Your Own Private Park

John Haberin New York City

Barry Diller, Thomas Heatherwick, and Little Island

Meg Webster on Governors Island

What if you could have your own private park, in one of New York's liveliest and most touristed neighborhoods? Would you take it, and could you keep it to yourself?

Barry Diller fought seven years for the privilege, but not just for him. He wanted to leave his mark on the city, and he wanted to share the experience with others. The result is Little Island, designed by Thomas Heatherwick—an island of tranquility off West 13th Street, just a stone's throw from the Whitney Museum and the trendy Standard Hotel. It is, at least, for those lucky and determined enough to see it.  A former Hudson River pier has become a public arena and the very image of luxury. It is also a test case of what counts as a public park.

A former Hudson River pier has become a public arena and the very image of luxury. It is also a test case of what counts as a public park.

They are not the only ones out to reclaim the waterfront. Like anyone worried by climate change, Meg Webster can be chiding or hopeful, reverential when it comes to planet earth or fearful for what its fate means for humanity. Emotions that strong can get in the way of art, but not on Governors Island. With Onyedika Chuke and Muna Malik, she helps launch the former LMCC Arts Center with a spiffy new look and new name. They cannot rival Little Island for its pretension and its flair. Take the ferry, though, and you can stay on this island for the day.

This is not a pier

Diller saw a need and an opportunity. Abandoned and in disrepair, pier 54 wanted only Hurricane Sandy to finish it off. The waterfront as a pick-up spot for gay sex, so poignant in photographs by Alvin Baltrop, was a distant memory. As most likely gay, Diller must have found that history hard to forget nonetheless. As an entertainment mogul, starting at Paramount Pictures, he had no end of confidence in his ability to please others as well—although he has since faced charges of covering up sexual harassment. Thanks to his business success and marriage to Diane von Furstenberg, he had no shortage of cash either, and the family foundation picked up much of the tab.

He saw an opportunity in another way as well. The pier lay in ruins, but the Meatpacking District was thriving—at the foot of the High Line, as a new home for the Whitney, and on its own. And a producer like Diller knows when to play to the audience. He also knows how to create one. Capacity crowds filled Little Island from the very day it opened, and why not? You would be curious, too.

From a distance, the park looks lush, exotic, and mysterious, rising on mushroom-shaped pillars (tulips, if you ask Diller) to a dense tract of green. It promises two separate overlooks of the river, plus one of the Whitney, "the Glade." It promises a full schedule of events at its amphitheater, "the Amph," with nearly seven hundred seats. In keeping with an arty neighborhood, they have focused on performance and dance. It promises drinking and dining, and its "sips and bites" beat the choices on the High Line hands down. It promises, too, vistas yet unknown.

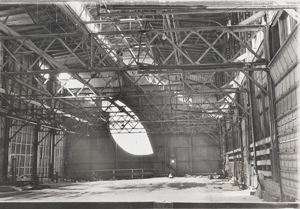

But an island? As René Magritte did not quite say, this is not a pier. It began as one, and wood pilings remain visible in the water. One enters and exits the island via two long passageways, much as one would have walked through a warehouse to the end of a pier. A towering steel gate stands out front, left over from its history, among the park's high notes and a tribute to its site. Yet it is first and foremost a fantasy.

It is a delightful fantasy at that, from its twisting stairs and ramps to breaks in the handrails that tempt one to descend on one's own. The planting is dense, and other materials are luxuriant as well. More rusted steel serves as risers, punctuating the artificial cliffs. While they, too, hint at an industrial past, they look right out of Richard Serra, only less intimidating. The landscape architects, Signe Nielsen with Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects (MNLA), think of the park as a "leaf floating on water." You would not be wrong to think of Christo and his tropical Floating Island.

Its principal architect, Thomas Heatherwick, has experience with fantasies—including a luxury condo a few blocks north in Chelsea, where every single resident has bay windows. Still further north, amid the wealth of Hudson Yards, his tall sculpture invites one to ascend. (It did, that is, until suicides restricted access.) Like that sculpture, Vessel, a tour of Little Island offers a bit of a workout. Join the crowd, and start climbing. Bikers and joggers back along the waterfront will be glad that you did.

Not my backyard

How can I call it an exclusive private park, when it is public ground? Diller meant it all along as a gift to the community. Little Island extends Hudson River Park, and it developed in partnership with the Hudson River Park Trust. It distributes free tickets to the Amph to local businesses, seen as "partners," too. Other tickets are for sale, but the park itself is free. Proper parks always are, right?

It took those seven years because of community opposition, ostensibly over threats to marine life—but when does progress in New York City not run into "not in my backyard"? Still, this is not your backyard one bit, any more than Heatherwick's wealthy customers elsewhere are your neighbors. It can sure feel off-limits, with reservations required after noon. As of June, none were available before dark for the foreseeable future. Little Island is open until one in the morning, but that may not be what you had in mind. I first showed up just after noon, and there were no lines out front, but also no exceptions.

It took those seven years because of community opposition, ostensibly over threats to marine life—but when does progress in New York City not run into "not in my backyard"? Still, this is not your backyard one bit, any more than Heatherwick's wealthy customers elsewhere are your neighbors. It can sure feel off-limits, with reservations required after noon. As of June, none were available before dark for the foreseeable future. Little Island is open until one in the morning, but that may not be what you had in mind. I first showed up just after noon, and there were no lines out front, but also no exceptions.

It looks private, too, with little beyond its underpinnings visible from shore. Imagine that you could see nothing of Central Park from its interior roads or Fifth Avenue. New York has at least one actual private park, Gramercy Park, with keys for neighbors only, but with comforting views for the rest of us from outside. Even more, for all its bows to the community, this island of tranquility is a rich man's private vision. It comes into view as that image of luxury, and that image never lets up. It might have dropped down on the Hudson from many miles away.

Its private vision extends to how the public uses the park. You can meander its 2.6 acres for maybe twenty minutes, but the ramps and stairs lead you every step of the way. There is not a single lawn in which to take the sun. A glade is open space in a forest, but the Glade is not. The dining area is "the Play Ground," but this is not a place to play. Again, that should have you asking what goes into a public park. Is it greenery, space, access, or also, yes also, something more?

When I was a kid, my father would take me "exploring" in Central Park, including its most seemingly unstructured area, the Ramble. I took him at his word, and I loved him for it. In contrast, the High Line is still a forced march along the former rail tracks from one end to the other. That has made it an unmatched success for tourists and a model for other cities, but it is also why New Yorkers mostly pass it up. I am speaking of a park as the chance not just to encounter new experiences, but to create them—if only, as in Europe's great gardens, by slowing up and sitting down. That spontaneity may be an illusion, when Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux as architects saw to every inch of Central Park, but that illusion is their genius.

Little Island opened just four days after another river project barely a block away and not long before another "Open Call" at Hudson Yards in the Shet. (Athletic fields are in progress between the two.) With Day's End across from the Whitney, David Hammons returns to a pier's history as a site for risky behavior and risky art. He does so, too, with the bare outline of a lost warehouse in polished steel, with respect for the past and with nothing hidden from view. Little Island's drawbacks may take care of themselves, as attendance limits fade with the pandemic and New Yorkers grow familiar with what for now they cannot see. The park deserves its crowds, but I am not yet ready to call their fantasies my own.

A wave in New York harbor

Meg Webster has recorded polar bears on the verge of extinction for their own sake as much as for their lessons. Her mound of earth in Socrates Sculpture Park approached an ancient pyramid while harboring life. Her pool bubbled up from one level of MoMA PS1 to another as if were more natural still. New York City might seem like the last place to encounter earth art, but think again. It cannot cross entire lakes or deserts, but it adds the dimension of time.

When it comes to earthworks, one never can fully separate art from its habitat. One can only hope, as with the usual range of human activity, not to bury nature alive. Now Webster fills a gallery with what might pass for a single ecosystem, but it comes from all over the northeast and spills out into more as well. It also gives a taste of her varied media in work from more than twenty years. New Yorkers might be desperate to get away on a summer weekend, even to a former military base with artificial hills on its carefully landscaped south end. They might welcome a show called "Wave," at the Governors Island Arts Center.

Here, too, she includes video, of Houston Brook Falls in Maine as a reasonable substitute for a wave. She has another mound, Moss Mound, on a human scale but not so tall as to cut off the view. She pipes in birds and other sounds from Hutcheson Memorial Forest in New Jersey. What I took for paper cutouts of more birds are white flowers, flourishing in a long tray under growing lights. She took their seeds from across the region, as Growing Piece, and will transplant them elsewhere before she is done. I cannot swear how blown glass spheres relate to ecosystems, even with indented tops like apples, but they fit right in.

For all her strong feelings, only a second installation gets preachy. In fact, it centers on empty pews from a Quaker church. They break up a gallery, like barriers in a maze. They also frame sculpture, including the fallen head of Hercules and the winged feet of Hermes in a pool of soapy water, surrounded by enormous bones. Had she stopped there, Onyedika Chuke might have created a space for reverence, but she throws in video of Ronald Reagan's "war on drugs," which did so much to fill prisons—and an explanation that the soap comes from prisons, too. She calls it The Forever Museum Archive_Circa 6000BCE, and who knew that naming conventions from social media go back eight thousand years?

The arts center has long had a studio program near the Manhattan ferry landing, and it seemed promising when it reopened in 2019 as also a gallery for the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council (or LMCC). Reopened again in June after the lockdown, it looks cleaner and more spacious still. Its two floors have only small shows, but of big work. With room for Joe Coffee, you can at least count on art to keep you awake, but no: that is not a fourth artist, but a coffee shop, with space to sit. Besides, one enters downstairs for coffee past a large sculpture, visible from outside, that would draw anyone in.

It also continues Webster's concern for the future. Inside, in the round, it looks more obviously like an origami boat, only in glass and steel. One could imagine climbing right in and going places. Muna Malik, though, sees it as only part of a "participatory installation," Blessing of the Boats. It comes with paper and instructions for you to make your own—and with her saccharine hope that you will add your blessings for the planet. Her boat, like the summer's art itself, serves as a receptacle.

Little Island opened to the public May 21, 2021. Meg Webster, Onyedika Chuke, and Muna Malik ran at the Governors Island Arts Center, formerly the LMCC Arts Center, through October 31.