Poetry, Language, and Memory

John Haberin New York City

Archie Rand, Hollis Sigler, and Frédéric Bruly Bouabré

"You know it: I must lose you again / and I can't."

Eugenio Montale must have felt the loss just as intensely the second time, in describing it, thanks to the power of language to sustain memory. He must have wondered if the act can ever bring closure. He must have wondered, too, how much he even wanted release. Memory also brought her back to him, and readers of his poetry will experience his loss along with him once again long after his death in 1981. Now others can experience it as well, in paintings by Archie Rand and Hollis Sigler. Sigler, though, finds her text and death in a frame, a sampler, and a deal with the devil.

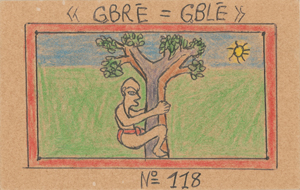

Just a guess, but I bet that you were an early reader and have loved books ever since. You are, after all, keeping up with challenging reviews, not just mine, of a challenging subject, art. If I have that wrong, though, take heart. You may have struggled with the ABCs, but it could have been a lot worse. You might have had to handle not just twenty-six letters but the four hundred forty-nine entries in Alphabet Bété, by Frédéric Bruly Bouabré. And they are just one of eleven series in "World Unbound" at the Museum of Modern Art.

Losing it

Montale wrote his Motets in the 1930s, and they do achieve a modest degree of closure. The very last in the series begins ". . . so be it" and ends with an acknowledgment that life, "which seemed / immense, is smaller than your handkerchief." They make a point, though, of indeterminacy. They do not spell out that he lost a loved one to her death, for all their intimations of mortality. And then, starting in 2013, Archie Rand devotes a painting to each of the twenty short poems, with intimations of his own. He scorns "obedience" to the poetry, he writes, in the hope that text and image can "agree to a mutual invasion."

Rand has based work on the Italian poet before, but agreement is never easy, no more than for Tiona Nekkia McClodden with queer or African American poetry. If art sticks too closely to text, one might dismiss it as illustration—and if it departs too greatly, one might dismiss it as self-indulgence. While the paintings hang closely together in a row, like a graphic novel, they also cry out to stand apart. Their heightened colors lend his narrative a childlike intensity, while bold outlines fix it in place. Other figures, exclusively women, fade into softer and flatter tones, as images of memory and loss. A young man with bright yellow skin throws up his hands at it all, because who can say which is more real?

While the shadowy women float just above the picture plane, the rest of the busy cast occupies a deep but indefinite space with a debt to Surrealism and Giorgio di Chirico. A two-lane highway stretches to infinity. It is a mythic cast at that, filled with horses, warriors, and a crucifixion, none of them in the poems. Where Montale sustains a melancholy distance, Rand brings comforts, clashes, and action to his dreams, with those rearing horses and a slow dance. His technique makes the action palpable as well. His canvas includes additional fabric fragments, bunching up now and then to reinforce his drawing.

For all his reticence, Montale brings the immediacy of sounds even apart from the sound of words. He speaks of fireworks, "a sudden railroad rumble," "an underwater tolling," and "Hell's piano player." Rand, who has performed on piano, must relate. He has also illustrated American poets like John Ashbery, Robert Creeley, and John Yau with a particular concern for music and the visual arts. And he does so again in 2017, with two poems by David Shapiro. While he can hardly have worked side by side with Montale in Italy, both he and Shapiro consider these works Collaborations.

They are singularly American. The shadows and myth are gone, in favor of violence and humor, with one foot in film noir and the other in the comics. A robotic villain carries off a barely clad blond, who may or may not object. A teddy bear clutches a ball while smiling along with you at the show of sentiment. They come closer to you as well. The loose spaces have become yellow-orange walls, a huge yellow sun or moon, and a curtain of blue, black, and red skies.

Shapiro's verse appears in speech balloons, but just who is speaking? The Milky Way is shrinking, while girls in their summer dresses huddle beneath their umbrellas, and the cherry blossoms are growing, while a man rests beside his horse like a cowboy with nowhere to go. Men fight over a knife, but "I tell you / Never plunge it straight." He alludes to Emily Dickinson: "Tell all the truth but tell it slant." Text and image make one extended slant rhyme.

Let's make a deal

When Hollis Sigler paints domestic interiors in loose lines, deep color, and symmetric compositions, you might be put in mind of a sampler. When you find text at the top, you might expect it to read Home Sweet Home, not I'd Make a Deal with the Devil. It takes only a moment, though, to realize that these are more sophisticated than she lets on. Folk art for her was an adopted home, one that she nurtured and loved. If it had room for fears of death, it also put her in mind of the women who came before her. As for the devil, rest assured that Sigler got the best of the deal.

The Chicago artist paints a woman's world, her world, but in truth it is something of a stretch to call it domestic. It has her easel, but few other possessions, and they, like her brushes and palette, lie abandoned on the floor. People are nowhere to be seen apart from an empty dress or a woman's silhouette. The gallery speaks of the aftermath of something unspoken, like sudden flight or a party, but she seems unlikely to have welcomed guests. When her breast cancer returned in 1992, she had all she could do with thoughts of her mother and grandmother, who died of the disease before her. She was, another title has it, Walking with the Ghosts of My Grandmothers.

The Chicago artist paints a woman's world, her world, but in truth it is something of a stretch to call it domestic. It has her easel, but few other possessions, and they, like her brushes and palette, lie abandoned on the floor. People are nowhere to be seen apart from an empty dress or a woman's silhouette. The gallery speaks of the aftermath of something unspoken, like sudden flight or a party, but she seems unlikely to have welcomed guests. When her breast cancer returned in 1992, she had all she could do with thoughts of her mother and grandmother, who died of the disease before her. She was, another title has it, Walking with the Ghosts of My Grandmothers.

She was likely to be a ghost herself soon enough, she knew, and she died in her early fifties in 2001. That silhouette may float above an interior open to the sky, when it is not meeting the devil. The painting on an easel depicts another empty dress. Still, ghosts have at least one advantage. They glow in the night, like Sigler's art. Sconces on facing walls are a broadening circle of light and color, and skies are full of stars. Double doors have a glistening daylight blue from their glass or curtains.

Glass implies naturalism and curtains drama, and she has her share of both, up to a point. Her adopted simplicity insists on something more naïve at heart. These days, outsider art can mean almost anything, and Sigler felt drawn to its growing popularity after studies at the Art Institute. If that sounds awfully calculated, remember the love. Remember a heritage in floating figures like those of Marc Chagall as well. Remember, too, the risks in a sky struck by lightning and the devil.

The devil here is a skeleton, not a figure likely to sweet-talk woman, and the silhouette raises her arms to meet it and the lightning on equal terms. Other hands reach up from the painting's bottom edge with all sorts of bargaining chips. I cannot swear who is offering them, but they have nothing on the sunset-red earth, dappled walls, and starry sky. The intrusion of a skeleton into everyday life goes back to the Dance of Death in earlier art, as in Renaissance prints by Hans Holbein in Tudor England. See, they say, even lords and lawyers face death, and so will you. Sigler, though, is anything but a moralist, and she does more than her share of dancing.

She does, though, spell out her feelings—not just in the centered titles, but also on the frames. The text changes direction as it finds its way around the four edges, in printed letters that approach a reassuring cursive. I leave you to make your own discoveries. The entire show dates from the 1980s and 1990s, when she became more and more focused on her breast cancer journal and the likelihood of death. At the same time, her colors were softening and her stories deepening, and the open drawers and doors promise all sorts of resources. She says that she felt an obligation not just to herself, but to the community, and she like those hands brings a gift.

Beyond the ABCs

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré cannot have had too much trouble learning to read. Born in 1923, he worked as a government clerk in the Côte d'Ivoire, or Ivory Coast, home for Joana Choumali in photography as well, with such tasks as translation. "Writing is what immortalizes," he said, citing influences from hieroglyphics to the Bété language of West Africa, and it sustains his art. His imagery is simple to the point of clumsy, on scraps of cardboard roughly the size of postcards. They would fit right in with hand-tinted photographs and other found objects at the American Folk Art Museum now. Like baseball cards, each has a thick border and, beyond that, a margin as a repository for words.

Still, he was a slow learner, because learning could never come to an end, in keeping with his conception of contemporary African art. He saw his mission as a "chronicle of the known universe." That alphabet, started in 1990, was just one step in what an earlier series called Connaissance du Monde—"knowing" or "knowledge of the world." Other hand-lettered text reinforces what MoMA calls his "obsessive cataloging and sharing of information," often repeating little more than a series title. As curators, Smooth Nzewi and Erica DiBenedetto claim for him "day-to-day activity from the household to farming to making music." He admired religion and folk tales as well.

Now if only he spent more time out of the office. If his imagery amounts to outsider art more than life drawing, he kept at his job until retirement in 1981. He has not shown often in New York—and always in connection with his native culture and folk art. He appeared in 1994 alongside Alighiero Boetti, who selected him for the occasion. Could Arte Povera, Boetti's movement in Italy, be another kind of primitivism? Bouabré could have taught them how to think big while working on the cheap.

Retirement allowed him to dedicate himself to art, but the task began earlier, with a revelation. He was doing nothing in particular, he said, when he had his "divine vision" on March 11, 1948. He recorded it only in 1991, in eight drawings in ballpoint pen and colored pencil. Each shows a sun, nearly identical but distinct, and that, too, is telling. Bouabré aimed to capture the world's diversity while seeing every element within it as a universal. He aimed, too, to discover symbols of the universal by sticking to the observed.

He saw his task as political as well. La Démocratie C'Est la Science de l'Égalité runs one title (or "Democracy is the Science of Equality"). Other series aspire to a Museum of the African Face and pay Homage to the Women of the World. They seek commonalties all the same. Semence de la Vie (or "Seed of Life") finds nude men penetrating not just one another, but anything that moves. When he draws Relevés des Signes Observés sur Oranges (or "Readings from Signs Observed on Oranges"), they are comically ordinary but no less ambitious.

So large a show passes quickly, like one long graphic novel, but its very crudeness has meaning. If his women all look pretty much the same, that only attests to universals. His alphabet begins with human body parts before running to all sorts of creatures, as little dignified as a tadpole. Bouabré's politics may be less revolutionary than he thought as well. He stuck with the French colonial administration, and text labels his women as pure to the point of "angelic," but try not to be too harsh on his hoped-for feminism. Changes were in the air when he died in 2014, at ninety-one, and he would happily have catalogued them, too.

Archie Rand ran at BravinLee Programs through April 25, 2020. Hollis Sigler ran at Andrew Kreps through March 18, 2022, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré at The Museum of Modern Art through August 13.