In Praise of Dreams

John Haberin New York City

Vermeer and the Delft School

In my dreams

I paint like Vermeer van Delft

Jan Vermeer's one street scene seems at once too distant and familiar, like memory. Like the poem by Wislawa Szymborska that I have just quoted, it seems to speak in praise of dreams.

I speak fluent Greek

and not just with the living.

Standing on a New York sidewalk, I can imagine staring across a street in Delft, and yet how different the results. The five-story building in front of me, not much taller than those Vermeer painted nearly 450 years ago, feels all the more intimate as it rises above my head. Even on a quiet weekend morning, bleached to a dusty monochrome by the sun, it has lost itself in human and inhuman traffic.

Standing on a New York sidewalk, I can imagine staring across a street in Delft, and yet how different the results. The five-story building in front of me, not much taller than those Vermeer painted nearly 450 years ago, feels all the more intimate as it rises above my head. Even on a quiet weekend morning, bleached to a dusty monochrome by the sun, it has lost itself in human and inhuman traffic.

Vermeer takes in entire buildings, but the bright, white pointing ripples between bricks. Together with the window lattices, it creates a fine tracery that builds in intensity as one gazes, figuratively cementing and animating the entire scene. The oils, although darker than one might expect, soak up light as they would the sun, and the emphasis on red and green gives to inanimate objects an association with a living Earth. One could almost mistake distant buildings, just out of focus, for a background of trees. The few living forms, two women and a pair of children, hide in the shadow of an alley, a doorway, or a bench.

The image looks oddly small, intricate, and quiet. The point of view may at first appear superhuman, even false, but it dares one to fault its documentary perfection. It also dares one to relegate it to a moment in Dutch history.

The Met dares exactly that. "Vermeer and the Delft School" argues for the birth not just of a new art, but of a great city. With perhaps fifteen of Vermeer's works on view, almost half his meager output, it sees him as the product and culmination of a young, metropolitan culture. Like much of the awful crowd, I was fascinated, grateful—and not convinced. To see why, let me walk through from the very beginning.

I drive a car

that does what I want it to.

The show opens with an enormous room, suited to the pride and ambition of its contents. A stiff, pompous mix of portraiture and the decorative arts makes sense for a new nation, still to write its great epic, and that is what the Met has in store.

The Dutch republic had gained its independence from Spain. It took a century of war the nation did not so much win as survive. Now Delft's tradespeople asserted their wealth and status with single and guild portraits. Painters, as emblem of their craft, liked especially one theme for group portraiture, the anatomy lesson. In Amsterdam, Rembrandt himself had pulled that one off magnificently.

The Delft example would not have made Rembrandt or a pupil like Gerrit Dou in Leiden jealous. Everyone faces artificially and artlessly forward, the better to be seen. Think of a birthday album now, if a tad more grisly—Nan Goldin for a sixteenth-century homecoming. It should make that Dutch middle-class town entirely familiar.

I felt at home again in the next room, with drawings and prints. Streets like Vermeer's had gone up barely decades before, more went up when a gunpowder explosion leveled blocks, and artists documented it all. I thought of the birth of Manhattan at almost the same time.

Svetlana Alpers, in The Art of Describing, notes how the Dutch loved to map both lands and history. She placed their impulse at the heart of art's newfound realism. Vermeer and others include maps as props within paintings. The blurry buildings in Vermeer's street scene, reflecting a narrow depth of focus, make more sense given another mapping device, the camera obscura, and the Met puts one on display. Over the course of this exhibition, maps and blurs become the one surviving impulse from a more epic style.

I am gifted

and write mighty epics.

The Dutch had fought for freedom of religion. Refugees poured in from the half of Flanders, still under Spanish rule. But did that mean tolerance for all at last or a Protestant nation? Arguments could get nasty, but either way, they made a good excuse for both moralizing and plain creature comforts. The next few rooms show plenty of both.

Among the drinking scenes, Vermeer's may contain a self-portrait. The lavish still lifes, many with emblems of death, match the vanitas theme popular all over the country, but they prepare one for yet other Vermeers. I thought of the props on his many table tops. I thought, too, of an allegory of faith, perhaps his last work.

At the same time, as things calmed down, art got more sophisticated and more intimate. Outsize tales largely vanished. One sees the change in Carel Fabritius, who died in the explosion at age 32. Fabritius, a student of Rembrandt, starts with a brushy and romantic self-portrait—for me the show's greatest rarity and treat. I kept asking myself what rock star he most resembles. In no time, however, he sheds much of Rembrandt's influence, along with the overstatement.

A second self-portrait has blonder, more even tones. A wide-angle scene looks ahead to Vermeer's street in its modesty and concern for optical values. Probably it once curved to fit in a box with a peephole. Having learned well from the camera obscura, art pulls the ultimate trick of simulating one. Fabritius's last small canvas shows no need at all for the human comedy. It has little more than a goldfinch, chained to its perch but seemingly about to take flight.

I hear voices

as clearly as any venerable saint.

Pieter de Hooch starts more and more to domesticate his art, too. He transforms a genre he has inherited from beyond Delft, in Gerard Ter Borch's household scenes. In place of Ter Borch's groping couples, half on top of one another, de Hooch's men and women stand modestly erect, so that their outlines do not overlap. In place of carousing, they sip beer, share a smoke, or tend to children. Colors lighten. Brushstrokes get tighter and more even, like Vermeer's brickwork at around the same time.

The deadpan affection of de Hooch has much in common with Vermeer's, and the cuteness of his maternal scenes extends everywhere. Hendrick van der Burch's badly drawn child reminds me of a space alien, and yet his bedroom comforts him and the viewer alike. ET did go home.

The newfound domesticity extends to perhaps the least likely place of all, the cathedral. Cornelisz van Vliet and Emmanuel deWitte, like Pieter Saenredam, use their new command of light and perspective to make church interiors soar. The life inside, however, has little to do with religion and the sublime. Here lies the bustling city scene absent from Vermeer's outdoors.

While sermons carry on in the background, men and women stroll, taking careful note of the family plaques all around. The tomb belongs to William the Silent, who had led the political struggle. Dogs scratch, rear, and goodness knows what else. Children add stick-figure graffiti to the pillars, without aspiring to postmodern graffiti art. Yet the twin suggestions of defacement, like the brilliant perspective drawing, become emblems for the freshly down-to-earth art of painting.

My brilliance as a pianist

would stun you.

With these changes all around him, Vermeer's growth does make more sense. One gains insight into his technique. One better understands his lifelong stress on the intimate relations between men and women. As one moves through the show, he receives more and more space, until the final room is almost his and his alone. If one has any strength left, a sign by the exit suggests continuing to the Frick, a ten-minute walk, for four more. (The Frick's bylaws prohibit lending these.)

And yet I left unconvinced of Delft's special role. On the one hand, it conflates a city's history with an entire nation's. On the other, it ignores what Vermeer alone does so well. Take each problem in turn.

I fly the way we ought to,

i.e., on my own.

The imprint lies everywhere of greater events and other artists, beyond Delft. I have mentioned so far a few Dutch influences on Delft, but only a few. A Rembrandt imitator, Leonaert Bramer, has more works here than I care to say. An artist from Leiden and the Hague, Jan van Goyen, contributes the most luminous sketch of an emerging skyline.

The importance of other artists goes well beyond influences. All the cathedral views, one after another, suggest the show's limits, too. In a small country, other genre specialists happened to work elsewhere, for no deep reason, and all for the same markets.

Certainly Vermeer did not think in isolation. Financially, he got along as best he could with another job, dealing in art from many nations. Visually, he looked far, too. A larger View of Delft, not on display at the Met, includes water, ships, and all the machinery that connected a city to Europe's economy. In its command of light and perspective, it knows well the Renaissance gains and Baroque course in art and science.

Dutch painting everywhere becomes more introspective around mid-century, and by the end of Vermeer's life the pendulum swings once again. Freedom and community soon lose their novelty, class structure hardens, and new European conflicts call forth a more defensive, more public display. Rembrandt, for all the fame of his his inner-directed art and his work in as commercial a medium as prints, died in poverty. A late return to overstuffed allegory after the enigma of Vermeer's Milkmaid may be a Catholic's deathbed confession—or a premonition of postmodern trends—but it may also make market sense after all.

Even William's tomb amounts to a footnote in a wider story. (Simon Schama outlines it all with too much literary flair for his own good, in Rembrandt's Eyes.) Born in Breda, the man led the fight, but not from a small town like Delft. By the war's end, Spain had placed him under near house arrest elsewhere, too, and his death was a political assassination.

Falling from the roof,

I tumble gently to the grass.

If the Met claims too much for Delft, it claims too little for Jan Vermeer. Walter Liedtke, the curator, places him solely amid the whirlwind of a city's art. The context proves invaluable—but only because it also shows the contrasts between him and his peers. Look at Vermeer's little street again, after catching up with A Courtyard in Delft, by de Hooch.

The latter has something of Vermeer's brickwork and steady geometry, in a façade lying parallel to the picture plane. Here, too, light and shadow fill every crevice, and again one sees no men, only two women and a little girl. They go about their business, with no special story to tell.

Yet de Hooch shows a very different world from Vermeer's, a steady, comforting, and human one. A woman and the girl emerge out of an undefined interior at right, into the light of day. At left, a passage leads from the bright courtyard into an even more sun-drenched space in the distance. The second woman stands in shadow, her back to the picture. She is taking in the sun, leading one's eye into space. As de Hooch presents interiors within interiors, one navigates them with ease, like one's very own home.

Vermeer shows a public space, a space outdoors that belongs to others. One's eye barely penetrates the darkness where women labor and children play. Nothing breaks the frontal vista. If the buildings seem unnaturally small, one cannot fault Vermeer's point of view after all. One is seeing from across the way, from inside. One is in Vermeer's place, in an age before plein-air painting. One is also in the place of his women, looking out a window and hoping for love.

I've got no problem

breathing under water.

The mother and child from de Hooch look at each other with care and love. They hold hands, the mother taking the first step for them both into the larger world. The building itself reaches out to them, its arch tall enough to accommodate them with ease, short enough to guide their steps. The only signs of labor, a broom and a bucket, lie on the ground. They have done their job, leaving hardly a trace of dirt. In another version of the same courtyard, also on view at the Met, the woman gets along on equal terms as she drinks with men.

Vermeer's women huddle in the narrow passage at their work. The children may (or may not) have any connection to the grownups, but they have ventured outside alone. They, too, are bent over to scrounge under the bench. They act apart from unseen others, without ever shaking themselves free. In Vermeer's interiors, women often have that dilemma.

I can't complain:

I've been able to locate Atlantis.

Over the courtyard's central arch, de Hooch places an inscribed tablet, weathered like his brick walls and overgrown by leaves. Trees reach in from over the high wall at right. The courtyard has attractive paving, but probably made up, since it has a different paving in the other version. Nature and culture live at ease together, but then culture—in a household or in a painter's art—gets the upper hand. Claude Levi-Strauss, the anthropologist who ushered in structuralism, opposed the raw and the cooked, as values that help to define a native culture. Has de Hooch cooked up this one?

On Vermeer's narrow street, labor keeps at it without ever winning over the world. In place of de Hooch's spotless pavement, the dusty foreground has rut after irregular rut of wheels. Those distant buildings stay as ill-defined as trees. A reconstruction has verified the accuracy of Vermeer's View of Delft. I bet he has not made up this muddy thoroughfare or its indecipherable backdrop either.

Vermeer documents both nature and culture, because the active imagination never totally makes over either one. Fate will take its unsteady course, like the delicate balance in A Woman Weighing Pearls, or the woman hoping to stand on a ball in the late allegory. Yet art and other ordinary human acts may have the last word after all. The woman never falls off her perch, and the street's geometry glows as even de Hooch's alleyway never can.

Vermeer converted to Catholicism for his marriage. As with the ambiguity of religious freedom in Delft, one will never know if he changed for convenience or from conviction. Did de Hooch's trust in creature comforts come from his Protestantism? Vermeer's dark undertone may well reflect a Catholic's more troubled sense of fate—in doctrine and as an outsider in a war-torn land. I cannot say. I know only that his greatness lies in resisting certainty, even the Church's certainty of doom.

It's gratifying that I can always

wake up before dying.

If I had trouble seeing Delft and Vermeer as a unique whole, so apparently does everyone else. People rush past the dull opening rooms, ignore even Fabritius and de Hooch, and crowd around the Vermeers. The quiet of his little street exists only in metaphor. Even on a weekday morning, the throng can go thirty deep. Yet many of the works sit undisturbed most days in the Met's own collection. The same crowds normally pass by, on the way to another blockbuster.

I can hardly blame them. The Met's habit of long wall labels on each work makes it this bad. While less officious than usual for the Met, Liedtke stops novices from finding their own meanings. Worse still, people cluster in front of the labels more than the paintings, rendering the traffic yet more unbearable. Throw in a docent tour and I would have fled in terror.

Try as they will for modesty and skepticism, the labels amount to summary judgment. For some reason the Met omits one for Vermeer's incredible Woman in a Red Hat, and hardly anyone stops to look. Lulled off, people must take the omission to indicate a minor work.

As soon as war breaks out,

I roll over on my other side.

They had better not get too complacent, however fine the Met's insights. The last room includes a painting rarely seen and not in his Washington retrospective five years ago, a Young Woman Seated at the Virginals. Nowhere else does he combine a lone woman at her table with an undecorated, slightly modulated background. The light on a her face looks way too harsh. Still, historians document the painting within decades of Vermeer's death, when he had no followers.

Vermeer may have painted it, but I may never know. An imitator may have cobbled it together from stock motifs, or Vermeer may have left it undone. The truth may remain forever buried in overpainting. And yet the Met will not admit to the least uncertainty.

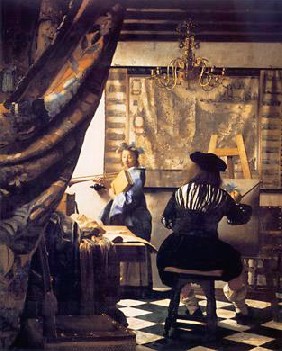

Indeed, the Met has trouble admitting anything that will disturb its narrative. The show ends with the 1668/1669 Art of Painting, entirely out of chronological order. One must be wide awake to notice the disturbance. One must be more alert still to catch the irony, in a show about dates and a city's golden age.

One should stay awake until the end, though, or even arrive first thing in the morning and run ahead of the crowd. The Art of Painting makes for a remarkable conclusion.

I'm a child of my age,

but I don't have to be.

Vermeer's women mostly deal with the threat and fragility of love, with only a hint of an outside world. They dress in the best fashion, and their interiors gain color and drama from the shadows. Flooded in sunlight and dedicated to no more than a painter at his easel, The Art of Painting may seem different—closer to the street scene. Like the street scene, too, however, it creates a theater of its own, with painting never fully outside the picture.

A woman stands in a classical robe, with all the official attributes of the muse. She holds a book for learning and a horn, literally trumpeting the art of painting. A mask, for theater, lies face up in front of her, along with emblems for the remaining senses—an even heavier volume, an open sketchbook, a soft fabric. Yes, a map, part of the artist's command of the world, covers the wall behind her.

The painter, back to the viewer, declares his place among the arts. Contrary to practice, he starts a blank canvas with the muse's laurel crown. Given painting's glory, it is all of the real scene that one needs to know.

At the same time, the painting forces one to see these as two real people, straining to act out their roles. Even here, in a scene out of myth, Vermeer dares one to say that he has invented it all.

The woman looks meekly downward, eyes almost shut, as much in fatigue as in glorious modesty. She rests the book against her, as if to bear its weight. She holds the horn palm up for balance. While bathed in sunlight, she casts a disturbing shadow across the picture's very center. A chair all the way to the right seems far away. I guess she will have to stand.

The map behind her, like the rafters and the tiled floor, reminds one of Vermeer's Dutch interiors. Once again, the scene hold the burdens of choice for a real woman, cut off from power over a wider outside world.

A few years ago

I saw two suns.

The painter, too, cannot quite merge into emblem. He shares the room with the sitter, separated from the viewer by an enormous curtain. He leans forward, his legs bent in the excitement of his work. In contrast to the muse's robe, he wears the black and white of the artisan class. The crisp edges of her robe catch dazzling highlights, but he has to settle for dull shadows. Judging by his stature and frizzy hair, like the man in that early Merry Company, Vermeer may have intended a self-portrait.

The painter's place in this world shows him up a bit, too. His hand, balanced on a stick as in ordinary life, comes off as a blurred oval from its very motion. It looks almost comically like a stump. As Jed Perl points out, the mask of tragedy leaves him hauntingly without a face. One blank, eyeless mask has displaced another.

The story does not end there, however. Another eye sees it all, and another hand captures it to perfection. The painting declares its own mastery after all.

The floor tiles, wildly skewed, show a command of perspective. So does another chair, strongly foreshortened and right up against the picture plane. The stump of a hand even suggests modern photography with a slow shutter speed. The candelabra lacks a single candle, but then it can hardly hold a candle to the Vermeer's skill with textures and shadow. Forget Delft's praise of dreams. Before electricity and modern museums, the illusionist light would have competed on equal terms with the sun.

And the night before last a penguin,

clear as day.

The curtain outdoes any mask as a mark of high drama, only whose drama is it? Is the woman straining to be real or imagined? Are her possessions props, emblems, or even her own? Is the painter displaying himself as a kind of signature, subject, or legend, or is he simply turning his back? As in a poem by David Shapiro, "If students visit for signs / Or signatures we should discuss traces."

One can never say for sure where in this painting painting rests. Like other human labor or love, it cannot get away with a nobler epic, but it comes with imaginings of its own. Like the painter's clothing, it is all there, faithfully, in black and white.

"Vermeer and the Delft School" runs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 27, 2001. "In Praise of Dreams," from Wislawa Szymborska's Could Have (1972), also appears in her selected poems, View with a Grain of Sand (Harcourt Brace, 1995). I had completed my argument before encountering Jed Perl in his online Artnotes for The New Republic, but I should be churlish to rule out any influence from his engaging review. The Web can point one to All About Johannes Vermeer, including what little is known of his life, and to a guided tour of his Delft.