Land of the Free, with Style

John Haberin New York City

Freestyle

In a show called "Freestyle," free and style lie so close, like parent and child on another endless vacation. Excited, hopeful, carefree, and impatient, they ask about the very possibility of a black art today. They also challenge the supposed objectivity of a white response.

They demand freedom for an African American but come hauntingly close to taking it for granted. They insist on blackness as style but risk leaving it as nothing more than style. They put black artists in the forefront of experiment, but they could easily reduce all that to a game in this year's all-absorbing market. They twist between personal hopes and impersonal trends, between anything and everything to each person. They do it all self-consciously, too, which surely makes "Freestyle" the most engaging show in New York in a long time.

From style to laughter

The Studio Museum in Harlem does not wish to pose unanswerable questions. Thelma Golden in fact has her answers a little too lined up. The museum's top curator, she put the show together with Christine Y. Kim. Golden claims to return to the museum's original mission. It will "present the cutting-edge of contemporary art by artists of African descent." Asking for it, now that "original" comes with postmodern quotes? Well, yes and no.

I was ready to hate the show. The mainstream press has hardly so much as mentioned exhibitions uptown in a decade. Suddenly, it seems overjoyed to see black artists wrestle with black and white America, freestyle. Remember black power as seen through Western art, with Barkley L. Hendricks and European painting as African American portraits or with the Dean collection and "Soul of a Nation"? Things have changed—and not necessarily toward black liberation.

Golden's line sounds right off like an evasion of history, starting with the museum's own. Recalling a mission sounds great, but writing off the years sounds suspiciously like betrayal. The line even sounds like a throwaway. After the 2000 Whitney Biennial and last summer's "Greater New York" at P.S. 1, this group show could stand for the excluded—the black as truly other. Yet it also announces one more attempt to keep up with the crowd. Among twenty-eight artists, each with a couple of works or so, no voice gets to rise clearly above the others, and the echo trails off all too quickly.

Besides, the word style—like the attendant publicity—comes all too naturally to Golden. As she came to the museum, papers never failed to note the art-world parties she last attended. Her show at the Whitney years ago, "The Black Male," made her a star while irritating everyone. One side complained that it stereotyped black men. The other argued that it left them off the hook, making their posturing into mere art. Yet her new show works, because it really does start one thinking about black artists and black identity.

It says more than a little just by turning its back on the carnival atmosphere of "Greater New York." The exhibition takes up the lobby and one large room, with side alcoves. The long balcony adds display space, plus fresh perspectives on the art below. Any single artist's works may stand apart, giving them breathing room and letting a visitor draw the connections. They become something greater and more like New York after all, an imperfect world of black and white.

The glass storefront could pass for another government office building, although it hides a museum and space for working artists. (Remember the name, a "Studio Museum.") Welcome renovations coming up should increase room for display, archives, and performance. They will also convert a small adjacent lot, like barely illegal parking, into a sculpture garden. Right now, however, things inside have quiet proportions. Here distinct, narrow lives stay hauntingly close but mutually out of reach. Here, too, a bitter swipe at the other can shift easily into self-mockery and back again.

Self-reflection, in black and white

Golden calls her show "post-black art," and she has a museum that can even present black abstract artists, a black artist collective of the 1960s, or black conceptual art as a lost tradition. Still, she sees her artists, like all black Americans, as never escaping their color. She sees artists living it, just as with their own emerging memories. Only she sees them as able today to respond more and more personally, not so much in anger as with beauty and humor. More often than not, images and jokes have a way of turning inward, too, reflecting on blacks and the artists themselves. Whenever black and white American come into question, so might the very idea of something in black and white.

Take perhaps the very first thing one sees—a row of large, black-and-white photos of a black man's face. He looks out, staring blankly in harsh light. He looks down, eyes almost shut. He nowhere at all that one can say for sure, hands drawn across his face. He looks in pain—and pretty darned painful.

Does that outward stare mean defiance or blankness? Do the downcast eyes mean inner complexity or shame? He could be frightened, completely drugged out, or just trying to hold his own between a ghetto and a white man's world. Yet the huge prints give him enormous presence.

Rashid Johnson brushes the black right across the paper, leaving a white border brought alive by broad traces of a human hand. A friend said that the subject made her think of Morgan Freeman or some other film star. The process made me think of the glory days of American art and artistic self-destruction. It took me back before Willem de Kooning and gesture gave way to Robert Rauschenberg and a sign-painter's hand.

The constraint of black and white suggests the extremes of a nighttime world. It evokes ink and so an artistic signature, the simplicity of a cultural icon, and black or white identity. Like a later show at the museum, it questions the availability of race as "haunted files" and "usable pasts." It even asks one to think outside the limits of "Greater New York" and art-world politics. Johnson and his subject hail from Chicago.

That opening display very much sets the show's tone. One finds oneself drawn to work as part of art's mainstream. It seems plain old gorgeous or humorous, even almost abstract, as if assimilated entirely into art and white expectations. And then one teases out explicit reference to black images and experience. One ends up with the same easygoing but troubled questioning of the show's title, but with art neither personal nor societal responsibility ever go away.

Masks and child's play

These artists start with old-fashioned presence that black artists just a few years older find suspicious. Then cultural associations start piling in, leaving presence a mere mask, almost as for Ralph Eugene Meatyard in white America. Only instead of hiding an authentic blackness, the mask of art itself stands for the puzzle of identity.

Louis Cameron and Jennie C. Jones do it with abstraction. Cameron's grids lie flat on the floor, like the classic Minimalism of Carl Andre. Their shapes, however, make me think of southern peanuts, a paper medium the fragility of survival. Jones's wall grid recalls Mondrian and Russian Modernism, but a girl's photo sits just off center—"an unknown black suburban girl." Instead of spiritual truth or a revolution, the grid suggests a network too open and unbalanced to add up, far too complete to avoid entrapment. Lovely architectural photos from Kira Lynn Harris also verge into abstraction, as do Julie Mehretu, her urban architecture, and her abstract murals, which can recall Gary Simmons and his memories drawn right on the wall.

Photographs by Rico Gatson look gorgeous, too, and the viewer, black or white, bears the responsibility if flames evoke a lynching or a burning ghetto. Dave McKenzie shoots himself in video, as a street artist, tap dancing to the point of spasticity. Passers-by ignore him as best they can. Adler Guerrier photographs airports, as desolate way stations on the way to nowhere. Again one asks who has abandoned whose future.

For other artists the break with Modernism comes in the medium. Mark Bradford makes his abstractions out of curling papers, and Kori Newkirk creates a surveillance helicopter out of pomade. A doorway breaks the startling, all-black silhouette, just as the smell and color identify it with the victim as well as the oppressor. Camille Norment has different tones ring out of each metal pole in a black, padded room. The sounds make thoughts of a subway car or madman's cell that much funnier and creepier.

My favorite oddball medium introduces another of the show's themes, cartoon visions of blackness. Senam Okudzeto paints on phone bills, with deft schematics of a couple facing off or making love. The drawings hover between Eastern miniatures and porn. The numbers, dangling on the wall, offer a tale of love, violence, and unaffordable monthly bills that never ends. While Laylah Ali's heads make a perplexing caricature of blackface, Kojo Griffin's street-fighting teddy bears offer more disturbing laughs. At least in his drawings, he makes arrests none too welcome, but also a part of the black community's life from childhood.

Tana Hargest knows kids, too. Her funny tale of a black dealing with the marketplace is an interactive video game. Other new media include a split-screen video by Sanford Biggers of twin birthday parties, black and white. Childhood memory, a place of longing, becomes a longing for racial divisions to vanish somehow for good. Adia Millett's dollhouse also calls on memory. Its empty rooms, cluttered with cut-rate consumer goods and furniture, seem as familiar as poverty and distant as a dream.

Postmodern and post-black

Like collections of junk, even these, no show of twenty-eight artists exactly works. I live in the period of installation as shopping mall, just as Eric Wesley gets serious mileage out of piling up junk-food packaging. Even those I have mentioned can let me down. They strive so hard for the busy and schematic, at times, that a pretend naiveté falls flat. They can deal with what Golden calls the "post-black," but they cannot get around it. They make it easy for this secular Jew to relate to his own torn identity, but a little too easy for the balance of power in urban America.

Perhaps no show uptown can have an impact on a white man—or even a black African—comparable to being there. I mean not just a small, lovely gallery, amid the cheap facades and blank government towers of 125th Street. I mean the mix of wonder and sadness for me, a frequent visitor and native of New York confronted yet again with America's racism and extremes of wealth. When the same museum exhibits a contemporary generation of exiles from Africa, what will I think?

I could hear the show's title as I walked past harsh reminders that the black experience is anything but free and with little mental, physical, or economic room to be stylish. I did not spot Bill Clinton near his new office. Beyond a handful of museum visitors, mostly European, I never saw a white person other than myself and my companion as I walked for miles. I hardly knew to marvel or to feel shame at Harlem's old brownstones. Should I take a boarded-up facade for a burnt-out building, an artistic and historic past, or a recent spurt of gentrification and recovery? Should I take the latter as a sign of hope—or a sign that the residents can no longer afford their own fragile neighborhood, always close to the classiest black community in New York.

Of course, cities change, and signs shift, even within a single vision. Black artists, such as Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin, have always captured that change. Across the entire face of America, black and white, people struggle to learn whether they benefit or get left behind. At the far side of a booming economy, the sense of responsibility for a black's own identity becomes more striking.

I speak as a perpetual outsider myself, the other, be it in mainstream culture, the arts, or the black community—just as voices in this show speak as the other to me. Maybe that is why I appreciated long wall labels, taken from the catalog. They neither claim to hold all the answers or block the works, a relief after the Met.

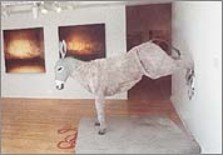

Freestyle is style, but "post-black art" is defined by blackness, just as Postmodernism can survive only as long as it keeps Modernism a force along with it. Take Wesley's Kicking Ass, a life-size donkey. Surely a white sculptor, like Deborah Butterfield, would prefer a horse. Does Wesley, with his racy title, ridicule white images of blacks or the limits of street culture? Or does he really mean to kick ass? I can only tell you that, as I turned a corner, the hole its hoof punched through a wall took me by surprise—and points back toward the street.

"Freestyle" ran at the Studio Museum in Harlem through June 24, 2001. Related reviews looked at its other surveys of emerging art—"Frequency," "Flow," "Fore," and "Fictions."