10.27.25 — Feeling the Chill

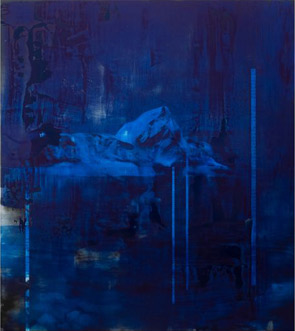

A dank chill has descended over painting everywhere since the pandemic, but nowhere so much as with Lorna Simpson at the Met. Just to enter black America through her latest art is to breathe the arctic air and to feel the arctic ice. It is to be up to one’s neck in crystal blue arctic waters.

The Met does not stick to Simpson’s Ice paintings, but the rest is no less bleak. Touches of yellow and those wide-open fields of blue cannot remove the weight of a meteorite descending from above or still more ice emerging from below. Their monotone grays do not compete with the touches of color, but rather add up to a single icy palette belonging equally to photographic prints, the artist, and life.  A young man and a glamorous woman wrap themselves in it for warmth. They have little choice. They wrap themselves in the mists and masses as well, through November 2.

A young man and a glamorous woman wrap themselves in it for warmth. They have little choice. They wrap themselves in the mists and masses as well, through November 2.

It is not quite their only recourse. That wet space beneath the heavens gets along just fine with a truly dry sense of humor. Simpson plays with the scale, drips, and black squares of abstract painting, to laugh at it like a proper Postmodernist, but also with it. Her Gradient and Special Characters series take the measure of violence in America, whatever the temperature. Black circles are at once bullet holes and the pattern on a polka-dot dress. The new African wing of the Met begins right outside, past a gift sheet, but it could be a continent away.

Simpson has put her sharp wit and deep feelings on display often enough before. Born in 1960, she had a Whitney retrospective in 2007, projects at the Brooklyn Museum in 2011, and regular shows at one of Chelsea’s poshest galleries. Is there really a need for more? The curator, Lauren Rosati, speaks of a more comprehensive show than any before it, but I am not so sure. Want to be the first to cover every stage of an artist’s career? Just wait until a little time has passed since her last show.

Not to confuse you with facts, but the Met has barely thirty works, most from a decade ending in 2021. It is no less timely for that. Where African American art used to mean African American history, scathing or supportive, recent shows have followed artists to Africa to recover a heritage. Simpson takes the logical next step. Why not leave the dark continent behind in favor of bright silkscreens and collage—and a hot continent in the midst of global warning for ice sheets? You can find a reality check in style magazines when you get home.

In fact, Simpson found her images and image makers in Ebony or Jet. That includes a woman with cat whiskers, a frisky smile, and a leopard-skin dress accompanied by a leopard with a wholly human smile. She turns stacks of those publications into sculpture as well, with a pretend ice cube beneath them. It may be a bit large for a drink and small for an iceberg, but The Titanic is safe. Just ignore the museum’s careerism in favor of its art. Simpson has what it takes to stay warm, the black community.

In fact, Simpson found her images and image makers in Ebony or Jet. That includes a woman with cat whiskers, a frisky smile, and a leopard-skin dress accompanied by a leopard with a wholly human smile. She turns stacks of those publications into sculpture as well, with a pretend ice cube beneath them. It may be a bit large for a drink and small for an iceberg, but The Titanic is safe. Just ignore the museum’s careerism in favor of its art. Simpson has what it takes to stay warm, the black community.

As I wrote after her retrospective, she refuses to play black artist while insisting on what the universal leaves out. Even now, as I wrote after her Brooklyn projects, she wears away at the boundary between the personal and the political (and you can follow the links to my past reviews for more). Her characters may talk, but they do not so easily communicate. They can let down their guard for a moment, but someone or something dangerous is about to interrupt, maybe the viewer. They can carry a tune, but it has to be easy to remember—or at least “Easy to Remember,” by Rogers and Hart. They can hum or whistle, but it is up to art to sing.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.