Letting Go

John Haberin New York City

The Future of the Gallery

This model just isn't working. I had never expected to hear those words from one of New York's finest dealers. I would hear something like them often again.

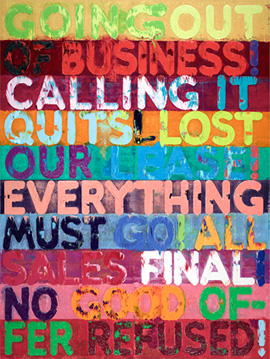

She had worked at the leading auction houses. She had started her own gallery and pursued it through three neighborhoods, from an elegant West Village brownstone to an airy split-level space on the Lower East Side—and now it, too, was closing. I hurried to its final show to say how sorry I was to see it go. But no, she assured me, she was not giving up on art. She was just taking stock and looking for alternatives to a "brick and mortar" gallery. There has to be a better model.

A panel at Christie's Education insisted on just that. "Letting Go of Brick and Mortar: The Future of the Gallery" was all about letting go. Three of its panelists already have. They have all had influential galleries or alternative spaces—and they have all given these up for a "hybrid model," of exhibiting from time to time while working behind the scenes with artists, estates, and collectors. Is that model, though, also available to emerging dealers, and what does it bode for art? As a postscript, a year later the questions have gained attention from the press.

The dealer as hybrid

Nicole Klagsbrun, Jay Gorney, and Josh Baer all came of age in the 1980s, what Gorney called a "magic time." Collectively, they have had success in the East Village art scene, Soho, and Chelsea. All have had galleries of their own. Gorney also worked with what later became BravinLee Programs and with Mitchell-Innes & Nash, while Baer made his name with White Columns. The fourth speaker, Richard M. Lehun of New York Stropheus Art Law, has spoken on the challenges to midlevel galleries from art fairs, art advisors, and outsider art. Together, they all but embody the transition from Modernism and its avant-garde to the chaos and disappointments of today.

The panel came with a further rubric, "Challenges and Opportunities"—but with the emphasis on opportunities. For Klagsbrun, it is the opportunity to use her office as "a place to grow at a pace that I dictate." For Gorney, it is the opportunity to sustain his long commitment to at least one artist, Sarah Charlesworth, and her estate. For all three, it is the chance to exhibit with established galleries, art fairs, virtual art fairs, or pop-ups, but without the obligation, as Klagsbrun put it, to feed the machine. Rather than the process of taking artists from studios to sales, she lamented, the art scene has become all about the product. By 2013 it was time to think instead about what is best for artists or, in Baer's words, "what is best for me."

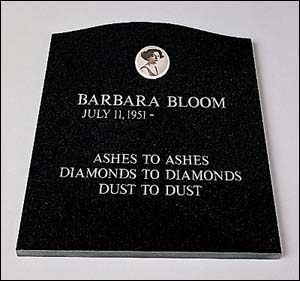

Plenty of others will know the feeling. I began by quoting Tracy Williams, who introduced me over the years to such artists as Barbara Bloom (whom Gorney can take credit for exhibiting in 1989). I hate to mention her by name, so as not to intrude on her privacy, but she is hardly alone. A slide at the panel listed galleries that have vanished this past year alone, and the shock came not just with their number, but also with their familiarity. Could a hybrid model offer them a better future? Is the crisis even real, much less the opportunities?

At first glance, the answer is no. Anyone who has just made it through the mass of openings that first week after Labor Day will want to call a time out. They will have other things in mind than the death of galleries. Despite clear signs of a retrenchment, they will have seen the obvious—more galleries, more crowds, and more money. The Lower East Side seems no longer an alternative, but a monster sprawling in every direction. And if it dies, surely Brooklyn is dying to snap up the remains.

At first glance, too, it seems preposterous to single out a crisis in art. New York memories extend to closed bookstores, hardware stores, and more. Even visitors to Chelsea galleries can no longer end the day at the Empire Diner, a favorite French restaurant, or a wine tasting at the neighborhood liquor store. Then again, those closings only underscore the pressures on galleries, and they are real. Even the spiraling growth brings spiraling pressures, in competition and rents. As Baer put it, "Of those six hundred galleries out there, how many will be flourishing twenty-five years from now?"

Galleries always come and go, because this is capitalism, and where there are winners, like the multistory galleries in Chelsea, there must also be losers. Even prominent galleries can succumb to a dealer's personal foibles or death. Now, though, everyone is on the line, including the seeming winners. I have reviewed Lisa Cooley more than any other downtown gallery, and now it is gone along with Laurel Gitlen across the street. An entire block of galleries has left Chelsea, and not all of them have turned up elsewhere. The author of How to Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery, Edward Winkleman, no longer has one.

Mr. Big

Once again one can object. They have made their choices, but so what? Others, as the director of Central Booking insisted to me, will keep going because that is what they do. She has to exhibit, because she in the game not for money and independence, but as a curator and in support of others. Do the art fairs just add to the pressures, with enormous costs of their own? No one is obliging attendance.

No doubt, but not everyone has a choice of people over profits, short of trust-fund babies. Still another dealer lost first her gallery and then a prime pop-up space—and this time I really shall omit a name, because she stayed in bed and cried for two days. We sat down soon after to discuss exactly the topic at hand: does she even need a gallery? A proper answer takes looking beyond successful hybrids or other mutant life forms. Not everyone has the same opportunities, but is a hybrid the solution all the same?

The panelists left the scene with formidable lists, formidable connections, and formidable reputations. They had neither stormed off in anger nor slunk off in despair, although a recession had left one of them little choice. They could afford to use the panel to cite their achievements in exhibitions and partnerships. They could afford, too, to imagine a scene with many fewer galleries—just enough, Baer said, "to change everyone's view of the world." They could afford to give up the hope, he added, that "Mr. Big is going to walk in the door and save your ass." What, though, if they each have Mr. Bigs to spare?

Working behind the scenes, too, has its costs. Art requires storage, shipping, and insurance. As Lehun explained, a private dealer also still has legal obligations. A dealer in new work or an art advisor has a "fiduciary responsibility" to clients, whether artists or collectors—which entails loyalty, prudence, and no undisclosed profits. A dealer on the secondary market is still subject to the Uniform Commercial Code and to tort laws, which protect against fraud and negligence. Either hybrid, he concluded, had better get good contracts.

Working behind the scenes, too, has its costs. Art requires storage, shipping, and insurance. As Lehun explained, a private dealer also still has legal obligations. A dealer in new work or an art advisor has a "fiduciary responsibility" to clients, whether artists or collectors—which entails loyalty, prudence, and no undisclosed profits. A dealer on the secondary market is still subject to the Uniform Commercial Code and to tort laws, which protect against fraud and negligence. Either hybrid, he concluded, had better get good contracts.

Other costs are harder to quantify but no less real. Artists want exhibitions and reviews, because they want people to see their work, and collectors want to see exhibitions and reviews, as a sign that the artist matters. Without them, private dealers may find themselves losing their buyers and their lists. The panelists have the clout to sustain both, even without a gallery, but how many others can say the same? Big-name galleries rely on them as curators as well, but only because their names add real value. Then, too, such partnerships affirm the importance of brick and mortar after all.

The problem of art and money boils down not just to costs and benefits, but to who pays and who benefits. Yes, artist collectives will survive, because their members support one another—even though they may never break through. Yes, the most elite galleries with the most established artists will survive, because people pay attention. And yes, a hybrid can survive, too, although it may find itself representing wealthy collectors as often as artists, with the potential for conflicts of interest along the way. Yet that still leaves plenty of others, including the midlevel galleries that do most to nurture a future for art. If young artists and dealers can no longer hit the city with every hope of changing awareness, that leaves not a more democratic art world, but one more closed than ever before and more open to cynicism about art.

A postscript: victims of success

Only a year later, The New York Times makes it official: galleries are closing. At the very least, they are under pressure from wary collectors, rising rents, perpetual art fairs, and ever increasing competition. That should come as no surprise. Galleries are a business, a bigger and bigger business, and anyone can see the turnover. The ominous opening of that 2016 panel discussion listed just some that have called it a day.

No, the surprise is not that galleries die, and others hurry to fill their spaces—in real estate, if not always in one's heart. The surprise is who. That panel included three of the most successful dealers over decades now, and now Andrea Rosen has shut its doors as well. Even The Times has to take notice. And the toll extends to more recent successes on the once gritty Lower East Side. As the Times headline put it, "Art Gallery Closures Grow for Small and Midsize Dealers."

Are there lessons? I think I got this right the first time, but consider the points again. First, the closings really do come less from artist collectives and others on the margins, who serve a smaller community, or from the very largest dealers with money to burn. That leaves midlevel dealers with every sign of growth and every fear of a market shake-up.  I never cared for the splashy displays at Mike Weiss, but they had started to get reviews, even as the gallery aggressively expanded its roster. Cooley, Gitlen, and now On Stellar Rays had all moved into bigger and more prominent spaces—in the case of On Stellar Rays, a space that a still more upscale dealer, Sue Post, had abandoned as well.

I never cared for the splashy displays at Mike Weiss, but they had started to get reviews, even as the gallery aggressively expanded its roster. Cooley, Gitlen, and now On Stellar Rays had all moved into bigger and more prominent spaces—in the case of On Stellar Rays, a space that a still more upscale dealer, Sue Post, had abandoned as well.

Second, they may grow sick of the struggle, but often as not they are not going away. Of course, the panelists touted a "hybrid model" of working behind the scenes, art fairs, and exhibitions in conjunction with surviving institutions. One of the three had cut back to handling an estate, and Rosen will do the same on behalf of Félix González-Torres, who died in 1996. The Times cites one dealer who will work with Paula Cooper, no spring chicken either. Lori Bookstein and Molly Krom are working the fairs. Others, like Hionas or Rooster, are taking stock, casing out other neighborhoods, and just plain wondering what comes next.

Third, the first two points are connected. Success breeds alternatives. That panel could afford to look ahead because it had the connections to do so—including clients, artists, estates, museums, and (yes) "brick and mortar galleries." Others soldier along because they have no choice. Without exhibitions and reviews, artists and collectors alike may quickly defect. I have already mentioned a dealer who cried for days after losing first a lease and then a prominent pop-up.

Last, the closings come at a cost—and not just to the dealers. Their former artists may now have a healthy CV and a deserved reputation, but others to come will go unnoticed. Rosen's last exhibition introduced me to video, performance, and sculpture by Martha Friedman, but it will introduce me to living artists no more. Older dealers cannot serve the living forever anyway, not if they want to stay loyal to their artists, as they should. And that is why smaller midlevel dealers have an irreplaceable role, even in a ridiculously bloated art scene. Have they survived Hurricane Sandy and "virtual exhibitions" after Covid-19 only to become the victims of their success?

"Letting Go of Brick and Mortar: The Future of the Gallery" took place on September 21, 2016, introduced by Véronique Chagnon-Burke of Christie's Education. The article on closings in The New York Times appeared June 25, 2017. A related review looks at claims for the death of art fairs after Covid-19.