Beyond Blackness

John Haberin New York City

Frank Stella: A Retrospective

When Frank Stella made his name with his "Black Paintings," in 1959, would anyone have believed what his art has become today? Would he?

Not "pure painting" by any means—or even, he himself might have said, painting. He seemed at the time to have secured a place for painting, while stripping it to its essence. Now unpainted aluminum and steel practically fly off the wall, in directions set by little more than gut instincts and their own energy. One large painting leaves the wall behind entirely, in gray shards that seem to corrode or to crumble before one's eyes.  Allusions and illusions abound. An artist loved and reviled as the great white hope of Modernism starts to look decidedly postmodern.

Allusions and illusions abound. An artist loved and reviled as the great white hope of Modernism starts to look decidedly postmodern.

But was he there all along, and has he ever left formalism behind? "What you see is what you see," he once said, and everything that goes into the work is still right before your eyes. So is the macho spirit that alienated many a critic from him and from modern art. Yet Stella's outsize gestures comport with a very human sense of his limits. He worked just as philosophers and artists alike were pursuing logical foundations, only to find logic dissolving into paradox. A retrospective shows him asking again and again what counts as painting and never satisfied with the answers.

In your face

The Whitney poses the dilemma of past and present from the start, and it does not need to reach all the way to the beginning and end to do so. The entry wall has a candidate for Stella's largest work to date. Das Edbeden in Chile (or "the earthquake in Chile") from 1999 packs in everything without once leaving the canvas, including illusion, space, and gesture. Spray paint in neon colors peeks out from the edges, behind abstract shapes and grids twisted like the underpinnings of architecture in motion. It has room for text, too, with its title in block capitals at the bottom center of its more than forty feet—a reference to an actual but no longer recent event. This is not about reportage, but about shaking things up.

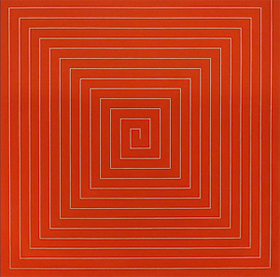

It dwarfs the square painting to its left, no small potatoes itself. The broad, nested bands of Pratfall, from 1974, show not a trace of anything beyond the picture plane. They march from white to gray and back to white, before adding a surrounding band of black. The painting's only frame is its edge or the paint itself. From Stella's "Mitered Maze" series, it also reflects the mitered construction of many a stretcher. Things do not get any simpler or more logical than this.

They do not, that is, unless one reaches back to his very first paintings in New York, from 1958. There the parallel bands stick to at most one color, as for Rosemarie Castoro back then, plus black. Drips appear, not to accommodate the artist's design and gesture as with Jackson Pollock, but because Stella applied paint to canvas on the wall, and it dripped. And then, with the "Black Paintings" in oil and enamel, even the color disappears, along with anything apart from the horizontal and the vertical. Robert Rauschenberg had turned to assemblage, with his combine paintings, and Pop Art had turned to silkscreen and to popular culture. But Stella was going nowhere—and nowhere had never looked so striking or so bold.

So what happened? Ever since, people have been looking for a point of departure and taking sides. Was he too reductive then or too garish later? Still others have praised the retrospective for refusing to take sides. Few can match the rawness of the early work or the multiplicity of the later work, they observe, echoing the diversity of gestural and geometric abstraction now. So what if one cannot have both at once?

The artist, too, has spoken of a break, almost like a conversion experience. He even locates it in his rediscovery of Caravaggio—who broke through to the Baroque while painting Saint Paul on the road to Damascus. Maybe early work, like Stella's "Benjamin Moore" series derives from its materials, but materials alone are no longer enough. In a book based on his 1984 Charles Eliot Norton lectures at Harvard, he calls instead for Working Space. "What painting wants more than anything else is . . . space to grow with and expand into," he writes. "Painting does not want to be confined by boundaries of edge and surface."

Maybe, but the passive voice is telling, in an artist who has made a career of refusing evasion. The retrospective challenges one to locate the break. Works come in series, one after another, and each has its own way of shaking things up. Every so often, the show leaps back or ahead, with a painting from a different series. The pairs may even resemble one another in their logic and their determinants. As much as ever, Stella is asking what counts as painting while daring you to let him shove it in your face.

Reason in squalor

There is something very New York about "in your face," and he arrived in the city when the New York School was still in everyone's face. The early drips, stripes, sharp angles, and black squares are not so very far from Alfred Leslie, who was working his way out of Abstract Expressionism then, too. Stella came by way of prep school and Princeton, where he met Walter Darby Bannard, but this was painting without aristocratic reserve. He had his studio in Chinatown, and early titles like East Broadway and Astoria take their cues from the city. When he settles on blackness, like Franz Kline before him, a title proclaims The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, and that seems right as well. One cannot have the logic without getting one's hands dirty, too.

His art never surrenders its squalor. It bears the weight of cruelty and disaster, right down to the earthquake in Chile. Another black painting, Die Fahne Hoch! (or "the flag on high," from an anthem of the Nazi party) could hardly be more in your face, right down to its exclamation point. The allusion to mindless patriotism and manipulative displays is provocative as well, in an art scene so often dedicated to sincerity. Stella's first relief paintings, "Polish Villages," take their titles from the sites of destroyed synagogues. An early shaped canvas is a yellow star.

Yet he never gives up on reason either. "The flag on high" also alludes to the flag paintings of Jasper Johns. Stella even calls a mitered maze Jasper's Dilemma. Like Johns, he ditches representation in favor of the thing itself, only to find himself in constant dialogue with earlier works and with himself. And that adds another way of looking at Stella's break points and color in the 1960s. The more he pursues the logical foundations of painting, the more he finds himself in a new working space.

The Marriage of Reason and Squalor already redoubles its logic. It has a mirror design, like the marriage of two black paintings side by side. The logic of materials requires him to paint the stripes by hand, with breathing space for canvas and, at times, pencil between the stripes. Yet that very logic soon has him seeking other materials instead. Some striped paintings turn to copper or aluminum paint, and some look to notches or shaped canvas to determine the direction of the stripes. And then the "Irregular Polygons" oblige him to abandon stripes, much as regular polygons obliged Bernard Kirschenbaum to look for the spaces in-between.

The Marriage of Reason and Squalor already redoubles its logic. It has a mirror design, like the marriage of two black paintings side by side. The logic of materials requires him to paint the stripes by hand, with breathing space for canvas and, at times, pencil between the stripes. Yet that very logic soon has him seeking other materials instead. Some striped paintings turn to copper or aluminum paint, and some look to notches or shaped canvas to determine the direction of the stripes. And then the "Irregular Polygons" oblige him to abandon stripes, much as regular polygons obliged Bernard Kirschenbaum to look for the spaces in-between.

They do not go away without a fight. The last stripes, the "Protractors," have the broadest bands, the brightest colors, and the largest scale. Damascus Gate from 1970 occupies an entire wall—the back of the very entrance wall that holds Das Edbeden in Chile. Again one had better be looking for parallel inconsistencies and parallel logic. The series also introduces a new point of self-reference, in the artist's tools. It begins with protractors, represents them, and could serve as them as well.

The series marks a break in going beyond the artist's hand, but only so far as to the tools of his trade—and his tool kit keeps growing. The shapes in relief paintings from the 1970s allude to French curves, while the twisted grids in later work allude to computer-assisted design. Where early stretchers turn their wood on its side, calling attention to its thickness, later paintings invite one to look at the sides of honeycombed metal, where he keeps painting. The twisted grids also appear as literal support in smaller maquettes. Maybe the artist's materials still rule after all. They just rule an increasingly mad kingdom.

The Great White Whale

The interlocking wood slats of the "Polish Villages" fan out gently, and one of the strongest remains unpainted. Soon enough, though, Stella turns to aluminum for his "Exotic Birds," and painting does more than take flight. It threatens to crash to the ground. For the first time, he paints with no reference to the shape of the support. His brush, spray, lacquer, and oil stick point only to the vocabulary of painting. Paintings like Gobba, from 1985, also introduce illusion, with the appearance of cylinders and cones.

And then, with the millennium, Stella once again ditches illusion in favor of the thing itself. Some paintings poise the fluid shapes of aluminum against steel tubes, like tripods coming out of the wall. Others fragment into metal shards and coils. They pretty much abandon logic at last, not entirely to their credit. The curator, Michael Auping, does well to minimize them, in favor of work with greater mass and volume. They accurately reflect, though, a shift in allusion—from looming disaster to lifelong struggle.

The shift appears in allusions to Romanticism. The crusty freestanding work is The Raft of the Medusa, after the painting by Théodore Géricault. "Das edbeden in Chile" quotes a German Romantic poet, Heinrich von Kleist, while a series from the late 1980s compares its aluminum surfaces to Moby Dick. Feminists have every reason to shake their heads—although a woman, Dorothy Canning Miller, selected him for "Sixteen Americans" at MoMA in 1959, and Alan Solomon for the 1964 Venice Biennale, and no artist comes closer to his chaotic shapes than Elizabeth Murray and Murray drawings. Still, not every struggle is heroic, and (to return to the mitered maze on the entry wall and its title) pratfalls are blunders. The great white male is mocking himself as the Great White Whale.

With its first major loan exhibition in the Meatpacking District, the Whitney faces a serious reality check for both its subject and the museum, and it does well on both counts. With a huge display of its permanent collection, a survey of Archibald Motley, and now this, it sends a message that it is committed to both diversity and tradition. And with a large retrospective on a single floor, the Renzo Piano architecture aces its first real test. Two sculptures, Black Star and Wooden Star, again a contrast of materials, also appear outside on the terrace. Stella had asked the Whitney for a show of solely recent work, and Adam Weinberg had to press him for more. Guess who won.

Weinberg, the Whitney's director, was dead on. Any gallery can hype the latest, like too many a museum "midcareer retrospective," and a great museum can do more. It has the resources to assemble a career—and a public commitment to narrate it as history. Stella's former Chelsea gallery lends its support as well the same fall. It, too, takes Stella through the years between those notorious "Black Paintings" and his late, often mannered fragmentation of the art object. Both shows discard the chronological arrangement of "Stella Since 1970," the landmark 1978 exhibition at MoMA, with its insistence on the unfolding logic of late modern art, as a kind of "science marches on."

Instead, they present the unity and variety of Stella's logic—with stripes, shaped canvas, metal tubes, and gigantic French curves alike as the architecture of color and the shape of things to come. There is no going back to the exhilaration of the "Black Paintings," with their influence on Minimalism, and in that sense there truly has been a break. Yet an art of questioning is still very much "in your face." The Whiteness of the Whale, from 1987, has no white at all. Maybe Stella's pursuit of painting's essence is as doomed as Ahab's pursuit, but he cannot stop himself. He is still asking whether it means anything, and he refuses to take yes for an answer.

Frank Stella ran at The Whitney of American Art through February 7, 2016, and at Paul Kasmin through October 10, 2015. Related reviews take up Stella in the 1960s and Stella's late paintings.