The Red and the Black

John Haberin New York City

Ad Reinhardt: A Biography

Ad Reinhardt set himself high standards. "Purer and emptier," he wrote, and he pushed himself to some of the most demanding works of art ever made. His last paintings, before his death in 1967, may well look like large, uniform black squares—until the very moment one tries to turn away. Even then, they present only a grid three squares high and three squares wide. If the colors have names other than black, I do not have a vocabulary to describe them.

Michael Corris does have a vocabulary, but one that Reinhardt would never have recognized. Corris wants to make him all about words. He starts with Reinhardt's early political cartoons for New Masses, an American Marxist publication, from 1936 to 1946. He ends with Reinhardt's influence on conceptual art, and he sees continuities every step of the way.

His book, Ad Reinhardt, does the artist the favor of assuming that he meant everything he did. Yet it refuses to take him at his word. Its rambling, scattershot presentation skips over much of what Reinhardt painted and almost everything that he said. It also assimilates the paintings to the work of others, and it turns them on their head. "Art confused with life, nature, society, politics, religion," Reinhardt wrote, "is ugly." Despite its deep respect for the black paintings and a passion for recovering his early career, this book has an ugly view of art.

I have qualms about writing about it at all. The project found only a British publisher, in a dismally cheap production, without so much as running heads to help one find one's place—or to figure out which endnotes go with which chapter. Despite a preface by Dore Ashton, who has written often on the New York School, it seemed ready to vanish without critical reception and without a trace. I hate to help it gain attention. My only excuse is that the painter deserves the attention quite enough by himself.

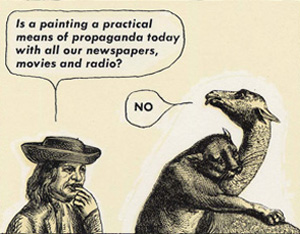

An expression of resistance

Ad Reinhardt was merciless with those who needed words. The Whitney has included him in "An Incomplete History of Protest" but he hated the reduction of art to politics, religion, or even secular morality tales. He derided artists and critics for their pretensions, their interpretations, and their accommodations to the marketplace. He mocked them in his writings and a blistering series of cartoons, How to Look at Modern Art. Others, taken in by the newfound success of modern art in American, took his title literally, he complained. He meant to satirize art movements and those who look at them, like William Powhida, Ward Shelley, and Jeffrey Beebe today.

He could also be patient—or just tired of complaining. He had, after all, kept at that series for a long time, returning to it after fifteen years, in 1961. "How do you feel," an interviewer asked, "about people who do interpret and explain" his paintings? "I'm a responsible artist and I give them no encouragement and they drop it after a while." Not this time.

Then again, maybe not ever. We interpreters and explainers are not likely to quit any time soon. Corris, for one, has been pursuing his project for some years, and it has the awkward feel of a reworked graduate thesis. Chapters tend to read independently or to veer off, and he devotes a full quarter of his length to younger artists—including a Scottish artist who knew Reinhardt's work only in reproduction and an Australian conceptual artist whom Reinhardt never knew. A full chapter and brief conclusion then return to the politics of painting. More than once, Corris laments that Reinhardt could not come around to his point of view.

The book runs only one-hundred fifty pages, plus an introduction and appendixes. It does not try for a cohesive monograph or a biography, and it is not out to supplant the classic by Lucy Lippard. It does not describe any paintings before the 1960s, and it does not reproduce any. (The estate denied permission.) It skips past a larger body of cartoons beyond New Masses—including those satires of art, first for P.M. (or, to be more thorough, starting as editor for an undergraduate publication at Columbia College) and later for Art News. It quotes surprisingly rarely from Reinhardt's writings, and it does not seek out testimony from friends and former students.

It does not mention the artist's childhood, marriage, postwar art studies at NYU, or teaching slots at Brooklyn College and Yale. Perhaps it takes him at his word: "I've never been called a good teacher, incidentally. I'm proud of that." Anyone who has caught a retrospective of Marlene Dumas, including Reinhardt's Daughter, will know at least one thing more than Corris's readers: Reinhardt had a daughter (although Dumas is, as usual, thinking of herself).

At its heart, however, the book makes a valiant effort. Corris claims to have tracked down four hundred cartoons for New Masses, including covers, under a variety of pseudonyms, although the biased statistic counts everything from pie charts to spot ads. He sees them as evidence of a lifelong political commitment, and he tries to relate that commitment to Reinhardt's paintings. "Between these two bodies of work—fine art and applied art, as Reinhardt would have said—there are remarkable conceptual and formal coincidences, strong enough and clear enough to argue for a formal link." Even more, he relates the cartoons to Reinhardt's integrity as an abstract artist. In the refusal to play along with the expectation of others, Corris sees "an expression of resistance."

Resistance to what?

But resistance to what? I have just quoted Corris out of context, in hope of a consistent answer: he speaks here only of "resistance directed principally at the politics of culture embodied by the New York School." He is quite honest in according Reinhardt his "sense of art's autonomy." He describes the black paintings as "seeing through to its bitter end the modernist process of negation through painting." He notes their "demonization . . . of the confusion of art and life," even as he makes that very confusion his thesis.

How, then, does one get from there to politics and back? I found it difficult to retrace his steps myself. He accepts Reinhardt's derision of political art, from prewar realism through Leon Golub and the Peace Tower in the 1960s. He describes Reinhardt's admiration for what André Malraux called the imaginary museum, a kind of precursor to today's virtual museum. There, Corris acknowledges, "the work of art is no longer seen as a reflection of its time and place." That alone would detach Reinhardt from any historical or contemporary agenda.

"It was really the quality of color in the abstract," Corris concedes, "that appealed to him—color drained of its meaning, color as pure quality, color as Platonic ideal." Here again, historical materialism does not seem at all relevant. Indeed, Marxists were struggling to make sense of its relevance, too. While the book describes New Masses as communist, it began as a response to the Worker's Party of America, and it went through much of the turmoil in American radicalism in those days, from the Hitler-Stalin pact through World War II. As for art, the pure quality of color did not take a position on Eastern Europe.

A superb section explains the process behind a black painting's subtle tones, in the thinning of oils. It alone makes the case for Corris as a student of Reinhardt and for what even this book calls "'art as art' and nothing else." Somehow, though, he desperately wants something else, but how? In answer, he claims both formal and conceptual parallels. Both take way too much verbal sleight of hand. They also take too many strange voices and even stranger silences.

As the most obvious trick, the book gives and then takes away—in the rhetoric of nevertheless. Chapters have quote after quote accurately representing the artist. And then, when one least expects it, they conclude with just the opposite. For all that has gone before, "The extreme nature of the 'black' paintings, the very way they 'work' in the world as art, contradicts their alleged dissociation from ideology." The contradiction itself counts as evidence: it, too, confirms that "Reinhardt did not diminish his pro-Soviet, anti-imperialist stance."

The idea is that negation implies difference—a point important to both Marxist dialectic and to Structuralist criticism at its best. Reinhardt's emptying of painting sets him at a remove from the compromises of other painters. But difference from what? To establish a political dimension of difference, Corris claims formal parallels between Reinhardt's commercial work and other pursuits that he kept strictly separate. That includes fine art on the one hand, Marxism on the other.

A worker by day

Born in 1913 in Buffalo of socialist parents, Reinhardt went to high school in Elmhurst. Another kid from Queens might have continued his commercial and professional training. He chose instead to study art history at Columbia while taking painting classes at Teacher's College. Thanks to Burgoyne Diller, the abstract painter, he worked for the Federal Arts Project (easel division) of the WPA right out of college in 1936. He also studied portraiture at the National Academy of Design before joining American Abstract Artists in 1937. He took on commercial work for such clients as Macy's and joined the Artist's Union of the CIO in 1937 as well.

From the first, then, Reinhardt sought outlets for his political, intellectual, and artistic commitments. I give more detail of his life and career than does Corris, who isolates his political illustrations. If one pounces on Reinhardt's radicalism as a fresh discovery, naturally it will weigh more heavily. Yet Lippard and others have long noted his work for New Masses and its support for the Communist Party's popular front. That still leaves the question of what his work as an illustrator means for his painting. In those days, Corris observes, he talked of a "free future" in the arts—but then what?

From the first, then, Reinhardt sought outlets for his political, intellectual, and artistic commitments. I give more detail of his life and career than does Corris, who isolates his political illustrations. If one pounces on Reinhardt's radicalism as a fresh discovery, naturally it will weigh more heavily. Yet Lippard and others have long noted his work for New Masses and its support for the Communist Party's popular front. That still leaves the question of what his work as an illustrator means for his painting. In those days, Corris observes, he talked of a "free future" in the arts—but then what?

For one answer, Corris looks to formal relationships between cartooning and fine art, particularly Cubism. Cartoonists mired in conventional illustration might have sought inspiration in anything from Daumier and late Goya to Victorian magazines. Reinhardt quickly seized on collage as a tool in composition and Ben Day tonal screens. In this way, he learned to "construct a work of art through a kind of destruction or ruin." Or did he?

Modern and postmodern art have had a wonderful interchange with commercial art. From the very first, Modernism dismantled the whole idea of fine art. It sought to express the machine age, quoted popular culture, and repaid its debts to both in spades. By the time Roy Lichtenstein mimics cartoons and Ben Day dots, art has a story worth telling. A direct line from commercial work to political does not tell it. Neither does a direct line from commercial work to abstract paintings by someone who, like Reinhardt, hated Pop Art.

Other parallels between the many sides of Reinhardt's career take even sillier reasoning. Corris cites Marx's ideal citizen—a worker by day and an artist in the evening. He cannot verify that this text, first published in 1932 in the Soviet Union, inspired Reinhardt. He notes that Reinhardt could have read The German Ideology in the original German, which is just to say that he could read German. My French does not exactly prove that I have read Montaigne, although I have tried, honest.

Even sillier, it would seem to prove that every artist stuck with a day job is living Marx's ideal future or is a closet Marxist. So, I am delighted to hear, am I. It would also seem to prove that, when Reinhardt could at last focus exclusively on painting and on parodies of the art world, he had repudiated political art. As Corris says, "Reinhardt did not come to political activism as a fine artist. Rather, he mobilized his considerable talents as an illustrator and cartoonist for the sake of his political beliefs." But how much did he have to give up for the sake of either one?

A program out of boredom

As his final strategy, Corris relies on seriously selective evidence, with excessive space for voices other than Reinhardt himself. The selectivity includes all that gets left out—the testimony of family, students, and his own writings. It includes the book's skipping past paintings before 1960 and the sheer weight of magazine illustrations after New Masses. Even mentioning P.M. would complicate things, by linking Reinhardt to a daily newspaper with a wider range of radical views, both for and against the Soviet Union. It would underscore that he left New Masses the year after the war, when a united front gave way to the Cold War.

It would underscore how much progressive and creative thought was associated with radicalism and indeed New Masses. It is no shame to say that Ernest Hemingway, too, contributed, but he had to say his farewell to arms. So did Dorothy Parker, and no one is going to treat all her light humor as a cover for propaganda. Robert Motherwell, who did not contribute, had his Elegy to the Spanish Republic. More than any of these, Reinhardt remained uncompromising in his politics, right through the Vietnam War protest movement. That still leaves just what it all meant for his art.

In public testimony, Reinhardt denied supporting Stalinism. Others dealt with the McCarthy era by lying, of course, and so perhaps did he. Still, the word communist does not appear once in his selected writings. The FBI files that Corris quotes have the obvious problem that the FBI dropped any case against the artist. "The sketches themselves," the FBI concluded, "did not have any communistic significance." Reinhardt is "not mentioned on any of the editorial pages as an art contributor."

More selective evidence appears in Reinhardt's own silences. Just when the book seems about to attribute strong views to the painter, it backs away—often without admitting it. Endnotes for his views on Communism cite nothing more specific than a history of Communism in America. An endnote on his correspondence with Thomas Merton, the seeker of spiritual perfection and a friend since college, supplies only a quote from Merton.

For the fullest statement of Reinhardt's views, Corris takes a 1936 essay by Meyer Schapiro. In "Public Use of Art," Schapiro argues that fine art should not take up the cause of politics. It could not radicalize ordinary people, because ordinary people could not care less about fine art. Besides, a "low-grade and infantile public art" already exists. Reinhardt studied with Schapiro as an undergraduate at Columbia. He must have known and agreed with that paper, but I should have liked some proof nonetheless.

The most egregious silence comes in the two chapters on Reinhardt's influence, where he vanishes almost entirely, while the author conducts lengthy interviews with that Australian artist. Most space of all goes to conceptual art, especially to Joseph Kosuth—not coincidentally, an influence on Corris. Further space goes to outlining the views of Lawrence Weiner, although the book also states that Reinhardt and Weiner did not speak highly of one another. Conversely, Yves Klein, who trademarked his single shade of blue, comes off as preoccupied with a painting's physical nature. This perversely makes Klein the formalist and Reinhardt's blackness the conceptual art. The artist who joked that he "finally made a program out of boredom" becomes engaged.

Let the social situation go

For all its weaknesses, the book has an important point. Reinhardt took everything seriously—politics, painting, and principles—and he saw no inconsistency in holding onto them all. He also had a sense of humor about them all, something that the book all but ignores. That irony may well have allowed the painter to realize how little he could control in his own legacy. "The first word of an artist," he wrote, "is against artists." He must have known that other artists could turn his art and words against him.

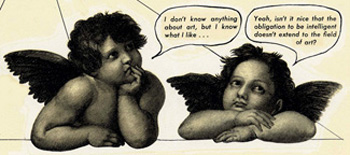

Reinhardt's mockery of the art scene sounds downright prescient amid today's celebrity artists, online gossip, global clients, rising and falling prices, and young artists turning against them all in drawings and cartoons. "My painting paints me," says one bubble in How to Look at Modern Art. "I'm a primitive," says another. "I don't know what I'm doing. Please buy my masterpieces anyway." He could not have predicted the industry surrounding art now, but he came close to describing it—and he had begun to influence any number of artists and interpretations even in his lifetime.

He knew perfectly well that he came out of the same mix of Modernism, humanism, and left-wing politics as the rest of Abstract Expressionism. Clement Greenberg had a leftist political agenda when he opposed avant-garde and kitsch. Schapiro may have disavowed public art, but he had his own claims for "The Humanity of Abstract Painting." Reinhardt must have known, too, how his formal development paralleled that of other artists. He could insist on silence, but other voices were always ready to speak.

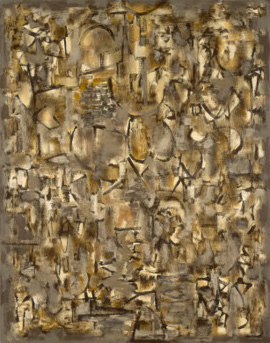

In a painting from 1947, taut curves and hatch marks on lighter brown push up against a painting's edge. Think of Paul Klee—or a cross between Jackson Pollock and stained glass. As Corris perceptively puts it, "For Reinhardt, gesture grew out of cartooning, calligraphy, and a study of Asian art." In this light, his overlapping white rectangles of 1951 can resemble tracery as well. The rectangles grow distinct and seem to sort themselves gradually into geometry as they turn in the 1950s to red and then to blue. In this sense, one really can look for formal continuity all the way from illustration to blackness.

Reinhardt's red, blue, and black paintings share fields of these colors with Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, as well as with black painting by Jake Berthot and in art today—and he did his best to distinguish himself from them all. The black paintings really do lead one everywhere from Minimalism to Op Art to conceptual art and back again—and to black painting today. Blackness may even suggest what Yve-Alain Bois has called the "debasement" in Pollock's drips and has linked to postmodern representations. Bois titles his introduction to Reinhardt's 1991 MoMA retrospective "The Limits of Almost." In the end, the black paintings may approach nonmeaning, but they are fated never to reach it, just as they never quite reach black.

He could not make the paintings any purer and emptier. He could not remove their Greek cross, for then oil on canvas would become conceptual art. He needed the painting's representation of itself, in its echoes of the object's edge, for it to sustain itself as nothing more than painting. He needed the human scale of his paintings, like his own outstretched arms, to keep them from representing anything human. Otherwise, they would become too large, like the Romantic sublime, or too small, like a collectible for the marketplace. "We have to face the fact," he wrote, "that the art work itself is the problem along with the artist and let the social situation go for a while"—but other problems, other social situations, other critics, and other biographers will always be waiting.

Michael Corris's Ad Reinhardt was published by Reaktion Books in 2008. Related reviews look at Reinhardt's black paintings and Reinhardt as curated by James Turrell.