian as Monet's successor and Kandinsky's contemporary. I think that brilliant insight accounts for the exhibition's few biases as well. The museum touches only lightly, for example, on Mondrian's early chrysanthemums, which do not so easily fit into the evolution of his series. Without his most popular works, he has ironically found his largest and most receptive public ever.

The retrospective works so well because it always insists on two great modernist urges: refusal and production. In his series, the artist stands apart from both art's deadening history and modernity's numbing present. At the same time, the artist also aspires to produce something that rivals, colors, and ultimately enters everyday life. Art functions both as critique and as play.

The retrospective naturally takes particular pride in the large New York paintings, which belong to the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection. This climax gives the exhibition one more reason to remember the series, for here Mondrian abandoned them. He tries to pack all the activity and insight of a lifetime into a painting. By doing so, he humbly asks one to consider the limitations of a lifetime's enterprise.

Demanding dreams

Modern art could never fully make good on its promises. No art ever can. Even on its own terms, the idea of a series is less coherent than I have hoped to suggest. It comprehends the world and abstains from it; it maps the cosmos in an atlas that is always overdue for revision. It suggests an art that can never be realized, an art of shifting meanings, but also an art in almost pathological need of absolute control.

Starting with Minimalism, the combination could at last allow itself to fall apart. In the '60s artists spun out quasi-mathematical structures to the point of incoherence. A grid now took painting away from finely tuned compositions: Symmetric or unbalanced, they evoked bankrupt cultures and an overly bankable art market. As performance art or earthworks, a series could now fall apart in the hands of its audience or decay into a natural site.

As I say, the implications of Modernism were never simple or undivided. Now a series had to reflect new impulses. Series that grew from scratch, like a mathematical deduction or logical hypothesis, suited postwar America. (My country still believes, or pretends to believe, that anyone's history can be reinvented overnight.) Now a series could finally be pursued to its bitter end, but Mondrian's ideals had to pass away.

Probably the rigidity of his dream explains why he will never be a favorite artist of mine, even after this retrospective. The experiment never quite leaves its laboratory. I shall never be entirely at home in the cracked, indifferent surfaces of his oil paints. As the piers of the North Sea are abstracted away bit by bit, I think of air being sucked out of the room. Maybe it is never quite safe to exhale after all.

My own favorites probably remain a kind of sidelight to Mondrian's career, his diamond-shaped canvases. Turning the rectangle 45 degrees emphasizes the irrationality of its grid. The series is mostly just black and white, giving the variation in line its greatest weight. The simplicity of the results can recall the poignant austerity of the Abstract Expressionists. Mondrian's better-known rectangles look busy by comparison.

I may still face a Mondrian the way Monday-morning commuters encounter late-modern architecture, but at least I shall think first of the Empire State Building. I shall better understand too why the return to symmetry with an artist like Mark Rothko was such a majestic risk.

Piet Mondrian's retrospective ran through January 23, 1996, at The Museum of Modern Art. A related review looks at Mondrian at the Guggenheim.