A Bare-Bones Biennial

John Haberin New York City

The 2012 Whitney Biennial

Is it time to give up on the Whitney Biennial? Some demanded it, right as it set to open, but guess what? In a very real sense, the 2012 Whitney Biennial already has.

Oh, sure, the exhibition is not going away any time soon, and neither is the attention that drives it. On a Saturday around noon, the line out front snaked around the corner on Madison Avenue, and the basement restaurant, Untitled, drew a crowd as well. Can the Whitney still get people talking quite the same way, though? Is it out and out refusing to try? Rather than define the state of American art, it seems content to stir things up around the edges, with the sparest and, often as not, most cryptic selection ever. And not a bad thing, too—but first and last a word about those demands, competition from a "Brucennial," and a Biennial's place in the scene.

Is this it?

People always come to a Biennial with questions. What is the state of American art, and is this it? Who will make the cut, and who will be left out? These questions get people upset, because they frame inclusions and exclusions in terms of institutional power, and Biennials can assert that power in one of two ways. They can claim to have it all, or they can stake a point of view. One of this year's curators, the Whitney's Elisabeth Sussman, sure had one in 1993, a stridently political Biennial that angered pretty much everyone.

Well, surprise. The 2012 Biennial is themeless, but she and Jay Sanders, a freelance curator, pick just fifty-one artists, many of them young. And that includes films by Charles Atlas, Frederick Wiseman, and the late Mike Kelley (to name just three) that a day's visitor might never see. It includes surrendering most of the fourth floor to performances that may take weeks to change. It includes a performance up in the fifth-floor mezzanine by Georgia Sagri, consisting often as not of her refusal to show up at all, amid a virtual studio of pillows, doors, empty clothes, and museum reproductions. Red Krayola, a rock band from the 1960s that I somehow overlooked, show up mostly by Skype in front of an immense guest book, while Andrea Fraser contributes only an essay—in a display copy of the catalog that the guard must chide someone every minute or two for attempting to read.

On opening day, Sarah Michelson turned the main performance space into the diagram of a residential and business complex, on which one woman paced in a horse's head, while another diligently and pointlessly scrubbed the floor. Two weeks later, dancers had adopted a more limber and synchronized choreography. Around the back Michelson's "dressing room" displays clothes and hair care that visitors may not touch. A floor below, Dawn Kasper stars in a homeless pack rat's mobile studio. There she can hardly stop chatting up visitors, like the anti-Marina Abramovic. As Fraser titles her own essay, "There's No Place Like Home."

Elsewhere, one might notice most the silences. They start upstairs, where Lucy Raven displays TV test patterns alongside a player piano. Its scheduled bursts of sound have, so far, eluded me. They extend to Lutz Bacher's dismembered organ, its pipes in a pyramid like a squat and dysfunctional Mark di Suvero. They extend to the empty maze of a two-story house off the lobby, by Oscar Tuazon, and the empty shed in the sculpture court, converted from a dumpster to an education center. Every so often, K8 Hardy promises to use the first for a fashion runway, with or without (well, okay) her trademark afro and pink skin.

All that leaves precious little space for painting or sculpture. Part of the first comes with selections from the museum itself, in a mock period room by Nick Mauss. On opening hour, its two doors facing the elevator were shut, without credit yet to Mauss. Faced with the seeming blank wall but for a painting by Marsden Hartley, who died in 1943, an online arts magazine included Hartley among the Biennial artists. More painting comes in a room of Forrest Bess, who died in 1977, curated by Robert Gober. Speaking of a museum's influence in a commercial art world, Fraser writes, "It is not only the immaterial character of art discourse that predisposes it to this function and mode of operation"—but hey, it can hardly help.

All that leaves even less space for contemporary American art, or at least it stretches the definition as much as possible. I still think of Jutta Koether and Kai Althoff as German, although the first also made the 2006 Whitney Biennial, and both now live much of the year in New York. Koether bases her The Four Seasons on Nicolas Poussin, a garden in sunlight, and an old-world passage from innocence to ripeness and fall. Althoff paints people torn between claustrophobia and stylish society in the style of Paul Gauguin. Gisèle Vienne, a French-Austrian choreographer who has collaborated with Dennis Cooper, directs a multinational team in a dark vision of the American impulse—an animatronic blond male teen holding an animal puppet and a sullen stare. And the one film running the entire exhibition examines a minor late Mannerist and early Baroque artist, Hercules Seghers, thanks to Werner Herzog.

Children of modernity

This is maddening, but it is not altogether mad. Globalization is real, as in the harsh seas of film for James Benning and Peter Hutton, and Biennials have recognized it for ten years now. So is the recession, adding to the backlash against huge Biennials and a gradual downsizing in the last three, and so is the interest in performance. Together, they suggest a Biennial nurturing the edges of New York art, and often enough it delivers. For the first time in memory, one can leave provoked rather than overwhelmed. The show may lack a theme, but it does have a point of view, the kind that gets one thinking and arguing back.

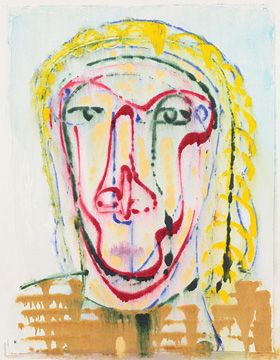

For one thing, fewer artists allows them greater focus and more work. The two most prominent painters, Nicole Eisenman and Andrew Masullo, each get two walls—the first for her faces that exploit the clumsiness of outsider art, the second for his abstractions not all that far from Bess's. Richard Hawkins gets three walls for his collages of fine art and personal annotations. For another thing, performance and architecture signal an interest in art that crosses media without descending into bloated installation. Sam Lewitt makes abstraction from magnetic fluids and Liz Deschenes from a process closer still to photographic exposure. Elaine Reichek creates paintings from weavings, like Sheila Hicks, another bow to folk and decorative arts, while Vincent Fecteau's sculpture looks at first glance like piled fabric.

For another thing, the installation takes the measure of the museum, just as with performance. It may scatter an artist across several floors, as with tiny constellations from Bacher and hand-painted slides by Luther Price, like twin celestial maps of the Biennial. More often, it can trick works into running together. That happens with Sagri's room and Red Krayola's open book. A wall of thread by Cameron Crawford, like white bedsprings, could serve as a loom for Reichek's mythic Ariadne. Kate Levant's Detroit memories that anticipate the pressure on art in Detroit and the Detroit Institute of Arts and its collection today, like walls gutted to traces of installation, blend into Tom Thayer's silhouetted and standing cranes, portable turntables, and old PCs.

The work adds up to a strong point of view politically as well. Michelson's dressing room, Hardy's fashions, Reichek's weavings, and photographs of family and protesting hospital workers by LaToya Ruby Frazier all carry feminist import. Mauss's and Gober's curatorial ploys both deal with homosexuality and gender. Forrest Bess mutilated himself in search of transgender identity, with the grisly evidence on display, too, and Wu Tsang recreates a Latino LGBT lounge from East LA as a pit stop. And this opens up the Biennial's problems as well. If this show were any more fashionable and politically correct, it would sink like a stone.

What seemed so exciting and liberating seemed on my second visit predictable, confining, humorless, and obscure. The Biennial brings in new galleries, including at least two from the Lower East Side, but trendy ones nonetheless—and critics have pounced on Sander's inclusion of Greene Naftali, where he has played a role. The outsider and expressionist impulse might be tailor-made for a review in The Times. Matt Hoyt's handmade relics and Michael E. Smith's oatmeal-crusted basketball share a retro fixation with Price's slides, Raven's test patterns, and Thayer's turntables. As with his study of cave painting, Herzog's close-ups may be static or ravishing, but I do not for a minute believe that Seghers in Amsterdam was the "father of modernity in art." When Joanna Malinowski hangs around with her dog or builds a bottle track out of fake bison tusks, is she really turning Joseph Beuys and Marcel Duchamp into Native American rituals?

Maybe not, and more power to her—and to a bare-bones Biennial. From Madison Avenue to the Lower East Side, one can start to see the children of modernity, and some of them may have a sense of craft and a sense of humor left. As it happens, the political themes of the 1993 Biennial look sillier than ever in retrospect, but its choice of artists looks a lot better. Several, like Atlas and Gober, turn up this time, too. Could the same dynamic be happening again, and could my first impression have been right after all? Think ahead to the demands on the next Biennial.

Banning the Biennial

As this Biennial opened, a curious petition circulated: ban the 2014 Whitney Biennial. As unfocused debates go, credit this one for planning ahead. While another group was protesting the museum's acceptance of funding from Sotheby's, in light of the low status of art handlers, the petition never once mentioned the issue or even called for a boycott now, in 2012. The whole question sounds more like proxy for simmering resentment of how wealth shapes careers and reputations. One may as well call to shut down half of Chelsea—or to stop MoMA's collecting contemporary art and, at long last, more women.

People have joked about "the show one loves to hate" for so long that it is hard to muster the energy to hate it. It is harder still to expect to promote rising artists by reducing their chances to exhibit. One could even argue that the Whitney is not endorsing Sotheby's, that the auction house might as well do some good on the side while starving its staff, that museums can hardly compete with the 2012 New York art fairs for crass commercialism, and that gallery workers hardly make out any better than the auction staff. The Whitney genuinely wants to expand the scope and to raise the public profile of art today. And the outcry sounds dated in another way, too. The Biennial is no longer the show one loves to hate, because it is no longer the show.

For one thing, it is no longer one show. Rather than defining the moment, each version over the last twenty years has all but started anew, from angry and political to in turn as sprawling, flashy, muddled, and exclusive as the run-up to the Great Recession—and now open, impulsive, critical, and performance based. It also now has to compete with a New Museum Triennial, at least two five-year museum shows of emerging artists, and several hundred galleries that did not even exist not so very long ago. It faces alternatives in pop-up spaces, DIY and artist collectives, Long Island City, Governors Island, the Brooklyn waterfront, Bushwick open studios, and unending art fairs. It has incorporated its own critics, like the Bruce High Quality Foundation, with a white hearse for, presumably, the death of art in the 2010 Whitney Biennial or the dead artists in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. And then there is the latter's "Brucennial."

For one thing, it is no longer one show. Rather than defining the moment, each version over the last twenty years has all but started anew, from angry and political to in turn as sprawling, flashy, muddled, and exclusive as the run-up to the Great Recession—and now open, impulsive, critical, and performance based. It also now has to compete with a New Museum Triennial, at least two five-year museum shows of emerging artists, and several hundred galleries that did not even exist not so very long ago. It faces alternatives in pop-up spaces, DIY and artist collectives, Long Island City, Governors Island, the Brooklyn waterfront, Bushwick open studios, and unending art fairs. It has incorporated its own critics, like the Bruce High Quality Foundation, with a white hearse for, presumably, the death of art in the 2010 Whitney Biennial or the dead artists in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. And then there is the latter's "Brucennial."

As for the Bruces, those tricksters have staged their own alternative for three years now—this year, in a big box with mezzanines above and below on Bleecker near Thompson Street (also the site of the Verge art fair coming up in May). The almost four hundred artists include such exclusive names as Damien Hirst, but do not look too hard for them. I imagine the Bruces faked one of his dot paintings, already about as fake as art gets. I found myself wondering if they had in fact faked everything, just in case anyone is still paying attention. Their past work has, after all, depicted the art exhibition as an empty classroom and the art public as the zombie audience for a zombie film. No wonder the "Brucennial" draws a willing crowd.

Is it really an "alternative"? In bulk, one has the pure pleasure of visual overkill, but unknown artists can hardly benefit. Nor do they make much of an effort, with casual realism and sloppy abstraction that look straight out of a forgettable show from decades past. Sure, everything old is new again, but can Salon hanging with art to match really democratize Modernism? It runs almost exclusively to painting, give or take a handful of equally old-fashioned sculptures and a video that captures visitors in, naturally enough, time delay.

Maybe it is about time to update the old institutional critique of art for today. The critique goes back to a time, to when the Museum of Modern Art could and did define the canon, with the added irony that Ad Reinhardt mocked the connections before anyone else. It goes back to the Frankfurt school, who proposed a remedy in Marxist theory, a stern formalism, and dismantling the very idea of authenticity. They got their wishes, too, but the influence of money only grew. Since then, art has found a broader public but nowhere near the public for music or film, placing it more and more in an uneasy spot between high and popular culture. It has achieved the promise of diversity, but also the pressures of a market economy—and I look forward to more critics, curators, and, yes, Biennials ready to look hard at both.

The 2012 Whitney Biennial ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through May 27, 2012, the "Brucennial" through April 20 at 159 Bleecker Street. Other reviews look ahead to the 2014 Biennial, 2017 Biennial, 2019 Biennial, 2022 Biennial, and 2024 Biennial—or back to the 1993 Biennial, 1997 Biennial, 2000 Biennial, 2002 Biennial, 2004 Biennial, 2006 Biennial, 2008 Biennial, and 2010 Biennial.