When Great Artists Borrow

John Haberin New York City

Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends

Robert Rauschenberg did not traffic in stolen property. Yet few have taken more risks in the name of art.

Everything may seem, barely, above board. Rauschenberg bought the toilet paper of his black paintings over the counter, and he rescued the soiled bedding of a shocking combine painting from the trash. Yet no one else can bring art so close to criminal conduct. And no work comes as close to a defacement of private and public property as his Erased de Kooning Drawing of 1953.

At least critics at the time thought so, but Willem de Kooning handed over a drawing knowing full well what would become of it. The older artist did not just go along with the game either. He got into it, selecting a composition with several figures that he knew would be difficult to erase.  In Rauschenberg's recollections, the number of erasers and the time it took kept growing with each retelling. Jasper Johns got into the game, too, supplying a frame and a label as integral parts of the work. If Rauschenberg committed vandalism, he had partners in crime.

In Rauschenberg's recollections, the number of erasers and the time it took kept growing with each retelling. Jasper Johns got into the game, too, supplying a frame and a label as integral parts of the work. If Rauschenberg committed vandalism, he had partners in crime.

The Museum of Modern Art takes collaboration as its theme, for a mammoth retrospective. It places the artist "Among Friends," including work with and by others along with the breadth of his career. It argues for his art as interdisciplinary, egalitarian, and open. It helps in understanding his frequent shifts in substance, style, media, and materials, as he kept up with friends and influenced them in turn. People like to say that good artists borrow, but great artists steal. MoMA sees Rauschenberg as not just borrowing, but repaying the loan with interest.

Student and teacher

The line about stealing comes in several versions (sometimes with copy in place of borrow), and Pablo Picasso may or may not have coined it. That confusion only adds to its assault on the "originality of the avant-garde"—and who more than Robert Rauschenberg led the assault? Robert Hughes long blamed Andy Warhol for ruining modern art, like the Huns descending on classical civilization, but Rauschenberg was the consummate vandal. He took the readymade from Dada, with all its refusal of art, and turned it into appropriation, with all its refusal of art apart from the world. It made him a founder of Pop Art and a leading influence on the turn away from painting with the "Pictures generation" after 1980. It allowed him to work, as he liked to say, in the gap between art and life.

For MoMA, it also makes him a natural collaborator. Right out front stand classics of Pop Art from the museum's collection, like Warhol's Marilyn and a soft telephone by Claes Oldenburg. Already Rauschenberg is among friends. The exhibition proper then opens in 1950 with ghostly blue photograms by him and his wife at the time, Susan Weil. They took turns posing and photographing the other. For one, she adjusted the light sources so that he appears twice in collaboration, as if holding his own hands.

The interchange of ideas and materials takes at least half a dozen forms over time, roughly in parallel to his growth as an artist and teacher to such as Al Taylor. Naturally they begin with him as a student. Weil introduced him to Black Mountain College in North Carolina—and its éminence grise, Josef Albers. From his years at the Bauhaus, Albers brought a trust in color and materials, and they guided Rauschenberg in paint. If anyone still questions whether his early black, white, and red paintings gloried in or subverted Abstract Expressionism and then Minimalism, consider both. Paintings in soaked toilet paper hang next to paintings in gold leaf of the same dimensions, daring one to ask which to take seriously.

At Black Mountain, Rauschenberg produced more photography than painting, under the influence of Helen Larsen Archer. Like Archer, he shows spare interiors in hauntingly asymmetric compositions flooded from behind with light. Call them fine art, a lived environment, or the gap between art and life. From this point on, he is no longer a student, but he is always still learning. A second form of collaboration resembles an artist's with his workshop. With Rauschenberg, though, the roles blend together.

They do with the white paintings, which he asked Brice Marden and others to execute on his behalf. He did so to erase the artist's hand, just as with the erased de Kooning. Yet he was not above adding the marks of his hand in pencil, bringing him closer to Cy Twombly. And a third kind of collaboration is that of friends working side by side, pushing each other forward, like Georges Braque and Picasso before them. A calligraphic painting by Twombly hangs next to a monochrome by Rauschenberg, making it harder to dismiss Twombly's experimentation or Rauschenberg's casual gesture. As Jacques Derrida might say about the de Kooning drawing, their art still exists under erasure.

Rauschenberg met Twombly at the Art Students League on 57th Street, brought him along on a return to Black Mountain, and traveled with him to Rome and Casablanca. They collected scrap metal together, as the materials for sculpture, occult objects, or a travelogue. And then another friend and lover complicates things once more. Where Jasper Johns casts beer cans in painted bronze, Rauschenberg hangs a pocket watch over a tin can as art—or as marking time. A painting by one with a red background, Target with Four Faces from 1955, hangs next to a red painting by the other. It also uses Rauschenberg as the mold for its row of plaster casts, a reminder of their impersonal art and personal intimacy.

The dancer and the dance

A fourth form of collaboration puts the emphasis on the back and forth. Archer had invited Aaron Siskind to Black Mountain, where he shared his photography of scrap-ridden streets. Back in New York in 1953, Sari Dienes takes direct ink traces from a Soho sidewalk, while Robert Rauschenberg has John Cage drive a Model A Ford over twenty sheets of typewriter paper to leave its tread. Maybe Rauschenberg had the streets in mind, too, that year when he passed off boxes of dirt as paintings. Dienes also scavenged the taxidermy goat for Monogram, a combine painting—and it wears around its neck an automobile tire. Extended moments like this give a breakthrough a history.

A similar history opens with the red paintings, which Merce Cunningham asked him to adapt as a stage set for dancers in 1954, just one of collaborations with dance, including the costume designs in "New York: 1962–1964." They took his work fully into three dimensions, just when Alvin Ailey in dance was influencing a new generation of artists. Soon after, Rauschenberg asked to include friends with him in a gallery's annual group show, as was the custom. When the gallery denied them, he incorporated a copy after Jasper Johns in Short Circuit—along with bits and pieces from Weil and Stan VanDerBeek, an autograph from Judy Garland, a concert program from Cage, and hinged doors. By 1959, the wood had become a ladder running up the middle of a painting, leading into the chill of Winter Pool. By degrees, a flat surface had become space, collage, and a combine painting.

A fifth form of collaboration is of necessity. As the media became more interdisciplinary, sometimes he had to ask for help. He did with his turn to silkscreen in the 1960s, after having introduced transfers into thirty-four prints, one for each canto of Dante's Inferno. He visited Warhol, who in turn asked for photographs from Rauschenberg's childhood in Texas for another silkscreen. For him, though, silkscreens become something else again—not a mark of repetition or a reflection of pop culture, but a more complex record of their time. They run from JFK and the moon landing to Peter Paul Rubens, determined never to lose hope and never to forget.

Technical assistance came up again in 1966, when he asked Billy Klüver of Bell Labs for help with circuitry for sound art at the Lexington Avenue Armory, the site of the legendary Armory Show fifty years before. The immediate result was the formation of the Experiment in Art and Technology, or E.A.T., a league that grew to several thousand members, long before art and the Internet. A bit later the collaboration produced a Mud Bath—and another displaced memory of Texas. A white chemical used in oil production burbles up more or less violently in response to ambient sound. Maybe the ultimate result, though, was a permanent shift from painting to spectacle. With the growing loss of physical capacity, Rauschenberg relied more and more on photographs by others.

One last kind of collaboration runs throughout his career, work across the arts—and no art form appears more often than dance. The community at Black Mountain also included Cunningham, and Rauschenberg joined in the dance as well. Later he contributes sets, costumes, and choreography to Paul Taylor, who poses stiffly in a suit like a stand-in for the artist. Paintings and sculpture after road signs could pass for diagrams of dance steps. Musicians like Cage and David Tudor, too, joined in the living theater. MoMA ends with collaborations in art and dance over the course of seventeen years with Trisha Brown, the choreographer who also worked with Donald Judd and Nancy Graves.

The show itself is an exercise in set design, much like Tiona Nekkia McClodden with dance floors for Dance Black America. The curators, Leah Dickerman and the Tate Modern's Achim Borchardt-Hume with Emily Liebert and Jenny Harris, turn for help to Charles Atlas. The filmmaker, video artist, and lighting designer worked with Rauschenberg. Here he gets a room of his own, for a jungle of video monitors with clips from several of the show's participants. He leaves his traces, too, as the retrospective turns more and more into competing video clips and slide shows. What began in black and white leaves the blackness behind.

The collaborator in isolation

But why stop at six? One can speak of collaboration as simply the company of others, with an artist notorious for his sociability. When he came to New York, he found a studio among others on Fulton Street, and he just had to drop in on the Abstraction Expressionists at the Cedar Bar. When he met Morton Feldman, the composer, he just had to him to perform at an installation. One can speak of other forms of dialogue as well. It extends to myth and the past, as with the Divine Comedy, and into a wider world in the earliest and greatest silkscreens.

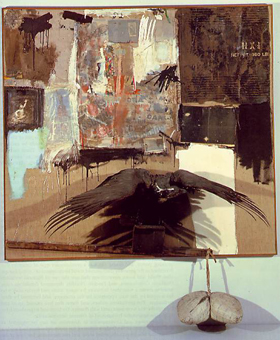

It extends abroad, as a trip to India in the 1970s exposes him to colored silk. Later he forms the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange, or ROCI, with glib posters and vague intentions. The dialogue extends to unspoken private matters as well. The eagle in Canyon, a combine painting from 1959, alludes to Ganymede, a youth sought by Zeus for his beauty—and to Rauschenberg's homoerotic longings. Or maybe the dialogue extends to the entirety of art in his lifetime. He exhibited his appropriations in a show with Duchamp's bottle rack and his interactive art with the self-destroying Homage to New York by Jean Tinguely.

The idea of collaboration brings real insights, but wait a minute. Its plenitude of meanings pushes it to the breaking point. In music and dance, each participant has an assigned role. In Rauschenberg's art, I am not so sure. Does he even need another show, after the Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim twenty years ago and a survey of the combine paintings at the Met in 2006? I was more cogent in reviews of both, and I hope that you will have time to read them.

The show risks defanging him at that. Collaboration sounds ever so reasonable and cuddly. Maybe great artists do steal, and none more than Rauschenberg. Apparently de Kooning felt the loss. He had agreed to help a fellow artist, but he resented seeing his name on the erasure in public. The soiled bedding may have belonged to Rauschenberg himself or to Dorothea Rockburne, who disliked seeing it bloodied with paint and attributed to someone else.

Even Rauschenberg had his difficulty collaborating. At the Cedar Bar, he found it hard to talk to the like of de Kooning. He might find this show just as overwhelming. It has more than two hundred and fifty works and ever so many artists. Collaboration means that each object has quite a history, and the wall labels insist on telling it. A few rest behind ropes, too far away for easy reading.

Still, the show is overwhelming for good reason, because so is that history and so is Rauschenberg. It may even overturn one version of him, along with its own theme. I had always written off the lightness of cardboard boxes from the 1960s and the seemingly endless late silkscreens to reliance on assistants, but maybe they represent a falling off in collaboration instead. Starting in 1962, he spent much of the year in Florida, to recover the "isolation needed for productivity." He began delegating more than collaborating. By his death in 2008, he could steal from no one but himself.

"Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 17, 2017. Related reviews look at a Rauschenberg retrospective and his combine paintings.