Are We There Yet?

John Haberin New York City

Young Picasso and Blaise Cendrars

It's Pablo-Matic: Picasso and Hannah Gadsby

Le Moulin de la Galette had never looked so popular, in art or in life. It is a wonder that a woman in the foreground has found a table—or the dancers have room to pair off. And yet a balcony remains empty and dark, and a gap has become visible at right, so forbidding that not even Pablo Picasso might have dared to cross.

Still, that woman's eyes engage the painter or viewer directly, and more than one dancer's eyes turn away from her partner to look out as well. Had they seen something in the charismatic stranger, or was he on to them all along? With "Young Picasso in Paris," the Guggenheim shows off a highlight of its collection and asks what it took for an outsider from Barcelona to make it anywhere and to make it new. More than a decade later,  a poet was still looking to modern art and Montmartre, the artist corner of Paris, to change everything. So are we there yet? More than century later, Blaise Cendrars still will not let go.

a poet was still looking to modern art and Montmartre, the artist corner of Paris, to change everything. So are we there yet? More than century later, Blaise Cendrars still will not let go.

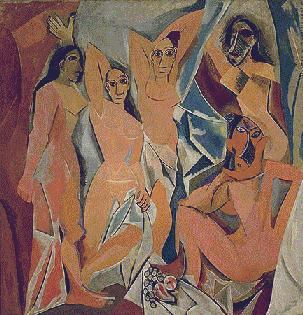

Ready for yet another show on the fiftieth anniversary of Picasso's death? Ready for yet another pairing of Picasso and recent art, as if there were someone somewhere that he has not influenced? If not, no need to worry, for "It's Pablo-Matic" at the Brooklyn Museum is different. It is a joke. More precisely, it is Picasso according to Hannah Gadsby, the Australian comedian, and her selection is (almost) all women. Now if only it, too, were not problematic.

Picasso the outsider

Picasso an outsider, seriously? Who more embodies modern art as an institution? Who is more accessible than Picasso in his Pink and Blue Periods—and who more dismissive than late Picasso in portrait after portrait of his lovers? Yet he did as much as anyone to identify art with the avant-garde, with women front and center. And the nineteen-year-old from Barcelona truly was a newcomer to Paris in 1900, haunting its café society, salons, and dance halls, like the Moulin de la Galette. The very name speaks of cheapness, in its origins as a mill with its end product brown bread, or galette.

The press, ever unable to resist a good story, has leapt at this one. France, it declares, distrusted tanned foreigners like him, although his painting of Bastille Day revels in the patchy blue, white, and red of patriotic crowds in the streets. And he did find a welcome, in Montmartre's Catalan and artistic communities—so much so that he stayed for months and returned for still longer the next year. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec favored the same nighttime haunts and encouraged him to try his hand, too, at posters. Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Vincent van Gogh painted Le Moulin de la Galette as well, and Picasso worked in direct response to them as well. Renoir's dappled sunlight becomes a sinister dance of artificial lights amid the darkness.

Besides, Paris embraced him from the moment he arrived. He came for the Exposition Universelle, a world's fair that just happened to include his work, and returned for a solo show with Ambroise Vollard, Modernism's greatest art dealer. On moving for good in 1904 he had no trouble finding other champions in Gertrude and Leo Stein. It seems only right that the Guggenheim's conservator, Julie Barten, turned up a friendly dog in Le Moulin de la Galette—and that Picasso painted over it. The curator, Megan Fontanella, also blows up a photo of the place, and the dance floor looked anything but confining until he set his hands to it. In a self-portrait, he turns up the collar of his winter coat, but he looks unconfined as well.

For Fontanella, Parisians played the outsider, too. Le Monde, or high society, shaded into the demimonde, or low life. Picasso himself makes it hard to distinguish partiers from prostitutes and fashion from sexual indiscretion. Which accounts for a woman's caked white makeup and the rouge smeared out below her eyes? A diner's white dress and accessories pile so high that one could mistake her for Big Bird. Her companion's black suit might itself be a disguise. Neither acknowledges the other.

Do they look inward, outward, or merely away? Their half-empty table holds out a spare meal, but with champagne. Picasso would have known many a meal like that himself. For all his success on arrival, he had a long way to go to dominate modern art. The Guggenheim has just ten works, including two quick sketches, as one of fifty shows in Europe and America on the fiftieth anniversary of his death. One can continue, though, to the next room, where its star painting usually hangs. The Thannhauser collection places him firmly at the turn of a century.

After "Young Picasso in Paris," its older painting looks more and more like his. One can recognize his poses in dancers by Edgar Degas, his bold women in Edouard Manet. Manet runs to flickering lights and darks, while Renoir dares to make Impressionism center on black. They can make Picasso look downright conservative. Then, too, he brought the facility of his drawing in black crayon. It took Cubism's turn against illusion to let him forget it.

The impatience of modern art

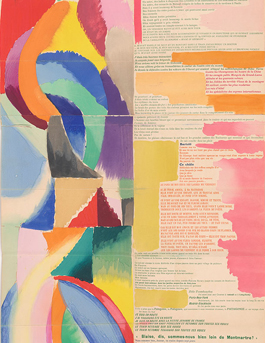

So are we there yet? After so many years, critics are still questioning Modernism's promise, but the questions were there from the start. As early as 1913, Blaise sounds like a child with a long trip ahead. Sommes-nous bien loin de Montmartre ("Are we really far from Montmartre") comes as a refrain in a poem that became a work of modern art itself. It unfolds as an accordion book, with watercolor by Sonia Delaunay, as "La Prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France." And now it hangs at the center of "Poetry Is Everything" at the Morgan Library.

In truth, Cendrars was not noted for patience. He sought to burn everything to the ground and to start again. Born Fréderic Louis Sauser in 1887, he chose a name with the sounds of blaze and cendres, French for ashes. "The guillotine," he declared, "is the master of plastic art," and he imagined living on la Rue de la Violence. How could his poem be prose? Easy, when art and the guillotine supply the "visual poetry."

How, too, can the Trans-Siberian Railroad, from Russia to China, end in Montmartre? For Cendrars, all roads lead to Paris. He collaborated with seemingly everyone on the road to abstraction, only starting with Delaunay (here called Delaunay-Terk). He brought his poetry to rhythmic circles of color from František Kupka, Morgan Russell, and Robert Delaunay, then Sonia's husband. He had an affinity as well with the mask-like faces of Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, the robotic bodies of Alexander Archipenko.  He sought out Marc Chagall floating over the rooftops and Fernand Léger, whose Eiffel Tower no longer has its feet on the ground.

He sought out Marc Chagall floating over the rooftops and Fernand Léger, whose Eiffel Tower no longer has its feet on the ground.

They all make an appearance at the Morgan. It is a modest show nonetheless, in the small gallery off the atrium. Not all of them illustrated Cendrars and his verses, and his name may not come to mind with the progenitors of modern poetry and art. Readers now are more likely to turn to another poet and his friend, Guillaume Apollinaire. En ce temps-là, his epic journey begins, j'étais en mon adolescence ("In those days, I was in my adolescence"), and one might hesitate at his immaturity, as did he, but modern art was in its adolescence, too, and it was an exciting time. He knew all the same les inquiétudes, les cendres, and la pluie qui tombe—the cares, the ashes, and the falling rain.

He took an interest in early cinema, too, once again to keep things moving toward a clean break. For him, the camera "sets itself in motion." His collaboration with Delaunay itself soars far out of reach. Most accordion books unfold horizontally, like that of Rick Barton a year before at the Morgan, so that they become part of the viewer's experience in time. This one hangs vertically, starting well overhead. You can hardly read much of it, not even if you know French.

The Morgan does not ask you to try. A video lets the poem play out in translation. Facing the work itself, you may be left only with that insistent refrain—and the art. Delaunay's clashing, compelling circles and triangles run parallel to the text at left, while blocks of watercolor fit between and alongside the words, like the marks of a censor in living color. They never quite obscure the text, in what the artist and poet called "the first simultaneous book," but then what more was there to refuse to say? Cendrars lived until 1961, but when you have burned everything to the ground, what is left?

Picasso's women?

"It's Pablo-Matic" never can know what to make of Pablo Picasso in America. Opening text has the worshipful but boastful tone of a museum. The show "acknowledges his transformative power" and indeed "contributes" to his influence. And then, just to the right, Gadsby's voice kicks in, much as in her comedy act, taking him down to size. Picasso's sexism and that very influence have held back women every since. One can hardly blame her and museum politics for competing voices and a contradiction that anyone can feel, but it is just not going away.

Gadsby herself contributes a credible copy after Picasso, but her eye is on something else again. This could be the impossible, crammed into the lobby gallery—a survey of women in fifty years of art. It ranges in approach from Joan Semmel with the awkward, inescapable woman's body to Mickalene Thomas with her pride and glitter, Cindy Sherman with the eye patch and villainy of a pirate, and Harmony Hammond transmuting them all into sculpture and abstraction. It appropriates the gloriously active mural right outside, by Cecily Brown, as just part of the show. Otherwise it stops short of contemporary art, but how better to confront Picasso with women than to start with what you know? And yet the contradictions keep kicking in.

For starters, they never do confront one another. A modest sample of Picasso hangs apart, without a major work in sight. His Vollard Suite of prints appears mostly because the Picasso Museum in Paris made it available. Women, in turn, hardly give him a second look. Nina Chanel Abney channels Edouard Manet and Olympia, Faith Ringgold Henri Matisse, Marilyn Minter Hollywood sex symbols, and Betty Tompkins the greatest woman artist of all, Artemisia Gentileschi. Guerilla Girls express their anger at art's exclusions of women with a poster after J. A. D. Ingres.

Then, too, they hold their fire at Picasso. Käthe Kollwitz recalls purchasing a work of his, Louise Bourgeois his 1939 retrospective at MoMA. For both, the discovery opened their way to art. Kiki Smith is "always learning" from him. The women I mentioned first simply go their own way. Either way, they have one asking whether one can separate the art from the man. Sherman in a quote insists on it.

By definition, that would mean moving on. It may not be possible, but the show still feels stuck in the past. It cites Linda Nochlin, whose "Women, Art, and Power" is still essential reading, but she was not the last feminist critic of Picasso. Museums that once excluded women now seek them out, like this one. Gadsby raises the influence on Picasso of the art of Africa and Oceanic art, but his "primitivism" is old news. So, too, is his sexism—and the ways that Picasso's women struggled against sexism.

Even there, though, art keeps asking for a second look. She herself she asks for one, of Picasso's women—a long look, long enough to see how a woman's neck and breasts have become a penis and balls. Does Picasso make everything about his desire, or does he anticipate the more fluid gender of art now? Maybe both, but all she can ask is what to say "when he couldn't even separate himself from his art." How about calling him an artist? News takes time, it seems, to reach Australia, but something may be lost along the way.

"Young Picasso in Paris" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through August 6, 2023, Blaise Cendrars at The Morgan Library through September 24, and "It's Pablo-Matic" at the Brooklyn Museum through September 24.