Turning to Blood

John Haberin New York City

Richard Mosse, Yoan Capote, and Juan Manuel Echavarría

After fifteen years and well over five million dead, the earth itself should have turned to blood. For Richard Mosse, it already has.

So it may seem in The Enclave, his video of war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Yet it is also achingly, unnervingly beautiful. Meanwhile the death toll continues, and so does the impulse to recover the living. Yoan Capote observes the refugee crisis in paint, while Juan Manuel Echavarría sees something more brutal still.  When Echavarría calls his series "Silencios," one may relish the silences. One may, that is, until one remembers the silenced.

When Echavarría calls his series "Silencios," one may relish the silences. One may, that is, until one remembers the silenced.

Death in infrared

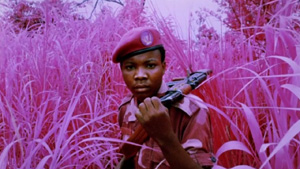

With Richard Mosse, large still photographs already transport one to another realm. A waterfall plunges through a supernatural landscape, between deep blue mountains and the acid red of some unknown vegetation. Whatever this is, it covers almost everything but the sky. Shining rivers snake through it, and soldiers stand amidst its tall reeds, so high that one can hardly call them undergrowth. A paler and smoother form of it gives rolling hills the appearance of red sands, but still it is down to earth compared to what unfolds in real time. This is Africa without the certainty of ritual, so far from Wangechi Mutu, Bathélémy Toguo, or El Anatsui because so fully in the present.

Mosse says that he was moved by a natural setting seemingly untouched by violence. As he has said about a previous project, he is also out "to question the ways in which war photography is constructed." Merely to look past the beauty, to people and their acts, is to see beneath the surface, and he and his cinematographer, Trevor Tweeten, apply a technique itself used to see beneath the surface—an outdated infrared film developed by the military to pierce distractions from the air. Converted to high-definition video, it gives plants their lavender red and the soil of roadbeds their turquoise blue, while leaving human flesh and deadly weapons alarmingly familiar. Children run and play as if even refugees had somehow escaped the cost of war. Clothing takes on heightened colors, like everyday habits refusing to die.

The art and science of the medium alone highlight the difficulty of documenting events. Even to assign a time span and a body count is taking sides. Conventionally, the Second Congo War began in 1998, although the First Congo war had hardly ended, and the players had hardly changed. Officially, it led to a peace treaty in 2002, but the footage here dates to 2012 and 2013 (when the video made its debut at the Venice Biennale). The conflict, more or less between Hutu militias and Tutsi rebels, as I understand it, drew in every neighboring nation—with the smallest, Rwanda, the most deadly contributor. Mosse never identifies the players, suggesting an objectivity apart from politics while leaving the viewer that much more at sea.

One feels in need of an enclave just walking into the darkened room, to a pulsing soundtrack by Ben Frost, based on African recordings. The video's forty minutes unfold on six screens, a rough square of two-sided screens and two on walls to either side, like MoMA's atrium for Julien Isaac but without the slickness or the mythmaking. Any given screens may show the same image, the same scene from different points of view, or only blackness. Mosse relies on long tracking shots, using Steadicam to follow soldiers on patrol through the dense brush and badly paved roads of the eastern Congo, as if walking with them. The seeming impossibility is unsettling enough, quite apart from the camera angle's frequent dips and dives. The viewer may be penetrating the action, but the action also penetrates the viewer.

At least since Stanley Kubrick, horror films have used tracking shots and narrow passages to build tension—and so does the camera's motion here, except that nothing lies at the end of the tunnel. One could find oneself anywhere in the middle of the action. The video starts with the landscape, but with roiling waters that look as if oceans had touched a land-locked nation. It turns to a community theater somewhere between a Sunday sermon and a dangerous circus, with men leaping through fire. Then come the patrols, automatic weapons and grenade launchers at the ready, and a refugee camp stretching as far as the eye can see. The children at play, a live birth, and a funeral all insist that life wants ever so much to go on.

It does not go on untouched. A soldier props up a body like a ghoulish puppet, no doubt as a warning, but others crowd around a dead body to take pictures with a cell phone. And then the rebels move in, and things do not get better. Born in Ireland and based in the United States, Mosse shares the point of view of an outsider—or indeed the viewer. One can hear chanting and song, but one may also notice the near absence of one-on-one conversation. People can touch one another, but they may never find an intimate peace until the bleeding stops.

Feeling the heat

Many on the right, in Europe and America, wish that refugees would just go away. Many would like to make their suffering invisible to human eyes as well. No matter, for Mosse has found a way to see what the naked eye cannot. That last exhibition turned outdated infrared film into high-definition video that gave civil war in Africa a surreal color and supernatural beauty. Now he turns instead to the latest thing, in both his medium and world events. He adopts military technology to photographs of refugee camps.

They have none of the temptations of a seemingly untouched nature, in Africa's waterfalls and trees. Here even the seas bordering on camps have the choppy grays of paving tar or hard stone. They have few, too, of the close encounters that gave civil warriors a brutal humanity. Mosse sees the camps from the air, in panoramas that seem constrained horizontally only by gallery walls. This film can capture detail at over thirty kilometers, or nearly twenty miles. By comparison, he points out, the horizon itself drops away far sooner.

The film can do so with an uncanny crispness, thanks to exposure times of up to forty minutes. The prints, which look much like photographic negatives in black and white, dare one to count the bodies or the fences. They give closely packed shelters, cars, and military vehicles a ghostly sheen. Early photography, too, needed long exposures, emptying Paris streets because people do not sit still. Here, as for Thomas Struth or Katherine Newbegin, film accentuates the masses and their immobility. It calls to mind, too, the obstacles barring movement in or of the camps, to safety or freedom.

Smaller accompanying photos allow for greater action, but only barely. All are displays of virtuosity since Mosse, after all, has only human eyes until he is done. (He says that he often has to discard the results, although he is getting the hang of the medium after two years.) He calls the work "Heat Maps," after the film's original purpose. That, too, calls attention to flesh and blood that others would rather forget, but almost everything here seems to give off heat. Humanity is itself in question.

"Insecurities" at MoMA displayed the barest of comforts that international organizations can bring to the camps. So does "Perpetual Revolution" with its photojournalism and social media. Julio Bittencourt has, more poignantly, applied ordinary photography to South America's dispossessed, while Latin American artists have placed "An Emphasis on Resistance." Yoan Capote looks again across the Gulf from Cuba, in paintings of sunlit crossings and stormy seas. Their surfaces of oil and black fishhooks pack a triple dose of native culture, photorealism, and treachery. His mix of hopes and fears emerges in title from Cold Memories to Luminous Future—and in the space between political art, landscape, and abstraction.

Each artist is recovering lives, while also questioning those who place lives in danger. For Mosse, the latest means do not require an indifference to the ordinary. Rather, he starts with the unseen. For him, too, the latest means do not require an indifference to the ordinary. Rather, he starts with the unseen and renders it unfamiliar. A print's very distance from its subject adds to the presence and the chill. For now, Trump threatens to throw diplomacy and refugees to the winds. Art and technology are already feeling the heat.

The silenced

Silences have become so rare, amid installations and openings so bursting with audio and visual noise. Nothing in Juan Manuel Echavarría's photographs seems disturbing either, at least at first and at least to First World eyes. Soon enough, one starts to notice the loose ends and the missing faces—enough to make one ask just who has been silenced. These are empty classrooms in Colombia, with every sign of life but the living. If the silences become ominous, though, one should not forget that initial warmth. Echavarría offers hope of a common humanity, even amid the political divisions of death squads and a drug war.

His interiors look inhabited enough, even without people. Class might be starting again any minute. Blackboards and hangings are ready for today's lesson in English, geometry, or geography. A hammock offers rest, and clothing hangs out to dry in overcrowded rooms, waiting for families to pick up. If the double purpose of schooling and domesticity is troubling, perhaps impoverished village life is like that. Even in New York City, schools err on the side of staying open rather than taking snow days, in part because children deserve a warm room, a warm heart, and a hot lunch.

Compositions, too, make a point of stability. Blackboards fall close to dead center, as one horizontal rectangle within another. For a lesson in "geometric figures," the circles, squares, rectangles, and a triangle painted on a wall pun nicely on the garments hanging to their side, in their own warm colors. Not everything, though, is so tidy and humane. Scraps and buckets pile here and there, with abandoned husks strewn across an entire floor. A line of dried tobacco adds to the aridity, and smeared blackboards hold out a less comforting silence. A cord hanging down almost takes the shape of a noose.

How long ago did death pass through? Have children found refuge only a day or a moment before, or have teachers begun reassembling after the violence? Echavarría supplies few clues to a world torn apart and unable to heal. One title identifies the map from a geography lesson as "political," and another identifies clothing with the naked. The photos document the striving to maintain everyday life, much as Mosse's video finds births and child's play after years of war in the Congo. Echavarría, though, leaves his scenes empty and in silence.

Six years earlier, he titled a suite of square photographs "Death and the River." He means the Magdalena River—the scene of drug traffic and unmarked graves. And here, too, the inhabitants take death personally. In fact, they have adopted the dead as their own. An individual tends to the tomb of an NN, meaning Ningún Nombre (or "no name"). They also thank the escogidos, the select or the chosen, for their favors from the next world.

From the look of things, the dead are not doing anyone any favors, but the care of the survivors has sustained a sad but beautiful sense of community. Like the classrooms, the graves accumulate objects and inscriptions, in human handwriting rather than etched impersonally in stone. They can become starker and more geometrical, but more distinct and colorful at the same time. Echavarría reinforces the variety, color, and geometry by arranging the 2008 series in a tight grid on a single wall. As a mural, it documents, represents, and also replicates a mausoleum and a social contract. Even now, his photos are devoid of people but never of life.

Richard Mosse ran at Jack Shainman through March 22, 2014, Richard Mosse and Yoan Capote through March 11, 2017. Juan Manuel Echavarría ran at Josée Bienvenu through through April 8, 2008, and April 12, 2017. Portions of these reviews first appeared in New York Photo Review and The Nomadic Journal.