Hating the Art Fairs

John Haberin New York City

The 2012 New York Art Fairs II

Just when you thought the clamor of the art fairs had itself died down, there came a dramatic postscript. The first part of this article began the story, in the fury of a March weekend. However, May brought a British import, Frieze, and the Hamptons followed in summer—along with fresh debates over who hates them most. A postscript carries that love-hate relationship with big shows through the end of summer, with the Governors Island Art Fair.

Making fairs and making sausage

And you thought you had survived the art fairs. March came in like a lion, with a dozen of them, and you attended them all—or you had the sense not to.  But no, more likely you simply gave up in frustration, amid New York's many hundreds of galleries, wondering why it needed art fairs in the first place. Well, surprise, for the first weekend in May brings more, including the massive and massively upscale Frieze, on its first ever incursion from London. It sent nearly two hundred dealers to Randall's Island, best known for a passing glimpse as one crosses the Triborough (now Robert F. Kennedy) Bridge and for not being Riker's Island, with its prison. Can they all be longing for that fabled Russian oligarch, with little knowledge, bags of money, a boastful ego, and a desperate need for the cultured to take him seriously?

But no, more likely you simply gave up in frustration, amid New York's many hundreds of galleries, wondering why it needed art fairs in the first place. Well, surprise, for the first weekend in May brings more, including the massive and massively upscale Frieze, on its first ever incursion from London. It sent nearly two hundred dealers to Randall's Island, best known for a passing glimpse as one crosses the Triborough (now Robert F. Kennedy) Bridge and for not being Riker's Island, with its prison. Can they all be longing for that fabled Russian oligarch, with little knowledge, bags of money, a boastful ego, and a desperate need for the cultured to take him seriously?

Of course not, for they mostly lose money, gain modestly in contacts and publicity, and do it because they have to. Therein, too, lies a serious problem. As the business of art accelerates, the gap between many dealers and the world of artist collectives, open studios, and "do it yourself" grows—and both extremes suffer. One is bound to play it just a bit louder or safer, between installations and biennials, and the other will take pride in the familiar. All that only makes me embarrassed for enjoying the latest round of fairs, just as I often enjoy the shift in art from the age of the avant-garde toward diversity. In fact, I enjoyed feeling pampered, in exchange for my $40 (plus a small "fee") reservation, online only (for you sophisticates), to Frieze.

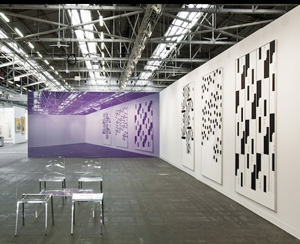

The free East River ferry from 35th Street sure has better seating than the one to Governors Island, not to mention a cash bar, and a shuttle bus runs from the subway in Harlem as well. Sculpture along the waterfront features charming abstraction with a jokey title from Ernesto Neto (I wanna bite you, Baby!), haunting songs over invisible speakers and an invisible string orchestra from Susan Philipsz (both with Tanya Bonakdar), neatly wrapped bricks from Rathin Barman (with an Indian dealer), and another promise from Tim Rollins and K.O.S. to teach kids about art. The temporary shelter, designed by the firm SO-IL and said to be the largest ever, has its six sections angled slightly from one another—creating natural gathering points, space for some of the city's more upscale cafés, and a more manageable experience. Its degree of natural light contrasts with the upscale chill of the Armory Show or the ADAA, as does a "Frame" section at its center for single-artist booths and a "Focus" aisle for presumably more affordable booths. Small as they are, one has to appreciate the occasional downtown dealer there, and some of their galleries are not much larger anyway. A few nonprofits appear elsewhere, too, as do John Ahearn's politically correct "South Bronx Hall of Fame," a full section for arts magazines, a Web site with art organized by price range, and a terrific bookstore.

As for the big players, a dealer like Andrea Rosen can put on a credible solo show for Elliot Hundley and still have ample space for more. Salon 94 can juxtapose a small bit crushed auto parts from John Chamberlain with an entire car, taken apart and distended at its middle by Liz Cohen. Mostly, though, old media and elegance reign—even or perhaps especially from galleries that one may associate with neo-Pop. A hefty square of mud from Italy (Arte Povera indeed) looks merely abstract, and Josh Tonsfeldt's painted wood with Simon Preston looks more aged than battered and neglected. Marble doors from Ai Weiwei in a London booth with Anish Kapoor seem yet another testimony to his grandeur, and it takes Europeans to display Sarah Sze or Barbara Kruger. In this context, her Too Big to Fail, in elegant black and white, comes off more as the title of a self-help book than politics.

It all looks so tidy that a robot vacuum cleaner, at a Dublin dealer, seems to be just doing its job—and I want to believe that it is part of Matt Sheridan Smith's art. One can even come away with a free copy of the Financial Times tailored to the fair. Naturally finances like these attract competitors, too. While Red Dot canceled at the last minute, NADA makes its first invasion from Miami in the former Dia:Chelsea. After the Independent there in March, it can also do a great deal to restore one's hope, even if the emphasis seems more on walls than on art. Free and approachable, it has labeled if closet-sized booths, more than half a dozen favorite Lower East Siders, Long Island City's SculptureCenter (with prints of past shows), and a dealer from the Bushwick-Queens border that I had first seen only weeks before.

Flaunting its own Miami connection, Pulse now delays its appearance from March, as does Verge. Pulse aims for the art fairs in miniature, with a separate floor in Chelsea's Metropolitan Pavilion for single-artist booths like a fine one for Peter Brock at Black & White, plus a few installations. Black glass tears and an African American hairdo from Fred Wilson may look awfully obvious, but what fun to see Risa Puno's two-player wood labyrinth game from Bushwick. Most of the art goes for clarity or restraint, despite a Dutch horse on plastic roller skates and the most tacky abstraction I shall ever see, in blood and resin, from a Williamsburg dealer I hesitate to name. Verge piles into Bleecker Street after the Brucennial, looking even more bedraggled and again with mostly self-sponsored artists, presumably on the verge as in "emerging" rather than throwing up. Back at Frieze, with Gavin Brown, Rirkrit Tiravanija serves up chrome sausages for a change rather than actual curry—and about the art fairs, as they say about sausage, sometimes it is better not to ask.

Are art fairs fair?

"I hate art fairs." I had barely walked into a downtown gallery when it emerged, without warning—and for once not from me. You can forgive me if I quote the man behind the desk, but not by name. After all, he may be in the Hamptons as I write, convincing buyers that it is the place to be. You can forgive him, too, if he complains. He has a point.

He had been setting up out there the previous day, with a long trip back to the city. Now, on a Saturday afternoon, he had the gallery to himself. Only moments before, someone had come in for a terrific summer show, with questions and a budding enthusiasm. If only the owner had been there, too, to help cultivate it. Years of hard work had brought staffing up to three, counting an assistant now and then, but it was tough going. And it took money.

He had been setting up out there the previous day, with a long trip back to the city. Now, on a Saturday afternoon, he had the gallery to himself. Only moments before, someone had come in for a terrific summer show, with questions and a budding enthusiasm. If only the owner had been there, too, to help cultivate it. Years of hard work had brought staffing up to three, counting an assistant now and then, but it was tough going. And it took money.

A weekend at the art fairs does not come cheap either, what with a booth, shipping, insurance, publicity, and maybe a clean shirt. The fairs also do not let up. Sure, they can earn a gallery greater visibility and sales. Not every traveler, between quick stops on the global circuit, scours the Lower East Side. Still, New York alone now has fairs in March and, starting with Frieze 2012, again in May, followed by eastern Long Island and then the Hudson Valley. Talk about diminishing returns.

Another dealer suspects different grounds for hatred entirely—and he really does mean the hatred of critics like me. On Facebook not long ago, he accused us of sheer self-interest: taking business straight to the buyer undermines our influence. I shall not name him either, as he deserves respect. He is a good reminder why artist collectives and DIY alone will never suffice. Even halfway decent dealers contribute through selecting, funding, marketing, and sheer commitment, and there are great ones.

He misses the point regardless. For one thing, the fairs contribute to the standards by which one looks at art—wrapped up in commerce and complicity. Bushwick dealers and open studios will be the first to tell him. But notice something else, too. The first to complain really are dealers, some of whom have nonetheless worked their way up from cheaper fairs to the ADAA or Armory Show. And, oddly enough, the last to complain are critics.

As a quick check online will show, they are almost unfailingly polite. By nature and profession, they enjoy the art and enjoy being a part of it, and they may fairly expect their coverage to bring them attention. They also think that they have influence. The Times pushed hard to give the Independent art fair its cachet, and in my own small way I have played advocate for the Moving Image (which my Facebook friend helped to create). I have also defended a former gallery owner, co-founder of Volta (which introduced the model of one-artist booths), and superb critic against conflict of interest. As for my beleaguered dealer behind the desk on Orchard Street, do not blame him if he was back on the phone the next minute, telling someone how much he looked forward to the Hamptons—and, you know what, part of him believes it.

Two's company . . .

With summer finally past, I can let you in on a dirty secret. I dread group shows, maybe even the Governors Island Art Fair. No, not attending them, not when one can watch as smart dealers let loose, try on artists and ideas for size, and sustain a few more weeks of midsummer madness. (Ever notice that, as art markets expand, a poor gallery worker's downtime shrinks a little more each year?) I mean writing about them. They bring out the worst in critics—and artists know it.

Aw, you say, so what? Sure, it means more work, having to keep straight all those contributors, when a lazy, pompous writer just wants to cast a cold eye and walk out. And plenty of shows have no more reason for being than a yard sale. And sure, artists and dealers are more thankful for reviews of a small show, since who can turn down sympathy and attention? Those who can would find yours truly a pretender anyway. But no, for decent art takes time, especially time with a single vision, while group shows can make a writer's job as easy as following a formula (and how appropriate that one 2012 summer show included a bed).

Artists resent formulas, and they should. Consider the alternatives—and then look back at old reports of art fairs, Biennials, Triennials, outdoor sculpture, and still other summer shows in your favorite newspaper, to see if you do not recognize them. Reviews can amount to a list, as dry as it is unrevealing. If press materials do their job right, a journalist comes home armed with one at that. They can amount conversely to a critic's picks, like half-remembered faces in a crowd. Take the faves in a Biennial ten year's back to see how well they hold up.

They can stick to the big picture, to the point of neglecting the art almost entirely. They can impose a theme that was not there, to claim yet another trend. One critic I admire fell in June for abstract painting, except that much of the work was neither painting nor abstract. Artists pounce most on the neglect, but even an overhasty compliment can sound like a dismissal. It only gets worse, I can attest personally, as one comes close to naming them all. Suddenly, leaving others out seems unfair to them, while adding still more names seems unfair to everyone.

In all these ways, a group show tilts a review from insight to judgment, whereas a critic contributes most by awakening your insights and your judgments. That is how the course of criticism from the bolder days of (say) Clement Greenberg, Meyer Schapiro, and Leo Steinberg—or a younger Lucy Lippard, Arthur C. Danto, Rosalind E. Krauss, and October magazine—has most let readers down. That is also is why reading about group shows is such a wonderfully guilty pleasure. You get your critical picks of the week, and you get to indulge in a story line all the more pleasurable for your knowing it is a lie. You can have your judgments, too, without the name calling, as with the late Robert Hughes, and without having to pretend that Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and big money stand for art.

Before I leave artists off the hook, notice that the weak critical alternatives correspond all too well to group shows themselves. Are there too many lists, too many egos, and too many attempts to include everyone? Faced with gallery artists, dumb themes, and everyone in sight with nothing in common, sometimes the only critical solution is to shut up. I truly admired the Governors Island Arts Fair, open weekends through September, with a hundred plus artists in at least as many rooms—and from painting and sculpture to elusive attic installations. Still, I gave up taking notes, especially without A/C. All one can do is to describe what one sees and to tell a decent story, or at least to try, and to try still harder even now swept away by fall.

Again, the 2012 New York art fairs ran March 8–10 and May 3–7. The Hamptons had at least three art fairs in the second half of July, NADA Hudson ran the weekend of July 28, and the Governors Island Art Fair each weekend in September. An accompanying article takes the story up through that first weekend, in March, and an update takes up Frieze, Art New York, and NADA. Other related reviews report on claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19 and a panel discussion of "Art Fairs: An Irresistible Force?" And do not forget the 2021 art fairs, spring 2022 art fairs, fall 2022 art fairs, spring 2023 art fairs, and fall 2023 art fairs yet to come.