The Body Politic

John Haberin New York City

Jimmie Durham, Cathy Wilkes, and Leon Golub

Groucho Marx would not join a club that would accept him as a member. Jimmie Durham feels the same way about citizenship in a nation.

It makes him by nature a skeptic. It has also kept his art little known in America, but not for lack of putting his body on the line. Skulls, flesh, broken appliances, and whatever else crosses his mind have landed on the walls or floor for all to see. All that could describe Cathy Wilkes as well, with an equally cryptic point of view. They could not have pleased Leon Golub, who knew the body as the locus of cruelty all too well. For Durham as a purported Native American, Wilkes as a working-class feminist, or Golub in his anger, is there more to politics than what William Butler Yeats called "the foul rag and bone shop of my heart"?

Join the club

When it comes to citizenship for Jimmie Durham, make that at least two nations, counting what Anglos might call a tribe. Born in 1940, Durham grew up in the American South but left for Geneva to study art. He showed in New York in the glory years of alternative spaces, but left again for Mexico and then Europe. By his own account the most prominent Native American artist, he gave up activism in 1973, and the Cherokee will not recognize him as their own. Either he could not document his ancestry, unlike Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, or he could not be bothered, even as the Brooklyn Museum rehangs its American wing with greater weight to Native American art and people of color. In each and every case, he never once looked back.

If it gets tiresome to keep track of his movements and affections, he embraces the charge. Wherever he goes, he says, he is the "center of the world"—and the Whitney adopts just that as the title of his retrospective. He might be there only in spirit, but he finds his spirit everywhere. He could not make it to the United States for the opening, but he does leave the polished branch of a "saved tree" to open the show and to mark its location. If it looks like a flagpole, it accompanies text art from 1992 labeling it an Anti-Flag. Try not to salute.

If something here sounds phony, he embraces that charge, too. His art boasts of its artifice, not least when it consists of pretend Native American art and artifacts. Even when he sets real animal skulls atop New York police barricades, they look like something left in the garbage. Maybe he hoped that they would join his 1982 Manhattan Festival of the Dead. He lived uptown in those years, not far from the Cathedral of John the Divine, which he revered as fake Gothic. Even when he displays what may or may not be his blood, he labels it "color enhanced."

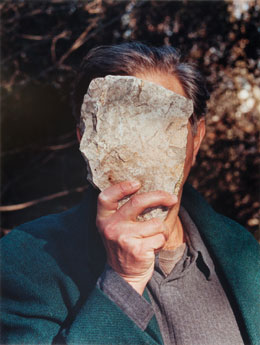

If he also sounds awfully self-involved, he would be the first to question himself, sincerely or not. His self-portrait looks like flayed skin, with a paper head and an opening onto his fragile heart. The penis of found plastic is anything but erect. He could be the consummate New Yorker after all, always doubting, always complaining, and always demanding that one listen. His Six Authentic Things include turquoise and obsidian, but also words. But then, as more text has it, "I forgot what I was going to say."

Durham is in constant dialogue with others, like Adriana Varejão drawing on images of Native Americans by past artists, Native American art in Brazil, Mary Sully in Modernism's New York, and Gabrielle l'Hirondelle Hill among native peoples in British Columbia, but he has scripted the voices, not least his own. Works on paper speak up for Caliban from The Tempest, and one can never doubt that he identifies with the ignoble savage. Another complains that he "made me without regard to his art career or I am sorry to say the sensitivity of the general art public," but soon enough he interrupts. The text on his largest work, from 2005, advises humility: "we worry . . . but the world has already moved on and has forgotten us." Do not believe that he has forgotten himself for one minute.

Those words precede an odd assortment of exhaust ducts, a spare tire, and dated electronics. Durham has some of the trash and macho of contemporary installations, some of today's identity politics, and a touch of outsider art as well—but the work's heart is appropriation as improv, with a debt to Robert Rauschenberg. His moose's head sprouts one antler like the wings of Rauschenberg's eagle, but with steel pipes in place of the other. Art as an ongoing experiment drew him in the 1990s to science, but again as sheer subjectivity or comedy. "Boy! Those are pretty colors, aren't they?" Yellow Higgs Transmitting Apparatus from 2013 sounds meaningful, but do not count on results.

He quit the American Indian Movement after just four years to make art, but he could not resist a dig at its leadership on the way out. One could accuse him of faux politics, much like his faux everything else. It can infuriate people, including me, and it has kept him on the margins, although he appeared in the 2014 Whitney Biennial—his first in decades. He plays the saint or sinner well enough, pounding an old refrigerator with stones, as if stoning Saint Stephen, but his "homages" have veered from Native Americans to artists of other races, like David Hammons and Alexander Calder. No doubt he would just as soon pay tribute to himself. Yet his work has at least one thing going for it, in its insistence of self-reference and artifice as inextricable from art.

Filthy looker

Cathy Wilkes may do more to stop the spread of colds than any artist ever. Her entire show seems designed to get visitors to wash their hands. Glassware lies here and there on the floor, as if left over from a sorry attempt to clean house, one item filthier than the next. Mothers tend to their children beside tubs caked with black. Or rather they tend to empty strollers, for children might have died of their sickly surroundings not so long ago. The dried sprigs here and there might have done them in.

Even the cheeriest displays come with an implicit warning not to touch. The rows of colored plastic belong to She's Pregnant Again, making them into a test of precious bodily fluids. Then, too, a leaden title like that one or Teenage Mother suggests that women have been touching or touched where at least one person does not belong. Even paintings look like fatal or accidental stains, in one case blood red. They look no more presentable than the worn curtains and fallen rags. The repeated urgings of museum guards to step back only reinforce the impression.

Not that trashy installations are anything new. Someone or something must have done in the stuffed goat in the most famous combine painting. Its maker, Robert Rauschenberg, also meticulously erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning, as if art needs a thorough cleaning. Not that filth is new either. What is The New York Earth Room by Walter de Maria but a roomful of dirt, with the Dia Foundation to pick up the tab? It also inspired The New York Dirty Room by Mike Bouchet and perhaps Edgar Calel. Nothing, though, can match Wilkes for her melancholy and repugnance.

The museum speaks of her range, including painting, drawing, sculpture, and found objects. In reality, her works divide roughly in two, between installations and modest paintings. The show intersperses them at that, as if the paintings fully belonged to the installations. The first use oil on nearly bare canvas for the faintest hints of a human presence in a landscape. The latter keep returning to people, as mannequins or stuffed fabric, in a living picture. A black woman leans over shards of hard to say what. Others with blunt, vacant, or pummeled features lean over a meager meal—not so far from the simpler scene of an empty table.

Just what, though, are they doing, and what would their bare faces and the canvases like to say? What would the dead TV here and the monitor there show if they worked? The curators, Peter Eleey and Margaret Aldredge-Diamond, do not gamble on an exhibition title. They speak of "abstract fables" and "rituals of life." They guess that the scenes of poverty derive from Scotland's industrial wastelands, although Wilkes is Irish and the scenes entirely domestic. They speak of "frail figures huddled on shore," even for coarse bodies behind curtains.

They may, though, be right about the rituals. People are giving birth and mourning, with faint hope of a life in between beyond the seeming ghost of a toy horse. Wilkes seems to allude most, too, to class and the fate of women. Feminists like Mika Rottenberg, Carolee Schneemann, Kathy Ruttenberg with her ceramic garden, and Brenda Goodman have long associated a woman's body with at once attraction and revulsion—as a matter of pride and as a critique of what men see. I cannot find enough in the exhibition even to dislike it, but I suspect that its true subject is art as dangerous and the site of looking. Wilkes is engaging the viewer as a filthy looker.

Taking art seriously

Leon Golub took painting seriously. He took it seriously enough to work it to the point of exhaustion—its own if not his as well. He took it seriously enough to look for imagery to the greatness of past centuries, in Titian, Francisco de Goya, and the Seleucid and pre-Columbian empires. He took it seriously enough, too, to apply them to issues of torture, oppression, racism, and war. For Golub, there is no longer time for knowing winks and pretty pictures: art is a matter of life and death.

That risks leaving it for dead, but he was risking everything he had. He was in his forties when he returned to the United States from France and Italy, joined the Artists and Writers Protest Group, and demanded that art confront apartheid, Central American dictators, and the war in Vietnam. He continued when others declared that painting is dead, right up to his death in 2004 at age eighty-two. His canvas is rough to the point of discomfort and worn to the bone, because he worked by adding paint, scraping or dissolving it away, and adding still more. Nothing else, he thought, could serve for the immediacy of his subject matter—scarred bodies, battered emotions, and damaged democracies. He looked to Titian for The Flaying of Marsyas, Francisco de Goya for The Disasters of War, and the Great Altar at Pergamon for The Battle of the Giants and the Gods.

Plainly Golub took himself seriously, too, and so do his supporters. A small survey at the Met Breuer centers on Gigantomachy II—a gift from the artist's foundation nearly ten feet tall and twenty-five feet across. Most of the rest comes from another promised gift, a single collector, and Golub's dealer. Of the large paintings, not one is on loan from a major museum.  Golub demands personal commitment, not public compromise. So, he would have said, do politics and art.

Golub demands personal commitment, not public compromise. So, he would have said, do politics and art.

The show's centerpiece, from 1966, displays his command of anatomy and foreshortening, along with his unnatural compression. Eight fighting nudes make it hard to know what fist belongs to what body, but without allowing anything so crude as chaos. While Golub may have entered the scene all at once, work from his years in Europe looks much the same only smaller. The one near-abstract canvas represents human skin after napalm. Late work admits brighter colors along with the color of worn flesh, and bodies sport faces, although their accusatory glances fail to meet. A house pet becomes a beast of the apocalypse.

Golub turned his back on abstraction much like Philip Guston, but without a trace of Guston's self-doubt and comic-book culture. He continued just when the "Pictures generation" apart perhapsfrom Andrew Topolski put politics on the table, but without the irony, identity politics, frank sexuality, or assault on art. His scale and gestures parallel Neo-Expressionism as well, but without the personal celebration of Georg Baselitz and Baselitz drawings. Golub had no room for doubt about anything and no patience for self-indulgence. He could not ask about a shared responsibility for history, like Anselm Kiefer, because he could not identify with a nation, not least his own. He never teased out specific events, not when he could turn them into myth.

The curator, Kelly Baum, calls the show "Raw Nerve." The title may suggest the nerves he touched or the nerve it took to touch them. Yet that very choice suggests the limits of an artist who never gets past what he claims to criticize. He is always one more macho combatant in a war zone, although the politics and style of his wife, Nancy Spero, who died in 2009, often merge with his own. Supporters can only justify strident or conservative painting on account of the politics—and simple-minded messages on account of his art. The trouble with taking painting so seriously is that, even at its most questioning, the questions answer themselves.

Jimmie Durham ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through January 28, 2018, Cathy Wilkes at MoMA PS1 through March 11, and Leon Golub at The Met Breuer through May 27.