Will MoMA Ever Change?

John Haberin New York City

Klaus Biesenbach and Scenes for a New Heritage

Do I really have to weigh in on whether Klaus Biesenbach should step down? Not if you seriously need to ask whether the Museum of Modern Art, where Biesenbach is chief curator at large, is sadly off-course. Not, too, if you are seriously expecting MoMA to budge.

Yet the 2015 outcry is real, and so is the shameful state of affairs behind it. The debate began in March, triggered by critical reaction to a show of Björk, the Icelandic pop star. And the issues go well beyond any one exhibition.

As a postscript and a sorry example, the museum weighs in on its future with "Scenes for a New Heritage." Yes, I know, with all that space devoted to a pop star, it has grown awfully lightweight. It has brought lines to watch music videos rivaling Disneyland. It has drawn those cries for its chief curator to step down (which would be great if he could take the board and senior staff with him). But rest assured: when it comes to contemporary art, MoMA is deadly serious—and I mean deadly.

Sharing the blame

Christian Viveros-Fauné set things off in ArtNet. Also a critic for The Village Voice, he had a gallery in the glory days of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, introducing me to such artists as David Ersser, Christoph Morlinghaus, Beth Campbell, Christoph Draeger, and Eve Sussman. He also co-founded Volta, the art fair whose insistence on single-artist booths has by now influenced even the ADAA Art Show. If anyone has his finger on the pulse, it is he—and indeed he began his article by noting disillusionment at MoMA itself. At an event to celebrate Björk, many of the museum's own trustees stayed away. Before long Jerry Saltz took a selfie burning his press pass, although I have a feeling that he could gain admission by waving his Mickey Mouse Club membership card.

The trustees, Viveros-Fauné observes, feel betrayed as much by Biesenbach's "unprecedented autonomy" as by the exhibition. The curator has acquired the freedom to do pretty much what he likes, and he prefers the company of celebrities to museum professionals—including celebrities like Björk. Defenders do not exactly inspire confidence either. Jeffrey Deitch offers his support, but then the former Soho dealer has his own record of glitz, chumming around (with, for one, Klaus Biesenbach), mismanaging a museum (LA MOCA, of course), and alienating its board, which soon enough got rid of him. Others argue that if Björk is so bad, where was the anger when MoMA exhibited Tim Burton back in 2009? But then that may say more about a slow critical response than about Björk.

Still others shift the blame to the director, Glenn D. Lowry, or to the board, as if they were any easier to remove. One might not like it either if the board did bear responsibility, for that would mean a museum run by and for its largest contributors. Maybe a little curatorial autonomy is not so bad after all. Still, that objection has a real point. A museum's past, present, and future do not rest in the hands of any one person, and one cannot address its problems by wishing someone away. Look carefully at the Modern's track record, and you may find yourself questioning its board, its director, its senior staff, and even its role in art today.

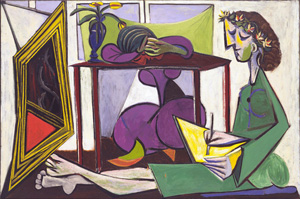

Sure, start with Björk and Burton, although in all fairness the latter offered more than a retread of music videos, memorabilia, and souvenirs. The New York Times slammed a "puffy" exhibition of late Picasso, but contemporary art has fared little better. Many saw Marina Abramovic in performance as a circus. And Biesenbach is also director of MoMA PS1, all but effacing its origins as alternative space in favor of a pebbled courtyard good for little more than summer parties. No wonder Roberta Smith in The Times has asked whether MoMA is dead. She hoped not.

All these reflect an almost single-minded dedication to circuses, at the expense of the permanent collection. MoMA's 2004 expansion, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi, devotes way too much of its space to just that. It certainly has not answered critics of a lack of attention to women. Expansion also handed over much of the joint to its atrium—like, I have lamented, a hotel with a poor excuse for a piano bar. It has made the institution as much a real-estate empire as a museum, planned around a condominium tower. And now it has destroyed the landmark architecture of its former neighbor, the Museum of American Folk Art, on the way to still more of the same.

All this entails a drastic reorientation of the Modern's relationship to its audience. It was the first to jack up museum admission, although the Guggenheim now matches its price—and it has broken with the very heart of PS1, in that "pay what you will" does not get one into an additional installation for (yes) Björk. Its design store has targeted the market for luxury tchotchkes, and its crowds threaten to turn it into a tourist hub from which artists and New Yorkers turn away. And that is exactly why its course is so hard to change. The board truly has directed its worst mistakes, and it has to be pleased with the results in sheer numbers. If trustees feel excluded by Biesenbach and Björk, they may just be hungry for more.

Sharing the hope

MoMA is not alone. Museums everywhere are stumbling into a glitzy but uncertain future, like the Jewish Museum with a display of Leonard Cohen, and one big reason is money. Art in a time of art fairs, art advisors, biennials, triennials, and blockbusters has become both far more popular than ever before and more of a luxury good. The two may well go hand in hand.  Even Viveros-Fauné has come under fire for conflict of interest, as critic and director of an art fair. (For the record, I have cleared him of the charges, and so apparently has the art world.)

Even Viveros-Fauné has come under fire for conflict of interest, as critic and director of an art fair. (For the record, I have cleared him of the charges, and so apparently has the art world.)

The Modern has its unique dilemma as well. How can it define its mission, now that Modernism is no longer contemporary? Is it turning Modernism into history or enabling the future? To be sure, others face similar questions. The Whitney has to redefine a museum of American art in an increasingly global culture, even if that culture also values diversity. And it, too, no longer has a lock on emerging artists in "Greater New York 2015" and "Greater New York 2021."

No other institution, though, faces the dilemma as much this one. An exhibition boasted of MoMA in Y2K, on its sixtieth anniversary, without quite explaining why (and the Met will have its celebration with "Making the Met" in 2020). Recent displays of political art and abstract painting look tailor-made for global markets. The museum can still pull off wonderful exhibitions, such as Matisse cutouts, Jacob Lawrence, and postwar Latin American architecture. Who else could bring that kind of scholarship to the twentieth century? Yet these exhibitions also look safely to the past.

At the same time, they hold out hope. The Modern still has the staff and the resources to do more, much more, and changes at the top could unleash them—just as at the Whitney under Adam Weinberg or the Met under Thomas P. Campbell. Change there has come quietly since the departure of Philippe de Montebello, but it is everywhere. Curators are more willing to take risks, as with Renaissance tapestry and Native American art. The Met has also rededicated galleries to its collections of European painting and American art, including Native American "Water Memories" and a splendid recovery of murals by Thomas Hart Benton, coming off the fine work under de Montebello on its Islamic wing. I cannot imagine ego trips like the Lehman wing or wasted space like its vast, two-story corridor for sculpture again.

One can complain about any museum. Plenty of shows are duds, and plenty of museum expansions, as at the Morgan Library and quite possibly the Whitney, are headed much the same way. Curators at the Met still have a tendency toward self-congratulation and an utter certainty in disputed attributions. They have not yet featured a pop star, but they keep drawing long lines for high fashion. Still, that is fully in accord with the Met's mission, which includes the history of design. And it remains pay what you will.

Will MoMA ever change? I have my doubts. By every measure, it already counts itself a success and I myself cannot say how it should change, for the dilemmas of money and mission remain. Yet that also means that it has already changed since its birth, and it could change again. A great collection is still ripe for a new beginning and a rediscovery of its past, but Lowry and Biesenbach really would have to go, and the board really would have to change its attitude. It is up to them.

Deadly serious

The good news is that museum holdings have returned to the galleries for contemporary art. In an institution that shows so little interest in its collection, that means a lot. Say what you will about the retrospective of Robert Gober, it was just that—a retrospective. The latest selection, running a full year, announces a commitment to collecting right in its title, "Scenes for a New Heritage." The bad news is a stifling uniformity. Nearly everything is big, loud, and desperate to make a statement.

Where "The Forever Now" upstairs deadens abstraction, to the point of "zombie formalism," the second floor does the same for political art. Mladen Stilinovic even calls echoes of early Modernism Exploitation of the Dead. What looks like an abstraction, by Yto Barrada, actually amounts to corporate logos, for a "post-colonial history . . . from a non-Western perspective." Allan Sekula's photos of coastal fishing really document the "global economy," and a brooding port city for Seher Shah reflects on Pakistan as akin to a "black star." Prints by Mark Bradford and Thomas Hirschhorn have something to do with politics as well, although I have already forgotten what. Shahzia Sikander and Kerstin Brätsch indulge in pattern and decoration, Takashi Murakami in manga, but they are the exception, not to mention blah.

Political art here is at once hectoring and vague. "Zero Tolerance," a compendium of protest at MoMA PS1, may reduce politics to nostalgia. The New Museum Triennial, buried in new media and wall text, may have you scratching your head to penetrate its "Soft Water, Hard Stone." You are more likely to leave this show with a shrug. Some of the art cultivates its artlessness, like photographs of South Africa by David Goldblatt or Hito Steyerl's video tribute to a martyr to Kurdish independence.  Some goes right for the lecture, like Columbia University's Architecture and Justice project, with a visual and textual mapping of incarcerations, or Rirkrit Tiravanija, who assures would-be grammarians that The Days of This Society Is Numbered. By far the most manage both, like Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in a hotel sign, Rabih Mroué in cell phones from the Arab Spring, Cady Noland in a trip across America, Camille Henrot in a purported history of the universe, or Félix Gonzáles-Torres in a light show.

Some goes right for the lecture, like Columbia University's Architecture and Justice project, with a visual and textual mapping of incarcerations, or Rirkrit Tiravanija, who assures would-be grammarians that The Days of This Society Is Numbered. By far the most manage both, like Hüseyin Bahri Alptekin in a hotel sign, Rabih Mroué in cell phones from the Arab Spring, Cady Noland in a trip across America, Camille Henrot in a purported history of the universe, or Félix Gonzáles-Torres in a light show.

Not that its artists are all to blame, not when they include On Kawara and Kara Walker. She gets a full wall for her silhouettes of plantation stereotypes. They are international as well, with New Yorkers the rare exception in search of a rule—although a global art scene imposes its own uniformity. Many also appear rarely at MoMA, like Cai Guo-Qiang with his wooden ship pierced by arrows, or for the very first time. Of course, that, too, can backfire. It can remind you of the museum's limited attention to its art.

I found moments of beauty, like a stormy history of Soviet bloc architecture from David Maljkovic, objects out of everyday life and surgery from Doris Salcedo, ants collecting colored paper from Rivane Neuenschwander with Cao Guimarães, and a ghostly photo of an enormous tree from Tacita Dean. I found poignancy in the political, like the roster of Uruguay's "disappeared," which Luis Camnitzer inscribes in the phone book. I found more than enough silliness, like China's Long March as video game by Feng Mengbo. I lost every last shred of patience with Sharon Hayes, as she declares her anxiety and her love "in this dry desert of existence." I felt mildly enlightened by Alfredo Jaar and his record of censorship. And then I walked into the blinding light of an empty room, where Jaar translates that erasure into experience, and it all faded away.

Christian Viveros-Fauné wrote on March 24, 2015. "Scenes for a New Heritage" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through April 10, 2016. A related article rehearses many of the same issues as far back as 2011. As of fall 2018, Klaus Biesenbach is heading off for LA MOCA.