Going to Extremes

John Haberin New York City

Extreme Existence

Gallery-Going: Brooklyn, Fall 2002

After a horror, comes grieving, then rebuilding, and then what? One wants everything to have changed and nothing, life exactly as it was and an obligation never to forget. Art has the same conflict, perhaps more so. Artists get sappy, too, and they cannot stop thinking and acting.

Take some shows that for the most part, frankly, have nothing in the least like politics in mind. I have only myself to blame if I saddle them with my second thoughts over 9/11. Yet they range from begging for sincerity to a mix of ritual and performance, from giving up art to finding that artist acts much the same wherever she goes. Consider "Extreme Existence" and shows by Deborah Masters and Karen Dolmanisth. For Bob and Roberta Smith, however, art just has to carry on—in more than one sense of the term.

Beating a dead horse

Each September 11 now has one assessing what remembrance can mean, much less how it should appear. One can ask how the very notion of art as a memorial has changed, from outcries over the Vietnam War Memorial years ago to plans for Lower Manhattan now.

Only then what? Over the summer, artists and architects had responded, and I, too, have pontificated more than my desserts. I had been there, done that. I can move on now, and so naturally art must, too. I have nothing more to say, and gallery-going will not ask for more, right? Just to see artists still responding—or, just as bad, still refusing to respond—comes as a rude awakening.

It hardly helps, but one has not known for some time whether art is up to anything new. If not, one no longer knows whether that leaves a consensus about the old. One hardly knows, for that matter, whether one should care. Even suppose that art provides a means to grieve, to rebuild, to change, and to remember. Then which of them am I seeing this fall?

At least one person thinks that the times demand a return to sincerity. Does that sound like an aging hippie, still hoping to let it all hang out? Klaus Ottman despises the 1960s, for him a time of irony and cynicism, a time when art "lost its actuality." Now, Ottman demands a return to what existentialists called "the human condition." In putting together his group show, he hopes for an art of "Extreme Existence." And he does not mean werewolves from David Altmejd camping out in Central Park.

Know one sure sign of a bad critic? Whenever I read hysterical complaints instead of understanding, judgmental adjectives instead of interpretation, I know to look elsewhere. I hear only Postmodernism's desperate struggle to stay halfway alive by beating Modernism into a dead horse.

If Pop Art and Minimalism did nothing more than deride mass culture, one could hardly call that cynicism. The anger of the 1960s spoke bravely against something real and urgent, perhaps far more so than the abstraction of existentialist anxiety. However, the language of protest cannot begin to tell the whole story. One cannot reduce the lush abstractions and loving photorealist portraiture of Gerhard Richter and Richter's late work, the visceral lead prop pieces and rusted steel of Richard Serra, or the joyful Mickey Mouse and later brushstrokes of Roy Lichtenstein to parody. One cannot step back from Minimalism in mockery, not when it invites every viewer to experience art as the theater of one's own life.

So much for sincerity

Faced with collage narratives of art and death from Robert Rauschenberg or Larry Rivers, one hardly knows to laugh or to cry. When Frank Stella calls for spatial relationships instead of meaning, he echoes any artist sick of critics reducing everything to words. Only Jasper Johns can better resurrect an art of the Old Masters. Or as Bob and Roberta Smith put it, "Make your own damn art." Be very careful, or I shall.

If anything, it is sincerity that has aged worst, just when artists not far away are discovering naked flesh. Thankfully, one has only to see each new show to rediscover the connection between intellectual puzzles, an artist's methods, a viewer's space, and feelings. By that standard, the irony of Ottman's protest lies in its distance from the present. He may have stumbled on a more extreme anxiety after all.

For one thing, these artists can hardly turn on the past, for they all worked in the bad old days, and Ottman's plea has nothing to do with a return to painting. The show includes the very first video by Chantal Akerman. Nor do these artists prefer Theodor Adorno's "isolated inwardness." Back in the early 1990s, Lucy Gunning hoisted herself up on shelves and door frames to crawl around a barren apartment. She has way too much humor—and too little furniture—to worry for long about the human condition. Her vision of isolation comes with a super deal on a studio, plus a video camera.

Besides, "Extreme Existence" has an odd way of reinventing presence in place of cynicism. Marc Quinn's cool, silvery orbs lie about, as if to market sperm and human tears for the wealthy. This Young British Artist already gained passing fame by selling samples of his frozen blood, as only the collectors and curators melted.

Tania Bruguera in her opening-night performance leaves behind only a rope braided for climbing, strands of her hair, and taped audience responses that one no longer hears. The next day the museum taped visitor reactions to disembodied voices from the first night, the third day thoughts on the second day's empty set and voices, and so on. By the time I got there, one could hear only absent voices talking about the absence of voices talking about an absent performance about, well, I give up.

Like Ottman, can I be watching art-world rituals and mistaking them for the real thing? Two more Brooklyn artists have collaborated on the search for Sacred Matter, and they may well have found it. Together, they demand that viewing give way to participation in a shared experience. It serves as a reminder that, for all the plans and all the voices raised, stories of ritual and remembrance have not ended. Artists are going to keep at this. Another artist I saw that day, Beth Campbell, already has.

From ritual to performance

Deborah Masters places "altars" around the room, each a mix of odds and ends, twigs and branches, and Catholic imagery. I thought of gussied-up versions of the human tendency to hold on to any fragment in a disaster. I thought of a return to Earth in search of values that may well have blown away past recovery. I thought, too, of the trend toward the clutter of found art, from Damien Hirst, as he hires his London gallery's janitor to throw out his own installation, to Jim Shaw's "Thrift Store" paintings, here in Chelsea, too, this fall. Hirst and his dealer fooled the BBC, and his move to the auction houses has fooled others as well. Maybe Masters will have fooled a cold-hearted unbeliever like me.

Sometimes, the participants get to take over the ritual. In the center, suspended from the old, half-rotted industrial wooden ceiling, large clay heads wear long sheets, like robes. They make up a whole family, including a dog. I found the care and scale affecting indeed. Even better, Karen Dolmanisth's circles of sand and mud manage to bring earthworks inside a gallery. They may connect, too, to the circle used at Ground Zero on the anniversary of the killings.

Although the show had opened the day before, Dolmanisth was still installing the work with her feet and bare hands, happily ignoring me. Just in case I thought her work entirely site and time specific, up on the gallery mezzanine a video shows her doing much the same elsewhere—only then not while talking on her cell phone. At what point had the work gone from installation to performance? I have no idea, and that is what creates such a nice space between entropy and ritual.

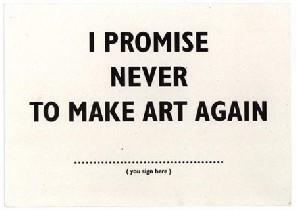

Still convinced that art must now grow silent? Bob and Roberta Smith would surely agree. "Pack it in," demands their "call to Artists." Just sign a card, "I promise never to make art again." One gets in return an amnesty from all the bad art one has ever made. Maybe the Smiths made plenty before Patrick Brill, an English artist, adopted them as his pseudonym.

One deserves as much as an amnesty, judging by the barrage of posters, for even famous names could stand a little time off. The Smith's colored paper, reminiscent of third-grade art class, makes no excuses for artists dead or alive. "Giorgione is rubbish." A red slashed circle, like a no-smoking sign that may become a New York trademark, covers the black silhouette of a dog taking a poop. The Art Amnesty dedicates that one to "Bill"—William Wegman.

Those signed cards spill over the spaces in between. Brill has contributed most of them, I bet. After all, he has no trouble inventing an identity as the Smiths. His pseudonym, promises his gallery, matches the most incisive critic for The New York Times purely by coincidence. But then, that promise did go out to the press. Perhaps he fears that critics will demand that he follow his own advice. He should, after all, have a rich future without art. He could try stand-up.

"Extreme Existence" ran at Pratt Manhattan Gallery through November 16, 2002, Jim Shaw at Metro Pictures through October 26, Deborah Masters and Karen Dolmanisth at Smack Mellon through October 5, and Bob and Roberta Smith at Pierogi through November 11.