Reclaiming the Streets

John Haberin New York City

Life Between Buildings, Designing Peace, and Duke Riley

Does New York still have room for life? "Life Between Buildings" brings a touch of humanity and greenery to Long Island City, but neither city planners nor commercial developers, it insists, can be trusted with either one.

Not all that long ago, the city struggled with what MoMA PS1 calls the "interstices" between buildings. In response, artists value vacant lots and air shafts as much as parks and busy streets—and sees in them a greater potential for community. If that sounds utopian others would embrace the charge. "Designing Peace" at the Cooper-Hewitt asks what architects themselves can do. Last, out in Brooklyn, Duke Riley laments the loss of another green space, New York waterways, but he turns the loss into art. Like a community garden, they give new meaning to urban design.

Empty lots or pristine parks?

New York can be a hard, cold place—a place of concrete, glass, and steel. Not, though, for Gordon Matta-Clark, who imagined Hit and Run Gardens for empty lots, sunlight pouring into abandoned piers, and a rosebush for the church of Saint Marks. Not for Mel Chin, who planted native species on a triangle in Chinatown, at the foot of the Manhattan Bridge. Not for Cecilia Vicuña, who designed Sidewalk Forests for Tribeca—or Becky Howland, who left bundles of grass nearby to catch the light. And they kept at it for more than a decade, starting with Matta-Clark in 1971. But could they offer an alternative to a faceless city?

Not everyone will see grounds for hope in such barren ground, and not everyone will see a need. What of parks and botanic gardens? I grew up with them, as places to play and to learn. I discovered hidden pockets of nature and New York. I discovered running in the evening and Shakespeare after dark. I discovered sunlight at dawn and, ultimately, myself.

Still, those discoveries exclude others, and they come at a cost. Frederick Law Olmsted had to accept the destruction of a Native American village and the displacement of African Americans to make room for Central Park. Closer to the present, Madison Square Park has made itself a destination for sunbathing and summer sculpture—but only because of wealthy neighbors and private patrons, while less privileged neighborhoods go without. They must rely on themselves for whatever they can get. And there the city may be no help at all. It may go so far as to bulldoze their plots, leaving what Poncili Creación calls "capitalist rubble."

Creación commemorates destruction, with pretend bronze plaques after real claims to private property—as does Niloufar Emamifar with a plank rescued from a lot in Brooklyn. David L. Johnson documents "adverse possessions" (seizures, to you) and Margaret Morton the homeless, bereft of their encampments in Tomkins Square Park. For Matthew Schrader, destruction means the loss of an ecosystem, with the Ailanthus tree, or "tree of heaven," presiding over depleted soil. For Danielle De Jesus, it is a matter of racial justice, as Nuyoricans watch their gardens utterly vanish. I could dismiss all this as back in the days of Mayor Giuliani, before his still more egregious conduct under Donald J. Trump. Aki Onda, though, tracks continued abuse of power in the pandemic.

Are they too pessimistic? Big parks take funding, but they welcome tens of thousands with discoveries to make and nowhere else to go. Art in Socrates Sculpture Park serves the community as well—like a BBQ pit by Paul Ramirez Jonas that is living up to its name, Eternal Flame. When Tom Burr plants a wild garden in the Ramble in Central Park and "Architecture Now" at MoMA settles for pocket parks, they could be carrying coals to Newcastle. When POOL (or Performance on One Leg) in the early 1980s does its thing on landfill that later became Battery Park City, it subverts plans for luxury housing. Yet its performances look lame and ego-driven compared to land art by women like Agnes Denes yet to come.

Or are they too optimistic—like Burr in 1992 glorifying a gay pickup spot just as AIDS took its toll? Local gardens may only indulge an individual, often white, with locked gates for little more than weeds. jackie sumell and the Lower Eastside Girls Club hope to make a statement with their greenhouse on the scale of a prison cell. Yet it rests behind thick walls in the museum's pebbled courtyard, where nothing will ever grow. Art has always had its dreams of "Back to Eden" and "The Machine in the Garden," and here they come again. Welcome them, but expect only so much.

Signs of hope

"How can design support a safe, healthy, and respectful environment? How can design search for justice? How can design search for peace?" Oh, just asking. Seriously, though, how can it not, and "Designing Peace" finds idealism everywhere, across oceans and from the streets of New York to classrooms in the American South. Can it, though, bring about real or lasting change?

The Cooper Hewitt, which poses those questions, touches on pretty much every hot-button issue for a tense time. That alone holds out hope, and so does its stature as the Smithsonian design museum. If the federal government cares about racism and police violence, MeToo, and the costs of climate change, who can stand in the way of change? Still, the air of extraordinary virtue is no accident. These, the show implies, are not the questions asked every day. Governments and private developers have something else in mind, such as national interests and profits.

The Cooper Hewitt, which poses those questions, touches on pretty much every hot-button issue for a tense time. That alone holds out hope, and so does its stature as the Smithsonian design museum. If the federal government cares about racism and police violence, MeToo, and the costs of climate change, who can stand in the way of change? Still, the air of extraordinary virtue is no accident. These, the show implies, are not the questions asked every day. Governments and private developers have something else in mind, such as national interests and profits.

Maybe not, but they are persistent questions all the same. Dreams of garden cities, concrete utopias, and planned communities have been around as long as anything resembling architecture as a profession. They appear yet again in "Life Between Buildings. Religions and nations have claimed dreams of peace and justice for themselves as well. The museum, though, gives short shrift to history. It wants to stress the urgency of good design now.

It opens with a mural in Harlem on behalf of Black Lives Matter and a live map of sexual harassment. Then come topics less in the headlines but still newsworthy—better libraries, an apartment tower as a Stone Garden, a revival of Korea's Demilitarized Zone as a space for living, and "paper monuments" by children to step in where Confederate monuments have fallen. World peace is not something that you can do from home, not even if your name is John Lennon or Yoko Ono. And these are public projects, with collective authors. That mural alone stretches three city blocks. Several are computer savvy as well, like the unfolding story of an abused and murdered child.

The Stone Garden is gorgeous, ample windows punctuating its textured wall of white and yellow stone. Others are routine, like a "peace pavilion" in India. Some are simply playful, like a "teeter-totter wall" between Mexico and New Mexico, in place of Donald J. Trump's more ominous border. One of the most tantalizing is downright puzzling. Its blue spheres tumbling across the central gallery have something to do with "Christmas operations" and the plight of the demobilized in Colombia. An heir to native textiles in bullet casings sounds more appealing than it is.

Maybe there is no one right way to design for peace, not when markets can co-opt the most forward-looking style. The windows in Stone Garden bring warmth to private enclaves, while a garden for African ancestors in Charleston prefers a more open meeting place by the sea. Maybe, too, architecture can do only so much. Its true value may lie in the activism that enters in. Are some here little more than branding, like a design competition for an emblem of extinction? The entire exhibition may be short of design solutions, but it proposes, literally, signs of hope.

Just one word

"I just want to say one word to you. Just one word." You surely know what is coming, plastics. In The Graduate, the 1967 film, that one word epitomizes the emptiness and comedy of an older generation. Nowadays, plastics epitomize what has gone wrong with nature, but Duke Riley is cleaning house. He converts what he has salvaged into art objects, and a warning born of anger and despair becomes a labor of love.

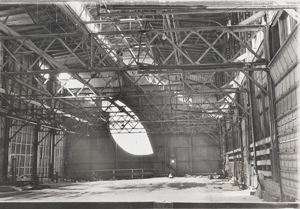

Riley is not your average beachgoer. Where some head for Long Island and New Jersey to bathe in summer, Riley sticks around for the Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek—narrow waters that, he must remind you, are Superfund sites. He joins fellow travelers who cannot afford to flee the city, too, along Jamaica Bay. Yet even there he is not indulging his dreams of pristine sands and seas. He is collecting trash, like Edward Burtynsky in photography, as a work of art and a warning to others about toxic waste. Either one may win out, for its own sake and for its window onto history at the Brooklyn Museum.

He fashions tampon applicators into bait, in colors that a real squid could only envy, and he has caught his share of fish that way, in both senses of the word fluke. He turns one washed-up item into a flamingo, like lawn decoration repurposed for colonial housing. More often, though, Riley retains the shape of plastic containers in off-white, as a surface for portraits and other drawings. They take after scrimshaw, the carved bone with which whalers once filled their spare time and its deficit of beauty. If the show sounds like a period piece, the curators, Liz St. George and Shea Spiller, give him the run of period rooms, too—once home to Dutch settlers in Brooklyn's Mill Basin and Canarsie. A lighting fixture becomes a "boozelier."

Not that plastic has an exclusive on ruining New York's waterways, not even in a time of climate change, water scarcity, and tree loss. On film, researchers describe their first encounters with Newtown Creek, on the Brooklyn-Queens border, where anything flows. Riley himself gives the look of early American painting with alligator teeth and bullet casings for its frame—and the ship it displays is sinking. He recreates the embroidered folk art of "sailor's valentines" in goodness knows what else. If everything here comes in scare quotes, you should be scared. As the exhibition's title has it, "DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash."

Smirks run though almost every title in his evolving Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum. I shall spare you the worst. Still, his eye to past forms is genuine, and nothing should scare you off. A Semi Subjective Map of the Glorious Gowanus from Colonial to Post-Industrial Eras makes the most of three large sheets of fine paper, and the canal's glories extend to mermaids and buoys—while Spode china from the museum's collection looks just fine alongside pretend scrimshaw. A second video shows Riley at work, as artist and environmentalist, and he takes those roles seriously. He also cares enough about the past to mention that Canarsie takes its name from Algonquin peoples.

The show ends on a low or high point, depending on your fears. On Fishers Island off the coast, so much plastic has washed ashore that the sands look like Pointillism or a colorful abstraction. As a resident walks in slow motion through the woods, plastic snow fills the sky. Here in New York, those living near toxic waters know the stench and the rats, but the Gowanus has become a destination for its eateries and a brewpub I keep meaning to try. If Riley soft-pedals contemporary issues, including the fashion for trash as assemblage, he idealizes a time of colonial merchants as well. Still, if art means getting the message out there and making it an enduring memory, his is a non-biodegradable success.

"Life Between Buildings" ran at MoMA PS1 through January 16, 2023, Duke Riley at the Brooklyn Museum through April 23. "Designing Peace" ran at Cooper Hewitt through September 4, 2022. Related reviews look at garden cities and unbuilt architecture.