The Art of Abundance

John Haberin New York City

Barbara Wolff and Jewish Tradition

Repetition and Difference

"How manifold are Thy works, O Lord! In wisdom hath Thou made them all; the earth is full of Thy creatures." What happens when a skilled technical illustrator turns to the Bible? Is the result science, fancy, or revelation—or can it encompass them all? For Barbara Wolff at the Morgan Library, it is first and foremost abundance.

The Jewish Museum raises still more expectations—repeated and different. "Repetition and Difference" gathers over three hundred fifty objects from its collection (talk about repetition), some older than the Bible. They range from Iran to Israel and from Eastern Europe to the United States.  It brings them together with contemporary voices from four continents, including one of the most prominent African American artists going. If any are Jewish, the museum is not saying. It also takes its inspiration from a prophet not of ancient Israel, but of post-structuralism.

It brings them together with contemporary voices from four continents, including one of the most prominent African American artists going. If any are Jewish, the museum is not saying. It also takes its inspiration from a prophet not of ancient Israel, but of post-structuralism.

The Bible unbound

Barbara Wolff takes those words from Psalm 104, and she sees that abundance everywhere—in the earth, the sea, the sky, and the imagination. Her illustrations proceed verse by verse, beginning with the signs of the zodiac, because of their place in Jewish art and Jewish antiquities at least as early as the Hellenistic era, their number sometimes linked to the twelve tribes of Israel. These are by no means perfunctory reminders of nature, from an artist who has also worked for the Time-Life Nature Library and the New York Botanical Garden. They are fully observed fish, shellfish, arthropods, and mammals. The Maiden carries a recognizable harvest, and the Water-Bearer is a jellyfish. Yet one cannot miss the fancy in the turn of a lion's head or sea-goat, the archer's bow pointed directly at the scorpion, or the jellyfish raising two tentacles in a dance of triumph.

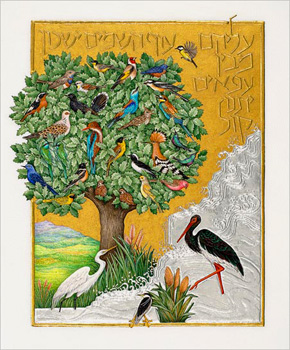

They are also in raised gold leaf, like the burst of energy at the illumination's center, and in motion, like the northern lights shimmering in a starry sky. Wolff has a fondness for natural worlds in collision. As "the waters stood above the mountains," she imagines forces deep within the earth enacting the separation of sea from dry land in Genesis. Other verses pack entire bestiaries into a tree or garden, each creature out to assert its place in the creation. She finds the same abundance, too, in the Haggadah, the prayers and passages from Exodus read aloud at the Passover Seder—not unreasonably, given a ritual of renewal in springtime. Her illustrations for the Joanna S. and Daniel Rose family Haggadah celebrate the evening meal with sheaves of wheat and a vessel overflowing with grapes and flowers.

The Psalm and Haggadah appear unbound, along with an iPad and Web site that allow one to visualize turning their bound pages. The Morgan sees them as another kind of collision as well, across cultures and centuries. Wolff has exhibited before with the Museum of Biblical Art and a number of Jewish institutions, without giving up her commitment to natural history. As "the mountains rose," jagged planes of gilded earth bear text in raised Hebrew letters, but also a reminder of what a geologist would call plate tectonics. She is also reviving and explaining the techniques of illuminated manuscript, on parchment and vellum, in collaboration with calligraphers whose block Hebrew and English italics are her art's equal. A case holds the knife with which she applies gold, silver, and platinum foil—and a film shows her at work with a variety of pens and brushes.

The Morgan has its own stake in these worlds in collision. Wolff found inspiration in the Hebrew Bible, in a 1917 translation for the Jewish Publication Society, but also in Christian book art at the Morgan—such as a Book of Hours, the Crusader Bible, J. P. Morgan's Bibles, the Medieval Housebook and "The Medieval Hunt," and the work of Jean Bourdichon. They encouraged a greater realism and paved the way for the Renaissance. With Wolff's "Hebrew Illumination for Our Time," the Morgan also insists on its place in the present. A concurrent exhibition of "Embracing Modernism," with more than a hundred drawings curated by Isabelle Dervaux, boasts of that as well.

It shows the fruits of a decision just ten years ago, to enter the market for Modernism and art today, and I confess to mixed feelings. For the exhibition itself, one can do little more than praise the museum's taste and energy, since little else unites the hit-or-miss work or illuminates its time. Everything is here, from Henri Matisse to Marlene Dumas—with clever pairings of frottage, or rubbings, by Max Ernst and decades later Robert Overby, fine art and "low" art cartoons by Caroll Dunham and Roz Chast, block-like enigmas by Balthus and Marisol, incisive family portraits by Erich Heckel in German Expressionism and Walter Sickert in England, or self-portraits by Egon Schiele and Maria Lassnig. Despite limited examples of major movements, it can boast both a Surrealist drawing by Jackson Pollock and a sketchbook from his drip period. Still, there is only so much money, and there is only one Morgan Library. Other institutions can attend quite well to the last century, and gains here have to come with a tradeoff in lost opportunities from the past.

A preceding show of Cy Twombly could almost change my mind. Twombly carried a single broad horizontal across five sheets of gray—hinting at musical notation, a horizon, the wall itself, the architecture of drawing, and a glimpse beyond. And then there is Wolff, whose hard-edged figures and rainbow colors attest to joy and abundance, if not quite to pain and scarcity. Even the Israelites toiling as slaves in Egypt and the pharaoh's soldiers drowning in the Red Sea appear reasonably upright and dignified. The artist titles her version of the psalm You Renew the Face of the Earth. The quote refers to a higher power, but it could describe a work of art.

Split the difference

Will "Repetition and Difference" be a survey of Jewish art and culture made relevant for today or a Postmodernism rooted in the past? Will the Jewish Museum describe the persistence of racism and anti-Semitism or seek common ground across race and religion, grounded in mutual respect? In a word, no, in a show that does not ask more of contemporary art, much of it abstract, than to go about its business—much like a show of "Unorthodox" soon to come. With nine artists and eight tight groups of objects (talk about difference), it does not even strictly pair the two. Nor does it ask the artists to respond for the occasion to artifacts on display. Rather, it weaves them into an installation that invites one to find one's own pairings.

One will, too. The show has a slippery and inviting notion of repetition or difference, perhaps its only debt other than its title to Gilles Deleuze. All just as well. Well-meaning museum commissions have a way of distracting artists from their work, as so often with the Guggenheim's Hugo Boss prize—or practically the entirety of the 2015 New Museum Triennial. As for the French philosopher, finding oneself in a recognition of others has a long history, from Hegel to existentialism, and his 1968 book reads like them both on drugs. The show is a welter of lost opportunities, but also some found ones.

One will, too. The show has a slippery and inviting notion of repetition or difference, perhaps its only debt other than its title to Gilles Deleuze. All just as well. Well-meaning museum commissions have a way of distracting artists from their work, as so often with the Guggenheim's Hugo Boss prize—or practically the entirety of the 2015 New Museum Triennial. As for the French philosopher, finding oneself in a recognition of others has a long history, from Hegel to existentialism, and his 1968 book reads like them both on drugs. The show is a welter of lost opportunities, but also some found ones.

The finds begin with the invitation to the collection for those not already interested in Jewish tradition. One can come to marriage contracts for their connections to Jewish but also Islamic art, in the naturalism of birds and lions—the last a symbol of the Persian empire. One can see playfulness and invention in the ritualism and conformity of brass Hanukkah lamps from Galicia and Ukraine, extending to represented candles within a setting for real ones. One can encounter differences even in coins, the very emblem of standardization, but stamped in ancient Tyre in silver by hand. One can see Torah binders and mezuzahs, both holders of Biblical verses, in context of the present as text art and the artist's book. A close assembly of skullcaps, from multicolored to patterned cream, might pass for a party.

So might Amelia Pica's confetti—or rather the remains of one after the people have departed, ever so easy to miss on the floor nearby. The curators, Jens Hoffman and Susan L. Braunstein, point often to presences and absences. Walead Beshty, whose past work has included Absent Self-Portraits and the direct traces of things in photograms, here has taken a large drill to five flat-screen TVs, leaving a glowing hole in each one and thin lines of color radiating vertically and horizontally. He also strikes through the work's title. Kris Martin does his own severe damage, but to polystyrene heads used to display wigs, before casting them in bronze. They sit just across the room from clay female figurines from Israel's southern kingdom, ambiguously divine or human, objects of worship or destruction.

These pairings are straightforward enough, but not all. Koo Jeong-A's wall of bar magnets may echo nearby metalwork or quite another source of attraction, the aromas that once filled spice containers—or maybe not. Three neon signs from Hank Willis Thomas blink on and off with slogans for VISA and Caesars hotels. Should one look from credit cards and casinos to coins from around the time of Jesus an entire room away, perhaps to render unto Caesar? Should one look closer, from "The Life You Were Meant to Live" to the Torah and Jewish law? Thomas multiplies even repetition. Think of quotation, a chain of hotels and plastic, slogans in advertising, the very nature of language, and an edition of three.

Other connections are more tenuous still, except perhaps as connections to one another. John Houck, who later turns to painting, folds paper before photographing it, folding the photograph, and photographing it again, while N. Dash nurtures folded paper like abstractions as containers for personal possessions. Abraham Cruzvillegas has his own folds, in an ellipse of cardboard and clippings painted gold—reminders, he says, of crude housing built of found objects in Mexico City. Five panels by Sarah Crowner, who has said how her geometry "bounces from one work to the next," repeat and differ mostly within themselves. Even the selection looks within, given that art has dealt in repetition from saints and Madonnas to silkscreens, Minimalism, and appropriation. For so large a collection of book art and objects, the show is arbitrary and modest, but with ample space for some very good artists.

Barbara Wolff ran at The Morgan Library through May 3, 2015, "Embracing Modernism" through May 24, and Cy Twombly through January 25. "Repetition and Difference" ran at the Jewish Museum through August 9. A related review looks at Wolff and the Book of Ruth.