Stage Door

John Haberin New York City

Sara Greenberger Rafferty and Samara Golden

Everything, Everyday in Harlem

Sara Greenberger Rafferty is not keeping you out, honest. It only seems that way.

If a painting or a photograph is a window onto the world, she offers instead a door. And if it is a kind of theater, hers instead promises to open onto a theater that one will never see. Could everything lie right there after all, before your eyes? Painting and sculpture often stops just short of installation these days, while piling on loose scraps and even looser allusions.  It does for Samara Golden, with the entire gallery as a hall of mirrors that, like Rafferty's, one cannot quite enter. And so it does, too, for the 2015 installment of artists in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, with "Everything, Everyday."

It does for Samara Golden, with the entire gallery as a hall of mirrors that, like Rafferty's, one cannot quite enter. And so it does, too, for the 2015 installment of artists in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem, with "Everything, Everyday."

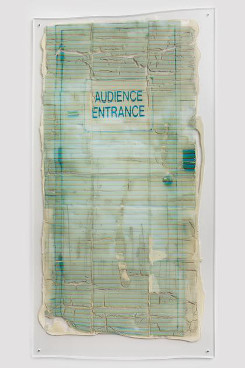

Audience only

Sara Greenberger Rafferty has a history of holding back, and her gallery has enough space to keep anyone at a distance. The front hall alone would suffice for most artists, and only halfway down does she present her first welcome—or obstacle. An inkjet print embellished in acrylic rests on one plastic sheet over another. Screws anchoring it to the wall count as part of the work, much as for Robert Ryman, but with neither clarity nor opacity a given. Block caps in spindly sans serif identify the work as an "audience entrance." That, I suppose, means you.

Perhaps, but entry here does not come easily. The work looks more like Venetian blinds than a door, only the worse for wear and for its slight departure from an even rectangle. It offers nowhere at all to go, other than to the gallery's other rooms, which have more of the same media. Images include stage mikes, twisted uncomfortably near the floor, and curtains, but also a daring or vulnerable woman—and who is to say? To add to the puzzle, an ordinary entrance is always for the audience, as opposed to a stage door. It is also not often made of plastic.

Rafferty has played the audience before, as well as the performer. For "Chick Lit" a summer earlier, she photographed herself with grimaces that could have meant genuine agony or ham acting. At PS1 in 2006, Rafferty's videos subjected her to a pie in the face and more. She has also rephotographed prints after TV. Here she can claim two distinct bodies of work, one personal and one for the stage, but which is which? A stool surely awaits a musical performance, but why is it smothered in plastic of its own?

Her pain and performance go back to Cindy Sherman, to name just one. Her nurturing of surfaces while disclaiming responsibility for their making fits with many in the present, as does her space between photography and other media. They are a way of having it conceptually and eating it, too. With performance cues that include recycled dance diagrams, they boast of their recourse to a formula. Yet they also open the door to experience. The audience is about to enter.

Nick Doyle, too, tries a little too hard to put on a show, but it takes hard work to combine comedy and trauma. His own Venetian blinds, and indeed he has them, come with a miniature electrical outlet, as if to let you in on the act. A sliding red tongue does not really need art to insist that it is capable of sticking out. Death Blow sounds a bit much anyway. He can claim a schlubbier alter ego, Steven, but the name in lights, as in a stage dressing room, does not say much as art. One will just have to take his word that "downtown," perhaps Vegas as seen in a light box, is the character's sorry home turf.

Still, Steven has a knack for household devices, as setting for actor and audience alike. The Realm of the Sun tops a projection screen with a microphone, while an old TV makes the perfect counterweight for a sphere of still more stage lights. Candles rest half melted in Cave of the Unanswered. Often he blurs the line between privacy and performance, with an unmade bed, a small upholstered chair, or a fan set against spackle. What looks like a guillotine amounts to a small keyboard instrument, and an eye out of René Magritte rests amid a color wheel from Beyond the False Mirror. If you tire too soon of Rafferty or Doyle, no doubt so do they, and they want you to know it hurts.

Climbing the walls

Samara Golden is big on creature comforts. No crawling through her installations on one's hands and knees, as with Mike Kelley, to discover only the cold comforts of a Fortress of Solitude. No fears of stumbling in a hall of mirrors, as with Yayoi Kusama, or banging one's head. No sense as with Kara Walker in Williamsburg for A Subtlety or Mike Nelson on Essex Street of the very ground beneath one's feet slated for demolition, along with its history.  No, she supplies comfortable seating and the promise of hospitality or home. Just do not expect to enjoy them any time soon.

No, she supplies comfortable seating and the promise of hospitality or home. Just do not expect to enjoy them any time soon.

Everything from Golden remains out of reach and in dizzying. A Fall of Corners keeps its distance from the start, past the gallery's barren front room. And then one crosses a diagonal catwalk in a darker space filled with ominous music, where the fall begins. It may not be treacherous to look down in practice, but it sure is mentally, given the illusion that she has excavated a floor or more below into the Lower East Side. Tables, chairs, and sofas rest empty as if after a rushed evacuation. Furniture is, literally, climbing the walls.

It is, that is, except where it is not. Golden has paved the floor with mirrors, reflecting wall coverings and furnishings from above. When she placed everything upside-down in the duplex gallery at MoMA PS1, through August 30, their image came together reassuringly enough in reflection. The installation even sounded reassuring, as The Flat Side of the Knife. No danger of injury here, just the side for butter or a spread. The virtuosity of presenting an ample room in reflection was itself comforting.

The knife had an edge all the same. The room had warm brick walls, musical instruments, and plenty of windows, but also a wheelchair tumbling down a steep staircase. Still, it approached a one-liner, as easy to dismiss as to appreciate. Kelley and Kusama, here we come. Her latest does much more to upset its own illusion. It really is a matter of falls and corners, with things not on solid ground but on the walls.

She also makes it harder to keep track of the jokes. The walls to one side have posh table settings and, across the corner, the informal settings of an outdoor reception with a buffet table to match. The walls to the other side have the luxuriant white sofas of a hotel lobby and, again across the corner, what she identifies as a bachelor pad. Are they one scene, two, or four—and where does each begin and end? Are they still setting up, or have they indeed precipitously shut down? The bachelor pad has an exercise bike, but also the stepladder and paint cans of a work in progress.

The hotel, for that matter, has a Christmas tree and artificial plants, but that leaves open whether they are representations of live plants or of lifeless artifice, in a setting where hospitality is an industry. A video below takes a second life as a skylight above—or maybe the other way around. The catwalk ends in a pile of bodies, in black with party colors. Are they stuffed demons or cuddly toys? Could they be the victims of the casualty that emptied the rooms? If this is still fun and games, the stakes are increasing.

Scrappy

Artists in residence are supposed to be scrappy, like Open Sessions for the Drawing Center, and so is the Studio Museum in Harlem. With just three modest floors for exhibitions (and plans for growth), it finds studio space for three artists and wraps up each year's term by exhibiting them—this year on the mezzanine above paintings by Stanley Whitney, who settled down long ago. It also keeps up its periodic shows of emerging artists, and two of its latest residencies emerged from the 2013 version, "Fore." Both programs have introduced artists worth remembering. For this year's artists in residence, scrappy also means playing with scraps. In a show called "Everything, Everyday," that can encompass almost anything, much like art today.

Speaking of residence, for anyone raised in New York the coolest part of the Met may well be fragments, too, but of a pyramid. Not that all kids are as morbid as vampire movies, but even adults can find comfort in entering, and it sure beats all that old art on the walls, right? At least it does for Lauren Halsey, who uses a narrow hall for her version, in carved blocks of foam. Her installation finds its way from ancient Egypt to urban glitter—or, in reverse order, from her roots in LA to New York. The carvings bring things up to date, with faces and text echoing familiar voices, like "we will save our people" or "choose life." And an adjacent room indeed chooses life, with cartoon portraits, reused decals, and mounds upon mounds.

Halsey calls the installation Kingdom Splurge, crossing the ancient kingdom with "Planet Splurge" by P. Funk. It is also highly undisciplined, a hallmark of the entire show. Here scraps can run to old clothes, old bedding, old neighborhoods, or old memories. Sadie Barnette, who earlier customized a boom box, has not even settled on a theme or a medium. Just three photographs, a handful of sketches, and a mix of old clippings all point in different directions. They have in common only lost causes and lost connections, waiting again to be found.

Lost but enduring causes include The Autobiography of Malcolm X, falling apart from overuse, and a typewritten letter from the time of a movement to free Angela Davis from prison. Connections include Barnette's family tree, in meticulous drawings. The fine lettering suggests a loss to her, but also a greater relevance to others unseen. The clippings hone in on memories of a single connection, her father, and his fondness for the racetrack. As for the photographs, they linger over a neon sky above a Harlem air shaft, a calcified toy in a rattan chair, and plastic shapes on a front lawn. The shapes do not quite fit together, but they come close.

Eric Mack approaches a single body of work, with old fabric never altogether affixed to the wall. Bedding has fallen apart, and a windbreaker looks patched together for a cold winter night. Grommets make them more impersonal, but also more ready for use. Like the jacket, shapes have a habit of taking human form as well. Studio Museum residencies invite artists into the community, like Halsey on her way to New York, and Mack finds a special scrappiness there, too. "There is something about how people walk down the street in Harlem that is different than anywhere else," he says, "a 125th [Street] swag."

All three are still getting over the swagger. If the show looks scrappy, it also looks awfully familiar. Many out there are throwing around everything and the everyday, with unstretched fabric and trashy installations. The museum has taken up the idea before, too. It titled previous residencies as "Material Histories," "Evidence of Accumulation," "Things in Themselves," and "Scratch." Here it will have to settle for scraps from larger and firmer bodies of work yet to come.

Sara Greenberger Rafferty ran at Rachel Uffner through December 21, 2014, Nick Doyle at Invisible-Exports through November 23. Samara Golden ran at Canada, "Everything, Everyday" at the Studio Museum in Harlem, both through October 25, 2015.