Who Needs Men?

John Haberin New York City

The New Woman: Women in Photography

The Met pulls off something audacious—a history of modern photography. And it does so without a single man in the darkroom or behind the camera.

Of course, "audacious" can be just another word for stupid, but the show sure feels comprehensive. It spills out over the museum's three large rooms for photography and prints, into an adjacent nook often reserved for more focused shows—and to the rooms across the corridor, where anything goes. Its one hundred and twenty photographers have up to five works apiece and a history all their own. Does that have you worried about something else entirely than the absence of men? What holds the show together, and what might women photographers contribute or leave out? For the Met, they bring "The New Woman Behind the Camera."

On her own two feet

The show offers a sweeping history, and never mind about men. It begins in the 1920s, when art absorbed Dada, anti-art, and the shock of World War I and moved on. Photography declared its independence as an art form, even as magazine photography reached a growing public. Either way, photography need no longer imitate or defy painting. The show reaches to the 1950s, before a decade of trauma upset Modernism's certainties. Photography would soon be crossing Times Square with Diane Arbus and crossing America in all its diversity (to stick to women), but those stories are still to come.

It covers every genre of photography, from portraiture and fashion to photojournalism and experiment. Who could miss the men of early Soviet art when you can have Soviet posters by Valentina Kulagina and Elizaveta Ignatovich in that same brash black, white, and red? Who could miss the streets of Paris for Henri Cartier-Bresson when you can cross 14th Street with Rebecca Lepkoff and a Changing New York with Berenice Abbott? Who could miss Walker Evans when you can have Depression-era refugees for Dorothea Lange? Who could miss Man Ray and his photograms when you can have the ghostly traces of surgical equipment by Bernice Kolko or of jewelry Margaret De Patta?

Maybe you could, and so could I, but there are ample rewards for audacity. Dora Maar need no longer be just another mistress and just another footnote to Pablo Picasso, rather than a photographer who brought human intimacy to Surrealism. Lucia Moholy can speak for herself and the Bauhaus as her husband, László Moholy-Nagy, confronts the camera, open palm held out. She also exemplifies what a movement in Germany called its New Vision. Women were at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem with Lucy Ashjian, in World War II with Toni Frissell, and at the liberation of concentration camps with Lee Miller. They were working in color as far back as the 1930s, with Caroline Whiting.

As part of its 2020 "fall reveal," MoMA indulged in another act of recovery—a room for the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante in Brazil, with Dulce Carneiro a member in good standing. Her play of shadows recurs as Lola Alvarez Bravo looks out from a window as In Her Own Prison. It recurs, too, as Bravo faces baseball players through the dark horizontals of a stairwell, as if behind bars. The tension simultaneously formal beauty and foreboding could sum up Modernism all by itself. So is this the history of photography you know, with only the names changed? For an answer, the Met looks beyond the names.

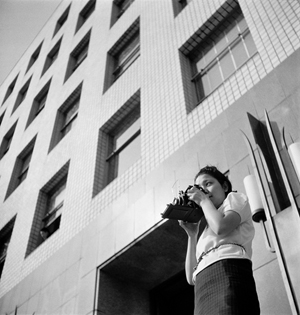

A photo of Tsuneko Sasamoto, a photographer in her own right in Japan, pictures her on her own two feet. She wields a slightly boxy camera, the kind that preceded the turn to smaller and more lightweight Leicas, with no trouble at all. She has a fitting backdrop in what might well have been her subject, too. She stands in front of a tall building, its grid all the clearer and more active in light of its odd angle to the ground. Have you ever tried to photograph a landmark, tilting your phone to capture it all—only to leave the building itself toppling over? Sasamoto's portraitist makes that a virtue and a given.

In a show of often unfamiliar names, that portraitist is simply unknown—and that, too, makes a statement. For one thing, it announces, you have a lot to learn. For another, you must learn not just from America, but from the world, with work from twenty countries. It will take recognizing women as photographers as well as subjects, starting with a room of self-portraits. It will take seeing them as more than flesh, with the only sordid detail, in a nude by Ilse Salberg, a man's. It will take getting to know the New Woman.

The good old new

The term originated in Ireland in the 1890s, caught on in England, and took on new resonance in America. It was still so alive that The New York Times used it to title a review of Joni Mitchell in the 1970s. It is a cliché, but a proud one.  Here it means a determination to step out from a woman's traditional role, with a studio of one's own. It can mean traveling in all the right artistic circles, and portrait subjects here include Jean Cocteau, Janet Flanner, André Malraux, Alban Berg, and Ethel Waters. It can mean projecting an image, too, so that fashion magazines are not a hindrance but a weapon.

Here it means a determination to step out from a woman's traditional role, with a studio of one's own. It can mean traveling in all the right artistic circles, and portrait subjects here include Jean Cocteau, Janet Flanner, André Malraux, Alban Berg, and Ethel Waters. It can mean projecting an image, too, so that fashion magazines are not a hindrance but a weapon.

For the Met, it also precludes a conventional history. Women here do not have an emerging, evolving image and aim, no more than Modernism or photography itself. The curators, Andrea Nelson of the National Gallery of Art in Washington with the Met's Mia Fineman and Virginia McBride, arrange work by genre and theme rather than chronology. If you want to know who was where when, forget it. If you want to know just who influenced whom, forget that, too. After all, an answer might involve men.

That has its drawbacks when it comes to defining a woman's art. Depending on where you enter, you plunge right into this genre or that, and things never let up. That may also have its drawbacks when it comes to the show's treasured diversity. Photographers from Latin America to Asia become subordinate to a western vision—of modern photography and the modern woman. It is just a step away from Abbott's overflowing newsstand in New York to commuters overflowing a trolley for Genevieve Naylor São in Brazil. Still, that uniformity, too, helps address the show's overriding question.

What, then, did women bring to photography, other than their heroism? For one thing, they told stories, and they listened. Lange shows a man leaning forward while his wife and son hold back. They hint at family and gender dynamics in terrible times. When she photographs an Asian American community in Oakland facing wartime prejudice, she lingers over a sign, in the first person, I Am an American. Boys for Helen Levitt take over an abandoned lot to play and to fight.

For another, they had their own image of women. Madame d'Ora photographs a woman painter dressed as a man. Nudes appear, with the formal elegance and wicked shadows of Irving Penn, but with lives of their own as well. When Grete Stern converts her dream girl into a lamp, with a man's heavy hand reaching across, she turns on the male gaze. When Germaine Krull photographs a nude leaning on one arm, she turns away. Could she, too, be the New Woman?

Are they, as the Met has it, liberated bodies? At the very least, they are women on the move. (Try not to mind that Olympic athletes for Leni Riefenstahl are Nazi propaganda, in frightening uniformity and as men.) Ilse Bing photographs a ballet called L'Errante (a woman wandering, sinning, or astray) and Lotte Jacobi a Spinning Top dance. Fashion models themselves take to the streets, in motion, for Frances McLaughlin-Gill. Florestine Perrault Collins, a black woman, had her own studio, but her portraits seem inert and dated by comparison.

Blindness and multiplicity

They are dismembering stories as well, including the Met's. The show runs by genre, but women photographers prove harder to pin down. Many appear in more than one section—like Margaret Bourke-White, with portraits but also a huddled line of African Americans seeking flood relief beneath a billboard boasting "no way but the American way." Frissell photographs the front in Italy, but also a bikini-clad model sunning on a Jamaican cliff. Krull turns up again with the Eiffel Tower and Stern with magazine photography and collage, in collaboration with Ellen Auerbach as ringl + pit. Her sardonic eye is unchanged.

Many more bridge genres. When they travel the world for a stricter "ethnographic approach," they lean to hair styles and portraiture. When they work in fashion and advertising, they remember the experiments. Gertrude Fehr has her solarized woman in profile, Trude Fleischmann her glamour in the shadows, and Olive Cotton her Teacup Ballet. Margaret Watkins has her near abstract soap and running water for "the skin you love to touch." Bourke-White returns with Fort Peck Dam in Montana, as a study in architectural form and a document of New Deal America. Tina Modotti photographs agricultural laborers in Mexico as a sea of hats.

They are disturbing old stories by looking and, once again, listening. In combat, Frissell listens to airmen behind the lines. In the camps, Miller sees the liberated as not emaciated bodies but celebrants, hanging an effigy of Hitler. In Hiroshima, Sasamoto sees not ruins but ordinary streets and the peace memorial that so intrigued Isamu Nogochi. And people are looking and listening back. They pack into café doorframes for São, intrigued by the camera.

In looking for unity, have I found an answer? It may lie in images of women, in a woman's body, or in bridging and disrupting genres, like self-portraiture for Brenda Goodman. Then again, that, too, adds up to a mess. It leaves so much more to pin down. I shall remember a typewriter for Modotti, a magnolia blossom for Imogen Cunningham, a bridge in flight or falling for Toshiko Okanoue, and workers at the New Uruguayan School of Architecture for Jeanne Mandello with their heads in the clouds. I shall remember a Jewish girl in London for Esther Bubley, alone in a boarding house but in safety and freedom—not for her conformity to my attempt at art history, but for herself.

Can something else, then, unify the answers to the search for unity? Self-portraits have a hand in them all. Many hold a camera, including Krull, Alma Lavenson, and Ilse Bing, doubling her image in a mirror. Others call attention to their role as a photographer by eluding the camera, like many in a collection of women photographers at MoMA. Wanda Wulz appears in cat whiskers, Mandello behind a veil of ribbons, Adele Gloria in snapshots in a spinning collage, and Annemarie Heinrich as her reflection in a sphere. Florence Henri sits facing more silvery spheres, behind a table that cuts her off at the waist as if stuck in the floor.

As an alternative, one can enjoy the chaos and forget the whole business of history. Audacity, too, has its blinders. A critic, Geoff Dyer, found the very essence of photography in blindness—and in a blind woman as seen by Paul Strand. Only Strand and you get to look on. At the Met, Lisette Model has a blind subject, too, but amid other pedestrians and other gazes. Here, too, a woman's art is multiplicity.

"The New Woman: Behind the Camera" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 3, 2021. A related review looks at the Helen Kornblum collection of women photographers at MoMA.