A Child in the Garden

John Haberin New York City

Isamu Noguchi and Saburo Hasegawa

Gabriel Orozco at the Noguchi Museum

As a child, Isamu Noguchi may never have known where to call home, but his mother cultivated his artistic bent by putting him in charge of their garden. It would be nearly forty years before he returned to Japan as a celebrated artist and architect.

That trip in May 1950 came at the start of Noguchi's finest years—and the peak of postwar American art. It also gained him a guide and companion in Saburo Hasegawa, a writer and artist who had already championed his work. They could exchange memories of Japan and Paris, and they could ponder together the meaning of Japanese written characters for clues to their place within eastern or western tradition. Before long, Hasegawa followed his new friend to New York and settled for good in San Francisco.  Along with its usual serenity and bountiful display, the Isamu Noguchi Museum pairs their work from the early to mid-1950s as "Changing and Unchanging Things." It cannot make a huge case for a collaboration, just as a smaller show cannot make the case for Gabriel Orozco as a Japanese artist, but it does bring out Noguchi's long journey home.

Along with its usual serenity and bountiful display, the Isamu Noguchi Museum pairs their work from the early to mid-1950s as "Changing and Unchanging Things." It cannot make a huge case for a collaboration, just as a smaller show cannot make the case for Gabriel Orozco as a Japanese artist, but it does bring out Noguchi's long journey home.

No end of teachers

Even that first garden soon gave way to life in a largely American community in Japan. And only with Noguchi's death in 1988 could part of his New York studio become solely a garden museum. Even now, it allows an adult to feel at heart a child. It builds on a 1920s industrial building near the waterfront in Astoria, in Queens, a few yards from Socrates Sculpture Park, while uniting its two display floors, mezzanine, and walled sculpture garden as a single space open to the light. Like the Ford Foundation, it creates a rare island of calm in midtown New York by bridging indoors and out. One can take the artist's serenity so for granted, as a product of late Modernism and Japanese tradition, that one can forget what it took to attain.

Born in 1904 in LA, Isamu Noguchi had no end of teachers and friends. He needed them all, as for him there was no there there. His Japanese father invited his unwed American mother to Tokyo, but he had already proposed to another woman and then married a third. That left the boy on his own apart from his supportive mother—and then, as a teenager, far apart from her as well. Sent to high school in the Midwest, he found little encouragement as an artist. A mentor in Indiana introduced him to the sculptor who carved Mount Rushmore, but who could not be bothered to train the young man in his craft.

That same mentor later brought him to New York, where he discovered cutting-edge galleries, like that of Alfred Stieglitz. Still, he stuck to old-fashioned portrait busts until he broke away in 1927 to Paris. There Constantin Brancusi took him on and opened his eyes to abstraction. For the rest of his life, Noguchi excelled in his care and diversity of materials. Alone among the great postwar artists, he also retained Brancusi's allusive abstract forms, rough and polished surfaces, marble and wood, and their place on the ground. To the end, he was still taking modern art off its pedestal.

A late starter, Isamu Noguchi also had to wonder in Paris where to go next. Was he American, Japanese, or an exponent of an art above time and space? Was he still modern at that? He could finally take a close look at his Japanese heritage on a trip to Asia, although his father barely agreed to a meeting. Back in the United States, he felt that he had to prove his patriotism in wartime, but he entered internment as a Japanese American anyway. Back from the camps, he found that art and society had changed.

Japan nurtured his interest in landscaping and, by extension, design and architecture. Now he took up commercial work with Charles Eames and others in furniture. At the same time, he met artists who were working their way to abstraction by a different route, through Surrealism. He found a friend and fellow traveler in Arshile Gorky. He still stands outside Abstract Expressionism, with its breaches of decorum, and David Smith, with echoes of the auto industry, but he does add to his repertoire aluminum and steel. He becomes bolder, simpler, and often more colorful without sacrificing his serenity and or his craft.

Japan had changed, too, although Noguchi has little in common with the postwar whiteness of Mono-ha in sculpture. It was no longer an imperial power, and he was now famous in his childhood land. He exhibited in a department store and found a greater welcome from his father's family after his father's death. He also found another biracial artist in love with Modernism and tea ceremonies. Two years younger than Noguchi, Saburo Hasegawa could introduce his friend to a postwar Asian metropolis, but who can who say who was mentoring whom? The Noguchi Museum treats their work as a collaboration, even after Noguchi settled back into his garden and Hasegawa moved on.

Leaving nothing behind

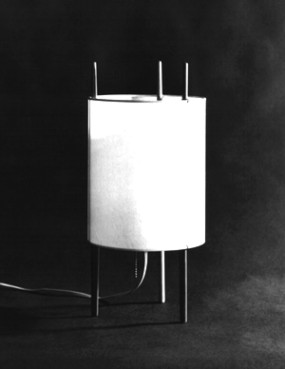

Hasegawa has the walls for his ink on paper, while Noguchi fills the space in-between. Both make clear their abiding interest in Japanese art—Hasegawa with calligraphy and, at times, broad borders or folding screens. Noguchi has his paper lanterns and a fragile wood vase for long-dried flowers. Bird Song adds beaks to Brancusi's Endless Column, while Bell Tower for Hiroshima suspends dark terra cotta from slim wood close to bamboo. At the same time, both artists are staking out a place within Modernism. Pregnant Bird comes even closer to Brancusi, this time his Bird in Space, while that bell tower draws on Surrealism for its darkness.

Hasegawa is plainly the lesser artist, but he may well have looked further ahead. Eco Sum Via Verita quotes the Gospel according to John ("I am the way, the truth"), while its tracery, like that of late Jackson Pollock, never quite settles down into a body or face. Yet ink stains in the shape of brush marks have the spare geometry of Minimalism to come. Other marks approach text painting, with characters in the western alphabet. But then Noguchi titled his work in English. Who can say what counts for him as a first language, if not art?

A show hung this densely is an embarrassment of riches, if not an outright embarrassment, but that alone attests to Noguchi's diversity. All his materials are here, along implicitly with their ancestors. The largest adopt bronze or aluminum, in angled and pockmarked planes not so far from David Smith after all. They pave the way for his public sculpture of the 1960s, but without its turn to bright red. Just a small gesture can turn one motif or material into another at that. Cord wraps raw iron for Calligraphic, while five bronze elements on the floor could be puddles or stones from that long-lost garden.

A show hung this densely is an embarrassment of riches, if not an outright embarrassment, but that alone attests to Noguchi's diversity. All his materials are here, along implicitly with their ancestors. The largest adopt bronze or aluminum, in angled and pockmarked planes not so far from David Smith after all. They pave the way for his public sculpture of the 1960s, but without its turn to bright red. Just a small gesture can turn one motif or material into another at that. Cord wraps raw iron for Calligraphic, while five bronze elements on the floor could be puddles or stones from that long-lost garden.

Noguchi has to have the last word. The show takes up the second floor, so one approaches and leaves via his greater achievement and mostly later work. (The museum does have work from his time in Paris, before his first New York solo show in 1930.) How bold it looks even today—all the bolder for its continued touch with eastern and western tradition. An earlier review tries to keep up after multiple visits to Queens and the Whitney Museum's 2004 Noguchi retrospective. My attempt to fit so many experiences into a tidy narrative leaves it too meandering and too clever by half, but check out the link for more.

This time I decided to start over, just as Noguchi could keep starting over without leaving anything behind. How long it must have taken him for each polished marble, and how long it took to find a balance between serenity and brute mass. They stand out in craggy surfaces, like weighty stones in a Japanese garden, sometimes within the same stone as polished ones. It stands out, too, in the stone's variegated colors, like that of a large, thick ring standing on edge. It may stand out even more in his disruptions of a tidy creation, as with the small pouch waist high on the pregnant bird. Another ring, this time on the floor, slowly rises and refuses to close.

How did he find that balance? For all the father figures, he always had his mother, a writer who began to catalog his work. He also had that questing amazement. He took plenty of photographs on that trip to Japan, including photos of the Katsura imperial villa that became a model for those apparent puddles or stones. The show's handout has him kneeling by a lake in Japan, wary but wide-eyed and smiling. He knew what he had to do as architect of his career and garden museum.

Out for a spin

Gabriel Orozco had a long way to go to recover Japanese tradition. Born in Mexico, he has rarely strayed far from the east or west coast of the United States. If that sounds like the art scene, he had his midcareer retrospective at MoMA as long ago as 2009, plus an installation at the Guggenheim three years later. Even then, he was not going anywhere fast. The retrospective included an elevator with buttons for just the museum's first floor. Yet he appears at the Noguchi Museum with a title that insists on perpetual motion, as "Rotating Objects."

Maybe he traveled by whale—or with a school of whales. He suspended one whale from MoMA's atrium, covered in countless pencil traces. It resonated with anyone with a childhood memories of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. It also showed that he could leave his mark, along with those of a successful artist's studio. It showed, too, that he could master memories other than his own while taming a stubborn museum space. Now he has two small rooms half a floor apart for just a handful of spare works, but he is once again stepping out.

It took Noguchi multiple journeys to get in touch with his ancestors. Orozco needed only a 2015 residency in Tokyo to step outside his. The museum calls its concurrent show of Noguchi and Saburo Hasegawa "Changing and Unchanging Things," but nothing much here really changes. ("Rotating Objects" may recall a museum's display of its permanent collection, where nothing much changes either.) One body of work appropriates fragments of kimono sashes as Obi Scrolls. The other wraps just seven slim wood poles as Roto Shaku, from the Japanese word for standard lengths of lumber.

The changes are telling nonetheless. Surrounded by larger fabrics hung on walls and rolled at their end around poles, the sashes become Japanese scroll paintings. Their floral and landscape patterns fit right in.  A few silk threads add a provocative intrusion into the third dimension while linking the whole to the current fashion for textiles as paintings. Colored tape wraps the poles in more variegated geometric patterns. Orozco also keeps changing his mind about the orientation of the poles and their groupings on facing walls, turning tradition literally upside-down.

A few silk threads add a provocative intrusion into the third dimension while linking the whole to the current fashion for textiles as paintings. Colored tape wraps the poles in more variegated geometric patterns. Orozco also keeps changing his mind about the orientation of the poles and their groupings on facing walls, turning tradition literally upside-down.

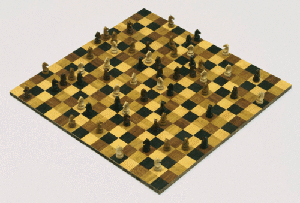

Like Noguchi, he plays with recent generations of Western art, too. His retrospective included a chess board with knights only running wild, a playful homage to another chess lover, Marcel Duchamp. Here the rods allude to paper and fabric wrappings as gifts in Japan, but also to Minimalism. Leaning wood up against the wall has been a staple since John McCracken with the California "Light and Space" movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Lubaina Himid leans dozens of plain rods at different angles at the New Museum. Born in Zambia and part of London's Black Arts Movement along with Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Himid evokes the slave trade in their collective rhythm, like an ocean wave, and their collective shape and materials, like the hull and timbers of a powerful ship.

As ever, Orozco upsets things only so far. The tape patterns are suitably minimal, but arbitrary. The scrolls are only modest substitutes for the real thing. Both series come most alive up close, where the plastic tape seems brutally contemporary and the silk threads like soft stitching for an open wound. The artist is still indulging in a culture that he can never call his own, but Noguchi would understand. At his studio and museum in Queens, he was still a child in the garden.

Isamu Noguchi and Saburo Hasegawa ran at the Isamu Noguchi Museum through July 14, 2019, Gabriel Orozco through August 11. Lubaina Himid ran at the New Museum through October 19. Related reviews look at Isamu Noguchi in 2001 and on his museum's fortieth anniversary, Gabriel Orozco in retrospective, and Noguchi's planned memorial to the atomic dead.