7.5.24 — Family and Friends

After my report last time on Della Wells, allow me a catch-up post for a review earlier this year of another African American, one that somehow I never published. A portrait by Marcus Leslie Singleton has the widest, whitest eyes that you may have ever seen. Dee Dee would be charming enough from that alone and her broad red smile, even were she not leaning so disarmingly toward a table set with flowers.

Their white and the deep blue of their stems and flowerpot erupt into a medley of white and blue in the sky, the leaves hanging down by her head, the seeming floral crown of her hair, her patterned dress, and the glints of color along her nose. But who is she? From the title, you might not know that Dee Dee is the black artist’s mother, which seems only right, for she deserves a life of her own. She opens a show in which every portrait is a study in relationships, at Mitchell-Innes & Nash through January 27.

Dee Dee speaks loudly of the eternal awkwardness and pleasures of family and friends. She has held onto an image of herself in a photograph—and he takes pride in painting it as testimony to his affection. Still, its reserved title attests to the distance that remains. Photos always do, even selfies, and the closest figure in a group portrait picks up his own camera to shoot right back. A family portrait makes room for nearly twenty figures standing or seated around a table set for a celebration, but not with the varying degrees of closeness that, in a royal family by Diego Velázquez, tempt one to ask just who loves whom. And will the lonesome turkey really feed them all?

Some look downright sullen, and Singleton leaves it open whether that arises only from his chosen limits as an artist. He adopts nearly flat fields of color for dark skin, bright interiors, and sunlit streets, akin to folk art. That and a focus on portraiture have become something of a norm for African American artists like Demetrius Oliver, Titus Kaphar, Amy Sherald, Mickalene Thomas, and Kehinde Wiley. The show all but picks up where Henry Taylor last year at the Whitney left off. If Singleton differs, it is in caring more about relationships and less about putting family, friends, and strangers on pedestals. Dee Dee has the only solo act in the show.

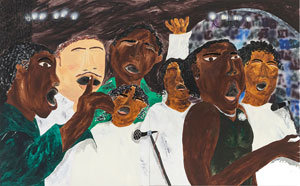

The rest are group portraits, unless you count a still life with no one at all in sight—but even there a close-up of a parent and child hangs on the back wall. Singleton works when he can from photographs, and who does not have a photo of nearest and dearest somewhere on display at home? Most are of special occasions, the kind that bring people together, like a Sunday choir in an excerpt from a photo that brings the faces that much closer to him. Still, what counts as special is up to them. Other kids are just getting together, basketballs in hand. But then the one on a bike could be riding past.

They combine the pleasures and displeasures of the special and the everyday. Singleton shows his affection while preserving a sense of humor and other marks of detachment. Shea Butter Babies has just one true baby, perched on the handlebars of a bicycle like a hood ornament, with protective shielding on her front that reads Fun Time. Then again, the two grown women behind her might be babes of a sort as well. Interiors and houses open onto half-seen rooms with decorations of their own. And whatever are the cars and kids doing parked along the shoulder of a road?

Yet the everyday may lead to transcendence as well, like Dee Dee’s riot of flowers. Man’s Soul Turning into a Rock promises an epic transformation. Is turning into a rock altogether a bad fate? The soul is himself turning blue, in the company of angels and a man kneeling as if in prayer. Rays from his eye and another man pierce the soul as if bringing it to life. Then, too, the boys by the side of a road are Blue Angels.

The leap from the everyday extends to Singleton’s technique as well. It blends oil and oil stick with spray paint, glitter, and glue. Free browns running up and down a wall have little in common after all with outsider art, whatever that means. It speaks of inclusiveness at that. People of color, it turns out, run to all sorts of colors, from near black to near white. One can still doubt whether the world needs yet another glittery young black portraitist and an escape from politics, but he is already sharing the awkwardness and the love.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.