Zen and the Art of Minimalism

John Haberin New York City

Requiem for the Sun: Mono-ha

Just Knocked Out: Lara Favaretto

Minimalism came to New York with the sudden impact of flung molten lead. It defied not just Abstract Expressionism, but a preindustrial past. It offered not a prayer but a demand.

Yet Minimalism had an Asian parallel, in Mono-ha. Last year, the Guggenheim introduced many Americans to one of its exponents, Lee Ufan. Now a Chelsea survey puts him in perspective. It tempts one to see a traditional Japanese art of Minimalism.

Although stripped down a bit from a version at Blum and Poe in LA, "Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha" has eight artists and three floors. With big work and documentary photos, Barbara Gladstone stresses a movement, as a signal achievement and as a work in progress. It even comes with less ponderous philosophizing. As it happens, artists are still trying to compete with western models on the scale of a museum. Lara Favaretto, a child of the nation that invented another parallel in Arte Povera, at PS 1 should know. Can one still seek, then, a uniquely Japanese art?

Back to the garden

One might see something special in its materials, like water, stone, and hempen paper. It prefers rough timbers to the polished boxes of Don Judd—and incandescent bulbs to the fluorescent light fixtures of Dan Flavin and François Morellet, even before environmentalists and environmental art would wish them obsolete. It accepts transience, and almost every work here is a reconstruction from a decade's worth, although mostly from a single year leading into 1970. Noboru Takayama's Headless Scenery captures the moment on blurry film, with a clock in reverse, as if rolling back time. One might have Zen and the art not of motorcycle maintenance, but of household wiring. Nothing here is out of place indoors, but a first-time visitor may still come in search of the garden.

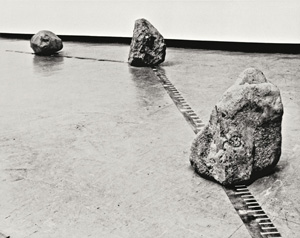

One had better look hard. A Japanese garden needs a stone, and Susumu Koshimizu's Paper neither hides nor fully encloses a large block of granite. It dominates the gallery's largest space, with two shades of off-white—but also like an oversized cigarette box. A large black cylinder, Nobuo Sekine's Phase of Nothingness, might be a well, and his broad platform perhaps a foot high might be a reflecting pool. One can guess at water and, hoping no one is looking, blow on its polished surface to see. Then again, the blackness still has mass and sheen.

A garden needs something soft, like vegetation, and something tall, like a tree. Katsuro Yoshida's long cylinder might represent a fallen tree, but then the cotton bulging out from either end would have to be tree rot. Alternatively, it could work as an irrigation pipe for the garden, but that, too, is an illusion. Yoshida pieces the metal together like homemade clothing, the seams showing. East had met west long before, in Isamu Noguchi and the Noguchi garden museum. But this comes after Modernism, when a meeting is no longer a unity.

One need not worry anyway about losing one's religion. Most Japanese do not profess one. Mono-ha, meaning "school of things," could be a direct rejoinder to Shinto, the "way of the gods." "Requiem for the Sun" sounds more an allusion to militarism and empire, whether as fond memory or a clear insistence on its death. Indeed, the youngest artist was one year old at the end of World War II, the oldest maybe nine. Japan has its own history, what MoMA labels "Tokyo: The New Avant-Garde," and Mono-ha differs from simply a global Minimalism even without the garden, much as for Yun Hyong-keun in Korea.

For one thing, the artists often work with similar arrangements of similar materials and even similar titles, to the point that one cannot easily say who made what. Takayama sets four railroad ties in a square, one end of each poised on the next. Three more ties lean from within the square against the wall. Lee Ufan leans his own beams and scattered large paper sheets to the wind as well. Contrast that with signature materials like Flavin's lights or floor tiles for Carl Andre—or, for that matter, actual flung lead by Richard Serra.

For another, this art embraces paradox and transience. Kishio Suga creates four walls of uncanny whiteness, less than shoulder high, surrounding a slightly taller and more massive pedestal. Regular indents give the illusion of blocks of resin that somehow spilled and shattered at their edges, leaving drippings and scraps of the actual wax on the floor. Koshimizu explicitly marks space and time. He hangs a small brass cone from fishing wire, its point just above the ground, as ambiguously plumb line and pendulum. Takayama's square of railroad ties is in infinite descent, like Piranesi stairs or an Escher fountain.

Minimalism as illusion

Along with transience comes instability—or at least its threat. Sekine has another plate of black steel, this time resting waist high on a white sponge that bulges outward from the weight. The title, Phase, even sounds on its way to something else. Yoshida's suspends a wood beam at an angle from the ceiling. The rope looped around it continues down to a stone that provides at once contrast and anchor for the beam's single point touching the floor. Sekine also suspends a smaller rock from a bump in white cloth on the wall, the workings manifestly hidden and visible.

Along with illusion, then, comes the possibility of the hidden. It also violates a cardinal rule of Minimalism, although Jasper Johns articulated it first: what you see is what you get. Jiro Takamatsu hides a light bulb behind a steel board, just under three feet long. In person, it makes a clean contrast between object and space, visible and hidden. In reproduction, I noticed first the whiteness of stainless steel and the glare of light, spreading upward, cast against the wall.

Yoshida has an even more striking disjunction between object and reproduction, now and then. He wraps another beam in a black electrical cord that continues to a light bulb also resting on the floor. In person, I saw the contrast between openness and tentative containment, gravity and light.  In jpeg the light came to me like the flame at the end of a fuse, waiting to burn through to the wood and then to explode. Ufan himself plays similarly with a light bulb, cord, and stone, but less explosively. The show's photographs provide a further reminder of the gap between movement and memory after forty years.

In jpeg the light came to me like the flame at the end of a fuse, waiting to burn through to the wood and then to explode. Ufan himself plays similarly with a light bulb, cord, and stone, but less explosively. The show's photographs provide a further reminder of the gap between movement and memory after forty years.

For all that, these are objects, art objects—another difference between Mono-ha and Minimalism. For all the drama, Mono-ha lacks what Michael Fried called theater, meaning the gallery as a stage set for the viewer. Sekine's sponge resembles a biomorphic carving—created, self-creating, and the illusion of intention. One stays apart from the work, for safety's sake alone. Maybe Serra comes closest, with his Prop Piece, but one can enter even the scariest Tilted Arc, along with one's perceptions. One is also not likely to mistake it for an older ideal of sculpture as fine art.

Parallels to the west come easily nonetheless. The Japanese artists were born between 1936 and 1944, Andre in 1935, Flavin in 1933. Flavin, who collected Hudson River School drawings, had his own love of light and landscape. Koshimizu's worn paper parallels Arte Povera, in Italy, as does Koji Enokura's leather triangle set against a corner as a pyramid. Its torn, mottled light brown surface recalls a sliced canvas by Lucas Samaras. Sekine's cylinder even has a counterpart in Iván Navarro's 2012 brick well, which mirrors in infinite regress the word ECHO.

Ufan's six small, black L-shaped sheets look so minimal that they come as a relief, like a loan from Sol LeWitt. Even so, two serve as corner pieces, redoubling the architecture, with the other four freestanding—as if the four corners of the room had broken off and created a second gallery in miniature. To one trained on late Modernism, Mono-ha can seem pretentious and precious. To one trained on Mono-ha, I suppose, American art might seem ego-driven and simplistic, based on axioms that lead to contradictions just waiting to become art. Either way, after so many installations and the revival of everyday objects in art as a kind of Neo-Minimalism or rebuilding Minimalism, a decade once dismissed as formalism looks more relevant than ever.

Minimalism as self-involved

Lara Favaretto was four years old in northern Italy in 1977, when Walter de Maria brought his earth art to Soho, and she approaches him like an impatient child. His New York Earth Room, now the city's lonely outpost of Dia:Beacon, still fills a gallery. Its visible architecture, past a pillar and the turn of a wall, becomes an expanse that no visitor can enter. Favaretto, in contrast, welcomes walkers, who may find her black soil surprisingly hard packed. In fact, they cannot get past the dull rectangle to the dull rest of her show at MoMA PS1 without crossing it. They also may imagine a certain smell sticking with them for some time.

Favaretto approaches much of high Modernism the same way. A cube after Tony Smith has a little too much of its green confetti on top, with the rest slowly peeling off onto the floor. The steel plate of Showing Off looks more scavenged than Carl Andre would allow, and its dents allow blue silk to show through. She goes about "entombing" a painting in white yarn, almost the size and shape of a Jackson Pollock, mimicking and mocking his formalism and masculinity—not to mention Robert Ryman and white on white. Pipes overhead accompany one through the exhibition, titled "Just Knocked Out," competing with one's own mental map of the space. Their placement and touches of color derive, she insists, from Piet Mondrian.

She hardly means anything new. Her video of an eraser bouncing off walls picks up everything from Richard Serra flinging lead to claustrophobic corners in Bruce Nauman. Bill Bollinger back then had his own indoor soil covering, Alighiero Boetti and Arte Povera had their classy poverty, and Mike Bouchet already mocked them all with his New York Dirty Room in 2005. Back in the day, a roomful of dirt asked why is that art? And the answer had to do with both shock and purity, as imperatives. Now everybody gets to play.

The whole idea of art as child's play is getting stale—to the point that you probably cringed when you heard that the Whitney will close its old home with Jeff Koons, before moving to the Meatpacking District at the foot of the High Line. Favaretto herself struggles to make enough of it to fill a wing at PS1. Like Koons, she has an unnerving eagerness to please. Fans blow still more confetti behind glass, into a party-colored clearing and mountains. New Year's Eve party favors unfurl with a click, thanks to black tanks of compressed nitrogen. Welcome at random to the party.

Like Koons or Damien Hirst, too, she can get awfully self-congratulatory and self-involved. Wild applause accompanies the green cube, as sound art called I Believe Nothing. Concrete blocks show her imprint digging, pushing, or leaning, while a slot in silver commands Your Money Here. Other walls retain a week's worth of dents and marks from a motorcycle's circling the room, ridden by guess who. She describes an informal library of found books, each with a found image slipped into its page and each free for the taking, as "research," an "archive," and a "blog." The black soil riffs on her own earlier work, converting a garden in Venice into a swamp.

For all that, she wants to take architecture seriously, like a proper Minimalist. Colored yarn in a corner, from ceiling to floor, makes a wall seem like a false wall, hiding something. She also means the metaphor of hiding or entombment as more than deriding the past, even if it means having her cake and eating it too. The black soil within its discrete metal box reminds her of a cemetery for a forgotten working-class hero, and she has buried something that she refuses to describe. Five tall spinning brushes of different widths and colors resemble a group portrait or a performance. They also resemble verticals by John Chamberlain, and I can always pretend that his crushed automobiles passed through her car wash—but I only wish that something of his achievement emerged intact.

"Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha" ran at Barbara Gladstone through August 3, 2012, Lara Favaretto at MoMA PS1 through September 10. Related reviews look at Lee Ufan and postwar Japanese art. Iván Navarro's well appeared in "Sculpted Matter" at Paul Kasmin, through August 17.