Advise and Consent

John Haberin New York City

Art Advising 2.0: A Panel

"Art Advising 2.0: Vertigo and Accountability." It sounds so computer savvy, for a profession based on human relationships and precious objects. It also sounds dizzyingly close to chaos.

In reality, a panel on the proper role of art advisors, at Sotheby's Institute of Art, was comfortingly old-fashioned. It looked skeptically at the profession, but not at what many a high-end dealer would recognize as business as usual. Perhaps what has really changed is the dizzying growth of the art world—and the underlying puzzle may be the ethics of that.

An increasing role

Art advisors are growing rapidly in numbers and influence, and so are the difficult ethical problems that they present. The profession is self-regulating, with no certification required. It has attracted the former chair of Christie's postwar and contemporary department and the former chief auctioneer at Sotheby's, and it accounts for many millions of dollars in sales and as many as half of new requests for VIP passes to elite art fairs. It promises to bring together engaged buyers and sellers, yet it can also stand between them—and just four days later The New York Times reported on fraudulent transactions, with paintings by Amedeo Modigliani and others, in which an art advisor skimmed off tens of millions. If that sounds like a subject that can change before your eyes, according to your own role and perspective, the panel included four distinct points of view. And even that may not be enough.

The panelists represent practically everyone—except, perhaps, the artist, the collector, the midlevel dealer, and that nasty, perhaps unscrupulous character at the evening's core. Judith B. Prowda, senior lecturer at Sotheby's and the moderator, introduced them. They included a noted New York dealer, a lawyer conscious of the art advisor's obligations under the law, a fair director, and a representative of a leading association of art advisors. They also sounded anything but version 2.0. The dealer joked that he leaves surfing the Web to staff "under twenty-six." All presented themselves as holding those violating ethical standards to account.

The very idea of an art advisor may sound novel or downright peculiar. Collectors should learn to know and love art for themselves, no? Dealers should come to know them and respect them as well. Yet, as Prowda observed, art advisors go back centuries. They helped build great private collections now public museums, such as the Norton Simon and the Frick. One of the greatest of art historians, I might add, Bernard Berenson, made much of his living from it.

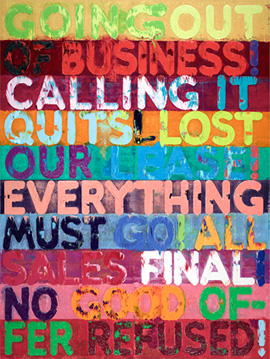

Yet the profession is burgeoning, because so is the art business. Sales reached well over than $50 billion in 2014, an increase of 7 percent. New York alone has somewhere between 500 and 800 galleries, depending on what counts as a gallery. Besides, by the time you have finished counting, the number will have changed. There are roughly one hundred eighty fairs, not even counting local ones, and they run all but nonstop. No one person can navigate a scene like this, not even a devoted critic.

As art advisors play an increasing role, Prowda explained, they also present serious risks to clients. Will they be working by the hour, on salary, on a retainer, or for a percentage of sales? If the latter, does that create incentives for them not to obtain a fair price? They may also hold potential conflicts of interest. What if they are "double-dipping," their fee split between client and dealer? What if two clients would have an interest in the same work?

Prowda outlined themes for the entire panel. Panelists, in turn, presented themselves as bulwarks against those very problems. For all their range of perspectives, that uniform pretense to virtue was itself troubling. Unlike a panel at Sotheby's last year on the art fairs, they did not sense a threat that artists, collectors, and dealers alike are not fully able to handle. In questions from the floor, Anthony Haden-Guest, the arts writer, made a point of the profession's "lousy reputation," and the panel was plainly uncomfortable in replying. The speakers merely reminded him that it was not a question.

The dealer as common sense

Sean Kelly, the noted New York dealer, presented himself as the congenial voice of common sense. As the embodiment of a hard-edged business person, he also revealed as little as possible. He repeated Prowda's statistics, and his brief presentation said nothing whatsoever about his experience. He began by stating that he knew nothing about the topic, other than sharing an Irish last name with another panelist, a good reason for drinks later. He became increasingly opinionated, though, over the course of the evening. He made it clear that he is encountering art advisors and, at times, turning them away.

The market truly is growing, he continued, at the very time that the movies and music face declining business, but with good reason. While other arts are now digital businesses, art is still an analog one. It is also still based on handshakes and trust, rather than regulation. Advisors play a useful role, amid the information overload. They can offer a GPS for buyers and sellers—or a bridge between them. Still, Kelly shied away from his own dealings, so I asked about just that.

To what extent have advisors entered his practice, and how? Do they introduce him to clients or keep them apart? Does he build relationships with them any differently than with clients? He did not answer directly, but more and more came out. We know the major players, he later said, and they are valuable. Yet if any tell him not to talk about prices in front of the client, for example, he refuses to deal with them.

Of course, any answer deserves closer examination—and so should the reasons behind art's robust business. For one thing, art includes digital media. Online art sales are increasing, too. Art has changed in other ways as well. It now reaches beyond an elite, but it is still a luxury good. That combination has special potency in a world of big money and mass entertainment.

Edward Winkleman, the savvy dealer and critic of art and money now without a gallery, pushed Kelly further. Suppose, he asked, a client and newbie advisor come to you, but the tyro is unable to represent the client's best interest? You risk losing one or the other, when you ideally want both. You do not want to break off a buyer's agreement, but you also do not want to kill off a future good advisor. Kelly dismissed the dilemma, replying that he would speak plainly to the client: "don't work with him."

Yet Kelly has a fiduciary obligation of his own that he might then be breaching, toward his list. As he himself put it, "we represent the artist." Even more, Winkleman was getting at the facts of life. In an overheated art world, the biggest problem may not be swindlers, but incompetence or, worse, what passes for the norm—and that applies to dealers and collectors as well. Kelly partly retreated, to state that he would simply be honest, as transparency requires: this guy is not doing his job.

A matter of trust

Fortunately, there already are legal protections. As Richard M. Lehun of New York Stropheus Art Law collective explained, they apply even in the absence of a written agreement that spells them out. In fact, if an agreement abrogates them, a court may rule that they still apply. Like a doctor or lawyer, art advisors hold a position of presumed expertise, with power over property belonging to another. Any such agent has fiduciary obligations. And of course the word fiduciary derives from trust.

First, fiduciaries must be loyal to the client, or principal. That means free of conflicts of interest. Art advisors cannot represent, for example, third-party interests. It also demands transparency, with no undisclosed profits. Second, they must be prudent, exercising due care on behalf of the client. Their fees, too, are "agency costs," subject to law.

I have little to add here, and indeed so did the panelists. The rest of the evening mostly affirmed their commitment to principles. They did acknowledge limits on one principle, though: third-party interests may still enter. What if one client has a work available, say, and the advisor believes that another client would desire it? Transparency, the speakers agreed, is key.

I have little to add here, and indeed so did the panelists. The rest of the evening mostly affirmed their commitment to principles. They did acknowledge limits on one principle, though: third-party interests may still enter. What if one client has a work available, say, and the advisor believes that another client would desire it? Transparency, the speakers agreed, is key.

Would it be enough? The question hung over the entire evening. For all the power of the law, no one seemed to think of things as safe and settled. And for all the agreement, almost everyone seemed eager for some firmer resolution. Conversely, no one wanted to admit to feeling at risk. Still, the last two speakers dived more directly into the fray.

Noah Horowitz, managing director of the Armory Show, adopted a more personal tone. He veered off-topic, as he spoke about people with lack of knowledge quite apart from art advisors. Still, he brought the abstractions closer to earth. Yes, he said, art advisors do create value in the information-based structure of the art world. If that results in more actively engaged clients, with greater fair attendance and more purchases, everyone benefits. At the same time, their presence can become overwhelming.

Actually, art advisors currently amount to only 15 percent of VIP passes to the 2015 Armory Show, third after collectors (50 percent) and other arts professionals. Still, they have replaced curatorial as art's most overused word. And, as Kelly said in response, a lot of them are not what they purport to be. (He makes a point of checking them out online—or rather having those twenty-somethings do so.) As Horowitz added, some even hawk their VIP passes on Twitter. And yes, transparency is crucial.

The enforcers

Who, though, will enforce that transparency, short of the courts? Are art advisors due for more uniformity or regulation? The Association of Professional Art Advisors (APAA) may be a step in that direction. It accepts members by invitation only. They do not own inventory, and they must read and sign a code of ethics each year, as a guide to best practices. Yet that still leaves questions.

Megan Fox Kelly, an APAA board member and herself an art advisor for eighteen years, spoke on behalf of an organization representing huge sales—less than 20 percent of this through galleries. And its guidelines correspond closely to what Lehun outlined: art advisors must act in the "client's best interest." They are to facilitate the relationship between buyer and seller, not obstruct. While payments may come about in any of the ways that Prowda described, they must come from the client only and must be disclosed. Again, too, advisors must disclose if they are selling work on behalf of one client that another client is seeking.

Due diligence entails an obligation to stick to one's expertise: "do not pretend to be what you are not." Art advisors should either conduct further research or bring in help when needed. The APAA recommends that agreements spell out those requirements. Doing so protects not just the client, but the advisor, too. Another questioner, an insurer, suggested that liability policies should state the fiduciary relationship as well.

Is Kelly saying that, if everything fell to the APAA, then everything would be fine? She might think so, for the association would only gain in authority and reach. Yet Sean Kelly and Horowitz were leaning that way as well. The theme came up more in passing than as a bullet point, but it was implicit throughout: an accrediting agency could be an enormous help. And here I am not so sure.

How would it work in a global marketplace? Could regulation protect foreign buyers who may never even set foot in American art fairs—or American buyers traveling abroad? Would it apply uniformly from state to state, and who would administer it? Who, for that matter, appointed the APAA? Would it actually raise costs? Think of how regulations that prohibit dental assistants from working alone without a dentist raise the costs of teeth whitening.

Besides, are advisors any more unscrupulous than art fairs and dealers? With calls for MoMA's chief curator to step down, how about museums? As Sean Kelly says, his is a handshake business—and many a struggling artist or dealer fears the power of an elite dealer's handshake. To end where I began, the growing power of art advisors is only a part of the growth of the art world. No wonder it all comes down to transparency and responsibility. The more all parties are aware of their risks and obligations, the more they can look after themselves and each other.

"Art Advising 2.0: Vertigo and Accountability" took place on April 1, 2015, moderated by Judith B. Prowda of Sotheby's Institute of Art. Related reviews take up Sotheby's 2014 panel on the art fairs, Christie's Education's 2016 panel on the future of the gallery, and Sotheby's 2018 panel on outsider art.