From Wild West to Inner City

John Haberin New York City

Chelsea's Early Fall 2007

Only a couple of years ago, September came with a shock. Smaller communities might coordinate a monthly gallery night, but never Chelsea. How then could so many shows have opened at once, all on the very first Thursday evening? And how could so many people have turned out to see them?

Visible and invisible hands

Ordinary New Yorkers treat Labor Day as the end of summer, a reminder not of labor movements past but of all that labor to come. But surely not art, just as so many late spring shows run well past Memorial Day.

Of course, the invisible hand of the market is behind it all. Time is money now, just as earlier and earlier runs for president attempt to manage the political circus. Manhattan does not know from block parties. It knows from pressure.

The crowds bear an obvious relationship to the art within as well, much as at the later fall opening of the New Museum on the Bowery, amid a newly active Lower East Side. They favor shows loud enough to compete with the noise, massive enough to grab the crowd's attention before it drifts on, simple enough to make sense in a minute or two, and scattered enough to go with the flow—or the excrement. The invisible hand has produced some ham-fisted art.

Perhaps no exhibition had the apocalyptic furor of the year before. No artist had yet burst the gallery walls, and one could freely navigate even the most ungainly installation. Yet the market shows it can make and break not just careers but the work as well. Sadly, the only way to take the situation seriously as a critic is, this once, to rush through a dozen shows—and I mean as fast as I possibly can. And so I shall. (But no, I did not catch all these that night alone.)

This art thinks big, with ancestors not just in popular entertainment but in Pop Art and age-old myths. From Adam Helms and T. J. Wilcox to Jeff Shore and Jon Fisher, it may root its spectacle in the wide-open spaces of America.

Do not forget closed-in spaces as well. If Chelsea looks like a shoot-out in the Wild West, these shows also reflect the special pressures of New York. No wonder many artists turn to real and imagined cities. Larry Clark, Brad Moore, and Eva Struble reflect their streets, parking lots, and abandoned industry. Finally, Jules de Balincourt, Dean Monogenis, and Liset Castillo take the city as anxious object.

Fighting for a place

The crowds in Chelsea know better than to come back on a single evening next month. They knew before they arrived, though, what others were missing—and they were missing plenty of white walls, Rolling Rock, and white wine. By now, shock has given way to awe, far from the spirit of the first Chelsea art walks more than a decade ago.

As recently as 2004, I myself wrote about the slow pace of September openings, like art's Indian summer. A year later brought a study in mass entertainment, and in 2006 even that had given way to sociology and economics. One naturally attended a little less to the openings and a little more to the scene that knew to follow them. One noticed the people strolling or hurrying from place to place. One noticed another kind of growth, too, in big gallery buildings about to open.

This year, the economics dwarfs at once art and urban studies. I must have rushed through thirty galleries that night, limited only by the approach of 8 P.M.. Barely an hour before, I had been enjoying my ease in near empty rooms knowing all too well what lay ahead. Now I found myself not so much drifting from group to group as fighting for a place.

At one posh establishment, people waited or cut in line to enter, few could easily get near the art, and fewer still had time to care. I got a kick out of finding that, like the September before, another was handing out a micro brew, as later in the year it will not. I got a bigger satisfaction out of seeing another wealthy stalwart reaching out to anyone—and with particularly coarse wine at that. The press also drove home another new lesson in economics. Except for a few prestigious galleries like these, market forces have created a new order out of the early fall chaos.

Upscale galleries often open on a Friday or Saturday, perhaps by invitation only, to separate the business of nurturing customers from mere basking in publicity. Others will not open for another week or two to come, and one can no longer blame it on new construction. That Thursday, the north side of West 24th Street stood almost dark. The entire evening displayed in microcosm the tension right now between art as blockbuster and art as dozens of independent niches—between art as the struggle to stand out from others and art as the struggle just to go one's own way.

Some have seen the commercialization of art as a welcome openness to mass culture. Here little more than the media themselves—and perhaps the visitors—relate to what Jean Baudrillard termed the society of the spectacle. For this art, meaning develops, if at all, not from the specificity of associations or a collision of archetypes, but from sheer lack of constraints.

Outer and inner spaces

Two different galleries, only doors apart, play out Wild West themes. Adam Helms uses almost an entire gallery building for a decrepit plywood fort, huge pencil drawings of jagged hills that Albert Bierstadt would have envied, bleached period photographs given hoods and ski masks, a stuffed bison, and probably whatever else sprang to mind. T. J. Wilcox's photographs and video meander across four rooms just down the street for images of settlers, Indian raids, the princess of Bavaria, a fashion model, and Jackie Kennedy in the nude. Both artists look westward for scale and myth. To both as well, the myth describes the old cycle of desire, achievement, destruction, and failure.

Instead of a bull in a china shop, imagine a teenage boy let loose in the living room. Friedrich Kunath remembers a scene of struggle against adult realities, starting with death. A TV sits submerged in a bathtub, paint-spattered black stairs lead to a heavenly nowhere, and jeans clothe a coffin. Keith Tyson sets out his adolescent fantasies in Large Field Array. The artist refers to a colossal radio telescope in New Mexico, but he sees oedipal spankings rather than distant stars. The neat rows of tacky sculpture serve to emphasize by contrast how little he has edited out.

Think of the market as a dull roar or a sleight of hand? Dressed in the black tie and tails of a magician, her top hat shielding her face, Jamie Isenstein bows away at her handsaw violin. Ready instead to quote Baudrillard? Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba projects wall-size, overlaid images from cable TV and other fair and balanced sources. Jim Drain scavenges junk shops for used curtains and toilet humor. Yet the loud, tie-dyed colors place them all back in the summer of love.

Even abstraction borrows from classic comics. Emilio Perez's flat colors and black, jagged lines lack only bubbles screaming Pop! and Bang! In her transition from drawing to painting, Ingrid Calame, too, looks toward larger, brighter, and splashier shapes. She still includes several big works on Mylar that show how far a colored pencil and, she says, found markings can carry her—perhaps the best argument of 2007 for reading the press release. Like oils for David Reed, they also play at once with the transparency and shallow field of Abstract Expressionism and the materials of a real film. Her paintings, though, look almost solarized—and, I have to admit, rather lively as well.

One spectacle mixes its crudeness with ingenuity, humor, and maybe even meaning. It does not even require a big gallery. Jeff Shore and Jon Fisher stick up on the walls half a dozen contraptions that Tim Hawkinson might have borrowed. They have any number of cheap circuits and moving parts, not to mention a bunch of turntables. And, oh, did I mention a video, too? That projection soars across a black-and-white dream landscape and settles into a kitchen, where an on-screen reel-to-reel promises to reenact the scene.

For more than ten minutes, its vision cuts from the imagination to the surveillance camera to self-reference. However, these mental spaces have mechanical origins. The camera sees what no human eye ever will, and its self-reference extends beyond the projected tape player. It all starts when the gadgets kick in and small, mobile lenses peer into their interiors. Somehow, the cacophony of images and sounds becomes an intelligible soundtrack and an illusion.

Abandon spaceship earth

After all those signs of success and anxiety, it makes sense that many of the best shows examine the city itself. They do not so much depict New York City, much less Chelsea (or Wall Street). Calame found her traces in a real city—on the streets of LA. Larry Clark, too, tackles Los Angeles—and all within the last three years at that. More often, however, the artists describe an ideal city as a site of possibility and foreboding.

Like all his work, Clark's photographs of street teens have one foot in documentary tradition, another in glamour. Make that knee deep in pretence, and that can make his work hard to accept. Documentary photography supplies the unvarnished close-ups. Glamour photography isolates one or two sitters from their surroundings and lets them show off. Others have communicated more of the subject's blankness, anomie, violence, or cost, like Catherine Opie, and Clark himself has milked images of self-abuse to greater theatrical effect. But this is LA, after all.

Elsewhere, people rarely appear in this month's urban scenes. They may borrow their emptiness from landscape traditions and American myths, just as human beings intrude only at the edges in the Hudson River School. They may suggest the proverbial blankness of suburbia's burgeoning geometries or the same "Course of Empire" as in the rickety housing of Thomas Hirschhorn or the abandoned factories of Ed Ruscha. They may have the high-tech flavor of a science fiction dystopia. They still hold out some utopian promise. In other words, they look just like the art scene, only quieter.

One can sense the seductions of emptiness in photos by Brad Moore. His show's title speaks of the "Familiar," but no one is on hand to recognize it. The buildings appear as stage backdrops for their empty lawns and parking lots. The lack of development, the oddly uneven architectural styles, and the exaggerated gloss of the prints and their mounting may unfold in Orange County. If that distinguishes them from Clark's LA in wealth, style, or human possibilities, one would hardly know it. I liked them better, too, for that.

One can sense the seductions of emptiness in photos by Brad Moore. His show's title speaks of the "Familiar," but no one is on hand to recognize it. The buildings appear as stage backdrops for their empty lawns and parking lots. The lack of development, the oddly uneven architectural styles, and the exaggerated gloss of the prints and their mounting may unfold in Orange County. If that distinguishes them from Clark's LA in wealth, style, or human possibilities, one would hardly know it. I liked them better, too, for that.

Like the haunting prints of Benjamin Fink and Alex Prager, they make a metropolitan region less a scene of life than a staging ground, perhaps for space invaders. Eva Struble finds the same thing closer to home. Struble sets her paintings midway between artistic developments in Greenpoint and Long Island City. She makes use of the isolation and unfamiliarity of Newtown Creek, which divides Brooklyn from Queens, with nary a bar or club to be found. Her landscape includes factory sheds, fence posts, piers, and piled tires. As a former resident of Sunnyside, I could almost smell it.

Often her off-kilter compositions and blotchy paint areas approach abstraction. At the same time, the cartoon reds, pinks, and oranges show the influence of commercial illustration. Either way, she makes unsightly subject matter almost appealing. The tires cross a foamy white field that could easily pass for snow back in John Sloan's Greenwich Village of the 1920s. In New York now, a staging ground implies gentrification, and the city has promised a clean-up of the creek for as long as I remember. This show, too, looks both to the past and the future more than to the present, and it trades on a city's ambivalence about both.

Pain, hope, and whatever else

Clearly urban anxieties cannot all reduce to 9/11. Other fall openings raise those anxieties and fantasies to a fever pitch. One hardly knows where to point. Can it be folk art or science fiction, globalization or global warming, politics or art, gentrification or suburban sprawl? (An African America artist, Dewey Crumpler, raises much the same questions.)

Jules de Balincourt made his name with echoes of all these. Even his own bad jokes lettered along the edges cannot account for the mix. He runs through so many styles and themes that he seems desperate for one of his own. He also risks running in place.

A map is back, like the one of the United States upside-down that earned him fame. Still, China's unfamiliar patches bring him closer to abstraction than to satire. Clouds gather, but lofty cumulus clouds. Tropical trees enhance the lushness of a lake or pond, but no one is bathing. Laser lights rake across an unreal city, but no space invaders have landed.

Balincourt calls the show "Unknowing Man's Nature," as if he were unlearning his own hasty conclusions from just a year or two before. In short, everything attests to ambivalence, even ambivalence about whether to worry. It makes sense for an artist born in Paris looking at America. It makes even more sense since he gained so much status so quickly by playing on American culture and global alarm. But does it make sense for Americans not smitten with global trends? Sometimes.

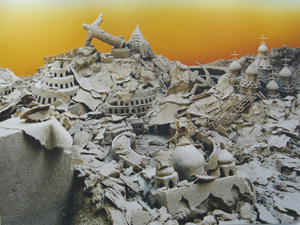

With her own course of empire, Liset Castillo comes closest to Thomas Cole—in her imagery, realism, and poignancy alike. As with Cole, a broad landscape unfolds in time, and a civilization rises and falls. Her exhibition title, too, recalls the Hudson River School painter's belief that sometimes nature has to run its course: "Pain Is Universal, but So Is Hope." She has something of his Romanticism, in wanting both to surrender to a higher power and to impose the painter's cosmic vision on history. However, her struggle with a corrupt civilization began in her native Cuba, and her struggle with nature for creative control starts before she even gets behind the camera.

Castillo makes explicit the idea of representation as a model of reality. She builds her city literally on sand, but not just with sand castles. She needs sand cranes to help erect them and a sand Madonna to protect them. Then she helps out entropy a bit in toppling them over. The warm photographs lend the molded objects the solidity and grain of concrete. They gain that texture particularly in smaller, sparer photographs of highway intersections.

Fantastic planet

Dean Monogenis shares Balincourt's Pop Art palette and dispersed points of attention. He also has Castillo's echoes of the Hudson River School. It is a lot to ask of a style close at times to comic strips. But after seeing two shows of his, three years apart, I can see why the echoes fit a trend in just that direction.

He, too, looks everywhere and nowhere, with the city as a fantastic planet in microcosm. He lacks Balincourt's ability to score points quickly, whether politically or visually. Sometimes, however, that can mean more is going on. Stylistically, his hard edges, his compositions centered around buildings, and their frequent disjunctions in scale owe less to expressionism or folk art than to Charles Demuth or Photoshop. He embeds his subject matter more precisely in contemporary America as well.

Here landscape and architecture fight for space while insisting on how well they get along. His paintings place fantasy structures in impossible settings. A mammoth stone wall separates a hillock from the plains, like the political divisions so often latent in geographic expansion. A parachute balloons upward into a night sky, begging to carry a factory with it. Modernist homes float above plateaus or cantilever over mountains inhabited by communications towers. If anyone can bring broadband to America, this will.

The struggle extends to style. The crisp edges, bright colors, and motifs allude to Japanese landscape and cartoons. However, lines and curves also suggest architectural renderings and their digital tools, and they have a way of overflowing the buildings. Perspective drawing and American Romanticism in fact share his preference for diagonals sweeping into the distance. Especially in reproduction, the results get cute fast. At his darkest, however, Monogenis has some of the conflicted optimism of the originals.

Demuth might still recognize the industrial settings, but not the wind farm alongside. Has a green utopia arrived at last, or has the battleground just grown more contested? Are the paintings themselves fantasies or fears, and do they represent the fantasies and fears in a real New York—or offer escape? A title like Another Residential Fantasy could apply equally well to the painting or to Chelsea. Like Balincourt's, Monogenis's ambivalence seems too trendy for its own good, but also skillful and relevant.

Castillo's smooth ribbons and broken edges appeared earlier in her gallery's Brooklyn headquarters. I saw them again more recently in a show of Caribbean art at the Brooklyn Museum. I see not so much pain or hope, but rather one artist in the Chelsea fall who takes responsibility for finding formal patterns even in self-destruction. Monogenis is more optimistic, and Balincourt just more spaced out. Which attitude captures the art scene best? I sometimes hate to ask.

Adam Helms ran at Marianne Boesky through October 6, 2007, T. J. Wilcox at Metro Pictures through October 13, Friedrich Kunath at Andrea Rosen through October 13, Keith Tyson at Pace through October 20, Jamie Isenstein at Andrew Kreps through October 20, Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba at Lehmann Maupin through October 20, Jim Drain at Greene Naftali through October 13, Emilio Perez at Galerie Lelong through October 13, Ingrid Calame at James Cohan through October 13, Jeff Shore and Jon Fisher at Clementine through October 6, Larry Clark at Luhring Augustine through October 13, Brad Moore at Point of Viewthrough October 9, Eva Struble at Lombard-Freid through October 13, Jules de Balincourt at Zach Feuer through October 13, Dean Monogenis at Stux through October 13, Liset Castillo at Black and White through October 13. I silently update Mogenis for his return at Collette Blanchard through May 2, 2010.