By the Book

John Haberin New York City

Jeanne Silverthorne and Chris Jones

Erica Baum and John Fyfe

When I think of art and literature, I think first of an artist's book. Artists, though, have other ways to bring a book to life, on the scale of a painting or a room. They also recall some of the language that shapes art even now.

Jeanne Silverthorne literally rewrites Frankenstein, but her installation has me quoting the madness at the heart of Jane Eyre. Her attic space comes on top of stacked rooms in assemblage by Chris Jones. Erica Baum and John Fyfe take their line and spatters as an extension of the human body,  but also of founding texts of Modernism, in poetry by Gertrude Stein and Guillaume Apollinaire. One does not have to enter debates over the difference between the visual arts and words—not when one can have both.

but also of founding texts of Modernism, in poetry by Gertrude Stein and Guillaume Apollinaire. One does not have to enter debates over the difference between the visual arts and words—not when one can have both.

In the attic

In the deep shade, at the farther end of the room, a figure ran backwards and forwards. What it was, whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight, tell. It takes well into Jane Eyre before Jane finally encounters the madwoman in the attic at Thornfield Hall, but one can catch a glimpse of her on the Lower East Side. Maybe not in person, for she may already have died in whatever has blackened the ornate chandelier that descends almost to the floor. Yet one can feel her presence in its mass or in the black cables that run every which way, backwards and forwards, across the floor. They no longer carry current to an exit sign or an odd light bulb lying here and there, but Jeanne Silverthorne still rescues them, as her installation has it, "From Darkness."

Silverthorne created the untitled sculpture, chandelier included, for her first solo show at McKee Gallery in 1994. Now, though, it has become part of more than one additional plot. The Morgan Library has been celebrating the two hundredth anniversary of Frankenstein as "It's Alive!" And she shares the terror and wonder with a further contribution, a black book with the novel's title in raised letters on its rubber cover. She has also handwritten an extended excerpt on more than two hundred pages in invisible ink. These are dark times, but one can more or less read them under black light.

I cannot swear that she has Jane Eyre in mind, too. Charlotte Brontë, after all, may well have meant her 1847 novel as an antidote to Mary Shelley's Gothic. Then, too, The Madwoman in the Attic, a feminist classic by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, asks to see roles for women in fiction beyond the angel and the devil—and so, I think, did Brontë all along. Still, her madwoman, Bertha Mason, has a dual parallel in Victor Frankenstein and his bestial creation, the lonely monster that drives him to the point of madness. Besides, Silverthorne adds a pair of fire extinguishers that might have rescued Mr. Rochester from Bertha's arson, just as Jane does halfway through the novel. They might have rescued him again from a second fire at the end—the one that consumes Bertha, blinds Rochester, and frees him at last to marry Jane.

If the connections sound intricate, so are the artist's lettering and cables. They also realize the room's potential as an attic. The gallery has grown since it introduced me to Charles Hinman in 2012, with shows now on every floor. (And here most gallery empires need several buildings to put on this many exhibitions.) First come Zlatan Vehabović, a Croatian artist who documents his residency in the Arctic, and Ulf Puder, a German who paints half destroyed modernist homes—with debts at once to Cubism, photorealism, Northern Romanticism, and self-indulgence. One reaches Silverthorne by way of other multilevel spaces at that, in sculpture by Chris Jones.

Jones makes assemblages that throw in everything but the kitchen sink. Make that including a kitchen sink, in miniature, along with the pipes and stills for bootleg liquor. His latest can still rest freestanding on a pedestal, like a burnt-out SLR camera with a view through its lens into a burnt-out landscape. Other new work, though, has gained in focus, as alternative lifestyles. They include an old-fashioned portrait gallery, a library with fine binding struck by lightning, the world's most abundant bodega, and a fantasy guitar collection along with the home brewery. They began as photographs of ordinary interiors but unfold over three or four chaotic floors.

They owe a good deal to Joseph Cornell boxes and to Pop Art, but even more to dreams that may never come true. Either way, they should have one thinking vertically on the way to the fourth floor. There Silverthorne, too, has a fondness for the evanescent, like a fly next to her Frankenstein. One keeps searching out the ends of the electric cables to see what may never come to life. More, though, her works are about what survives in the imagination or in a physical presence that will not go away. They cannot leave behind the darkness.

The line of a dress

A line just distinguishes it. As a patron and friend of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Gertrude Stein might well have been writing about their art. As a poet even in prose, whose work was never less than self-conscious and self-reflective, she was surely writing about that, too. She was, though, writing first and foremost about "A Long Dress." The poem appears Tender Buttons in 1914, where the tenderness extends to the line, the dress, and the woman who buttons it. It also inspires Erica Baum to pay close attention to the fabric and its making.

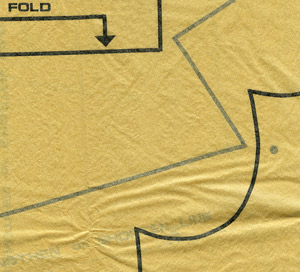

"What is the current that makes machinery," Stein began, "that makes it crackle, what is the current that presents a long line and a necessary waist." Baum's photographs crackle, but only by nurturing the silence of the seam in a dress or of a tailor's dummy. Stein did, after all, also write of "the serene length." As for machinery, Baum takes as her low-tech subject a manual for home sewing. She closes in on its pages, to see its seams as well. The tan and texture of its weathered paper might belong to a dress at that.

As a gay American in avant-garde Paris, Stein may seem an odd spokesperson for what men dismissed as a woman's work. And Baum, too, seems too sophisticated to dispense with a camera. She shows a model in a dress form only once, rather than closely cropped details of directions and design. Body parts appear only implicitly, in text. She hones in on their names in both French and English—for a more universal message or because Stein would have been hearing both languages every day. Yet gender for both women is front and center.

Stein dispenses with question marks, not to mention sentence structure, because what stands instead for material fact—or because everything for her is a question. Photography for Baum is similarly both questioning and a process art. She focuses on the manual's lines, curves, and arrows, with HEM or FOLD at once a descriptor and a command, and her photocollage adds rhythms of her own. She must have liked that Stein's poem also speaks of a modest range of colors, like further directions for photography. Both the writer and the artist are playful but serious. A teddy bear or rabbit serves as an additional dummy, but then so does the algebraic unknown of an X.

Stein dispenses with question marks, not to mention sentence structure, because what stands instead for material fact—or because everything for her is a question. Photography for Baum is similarly both questioning and a process art. She focuses on the manual's lines, curves, and arrows, with HEM or FOLD at once a descriptor and a command, and her photocollage adds rhythms of her own. She must have liked that Stein's poem also speaks of a modest range of colors, like further directions for photography. Both the writer and the artist are playful but serious. A teddy bear or rabbit serves as an additional dummy, but then so does the algebraic unknown of an X.

John Fyfe, too, finds his imagery in modern poetry and a devotion to line, like Archie Rand as well, but not in Paris. Guillaume Apollinaire wrote his Calligrammes on the front lines, where he suffered a shrapnel wound to his skull. One would hardly know it, though, from the exuberance of his words, which run wild to the point of abstraction. They do so literally as well, as a contribution to World War I in art. Lines about tears run down the page, handwritten and in French, while a reference to the world spreads out as if to encompass everything, making them even more of a challenge. Fyfe in turn uses them as source and overlay for his paintings.

Like Baum's, his rhythms derive closely from Picasso and Cubism, although in the stronger colors of Synthetic Cubism in its later years. Apollinaire in fact coined both Cubism and Surrealism, and his words might be a bridge between them, with the analytic instinct of one and the darker enigmas of the other. "Il pleut des voix de femmes," he writes, "comme si elles étaient mortes même dans le souvenir": it is raining the voice of women as if they were dead even to memory (perhaps a riff on "Il pleure dans mon coeur / Comme il pleut sur la ville," or "There are tears in my heart / As it rains on the town," by Paul Verlaine). Fyfe makes no particular effort to illustrate the text, but he still remembers. If Apollinaire's space between grammar and calligraphy was already a kind of book art, his paintings work best as a series, and I bet they would look almost as good as a catalog.

Jeanne Silverthorne and Chris Jones ran at Marc Straus through February 10, 2019, "It's Alive!" at The Morgan Library through January 27, Erica Baum at Bureau through February 17, and John Fyfe at Nathalie Karg through February 10.