Modern Art and Anarchy

John Haberin New York City

Félix Fénéon and Paul Signac

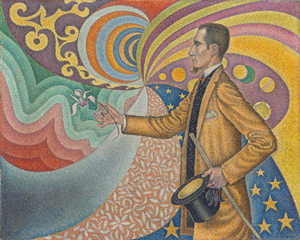

Paul Signac had few equals as an artist, but Félix Fénéon was something else again. For Signac he was nothing less than a magician.

Signac in fact painted him as one, in 1890—only he had pulled out of his hat not a rabbit, but Post-Impressionism. He even gave the movement its name. If Signac helped take art from Impressionism to Modernism, Fénéon did so as well, but as a writer, editor, and dealer. For him, the avant-garde was nothing less than a revolution, a blow for anarchy with humanity at stake. Does that sound downright quaint, all the more so with museums shuttered for Covid-19? MoMA hopes to recover its urgency.

On trial for conspiracy after anarchists bombed a Paris restaurant, Fénéon was confronted with the testimony of his landlord. Had he not consorted with awfully suspicious people? He could neither affirm nor deny it. They were, he duly explained, painters and poets. Besides, if painters and poets had become suspicious characters, they did so on his watch as a writer, editor, collector, and dealer. He could in fact take credit, along with credit for the very term Post-Impressionism and for early modern art.

Fénéon's reply matters because his wit and polish never deserted him—at least until, late in life, he suddenly withdrew from art. It may even have got him off in court. His reply matters, too, because quotes like this, in wall text, are part of the experience of seeing his show in person. So are exhibition catalogs for Henri Matisse, from a dealer who supported the artist to the extent of a retrospective with more than ninety works. So are exemplars from his collection of non-Western art long before others, and so above all are paintings. They cry out to be seen, after months in a lockdown.

The critic as magician

Paul Signac depicts quite an act. If it is in landscape rather than portrait mode (and cuts off the top of its subject's head at that), Félix Fénéon looks no less commanding. He merely commands a wider stage. Unsmiling and in profile, he holds out his right arm and cocks the other at his elbow, with all the seriousness of art and the confidence of a star. He also dresses as one, in a dark vest and high collar—and with a dandy's pocket handkerchief and cane. The gilded inside of his magician's hat all but matches the yellow of his long jacket.

He has indeed plucked from it not a cute and cuddly circus animal but a new art. He holds out a single flower, its frail petals and slimmer stem finding their echoes in the pointed wisp of his beard. He has produced just as much the swirls and stars of color filling and flattening the painting as they fan out behind him, but this is no mere trickery. It is painting's future. Credit the artist, but Fénéon pushes his envelope as well. As usual, Signac employs the tiny dots of Pointillism, but he never again came so close to decorative art or abstraction.

A lengthy title pushes the envelope, too, Opus 217, Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones, and Tints. You may associate art of its time with silence, like that of Paul Cézanne and a still more imposing Pointillist, Georges Seurat. Yet Seurat had his own Circus Sideshow as a metaphor for his art, and Fénéon championed him as well. Signac was not often verbose either, but all Fénéon had was words. Félix Vallotton shows him at his desk as editor of La Revue Blanche, working well into the night. The green glass of a desk lamp and its artificial light supply the sole splashes of color.

Like any magician, he would have known that the appearance of magic is only an illusion, and modern art took special pleasure in piercing illusions. Within just a few years, abstract art was to dispense altogether with illusion, although Fénéon never quite went there, no more than Signac. Still, his commitment to painting rested on a commitment to bursting social conventions as well. As the show's subtitle has it, it is the story of "The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde." The French even rounded him up along with the usual suspects after an Italian anarchist assassinated the French president, Sadie Carnot, in 1894. He looks almost as magical if more brutal in a mug shot.

Anarchism may have you thinking more of Dada and anti-art than painting. What could be less political than Signac's portrait—or the hush of evening in his Channel at Gravelines? The show does include Funeral of the Anarchist Galli, by Carlo Carrà in 1911, and police suppressing workers in a woodcut by Vallotton. Still, if Fénéon styled himself an anarchist, it took Alfred Jarry in Paris to live the part. Fénéon was revolutionary only in promoting art. At times, the anarchist really does forge the avant-garde.

It may come as no coincidence that his mug shot, head on and in profile, echoes in the varied poses of three nudes by Seurat. She even ups the ante, as seen from the back, in profile, and face front. The twin goals come together as well in another painting by Signac, of men and women at play. It makes a striking pair with Seurat's Sunday in the park, while disrupting the greater artist's eternal stillness. As a prosy title has it, Au temps d'harmonie: l'age d'or n'est pas dans le passé, il est dans l'avenir. The golden age is in the future.

Two revolutions or one?

Fénéon was not yet thirty as Signac's magician. Born in 1861 in Italy and raised in Burgundy, he arrived in Paris as anything but a star. In a photo, that stovepipe hat is of a piece with the heavy dark coat of a struggling young writer. His father was a traveling salesman—maybe not a bad background for someone who promoted the achievements of others to a skeptical public. Still, the magazine folded soon enough. He supported himself for thirteen years as a clerk in the war office.

Museums have hoped to rescue dealers for art history before, like Edith Halpert in America. And Fénéon went on to direct one of the France's most storied galleries for almost twenty years, starting in 1906, but his greatest work was behind him. The show contains more than a hundred objects, but it shines in barely a dozen prints and drawings from the collection, almost all before 1900. He kept up with such modernists as Amedeo Modigliani, but his heart was in the last century. The show includes Henri Matisse, for a girl reading in dappled sunlight, but without the broad, flat colors of his most advanced work. It includes, too, a poster by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec for the Moulin Rouge, in all its fashionable decadence.

Museums have taken notice of critics before, like Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg as drivers of Abstract Expressionism. Fénéon kept up a regular column in the press even as a dealer, and MoMA makes examples available online. Still, Rosenberg's idea of "action painting" and Greenberg's formalism were at odds, and their story is all about competing certainties, whereas Fénéon juggles uncertainties with ease. He feels more relevant now, after Postmodernism and with art a troubled business. One remembers him not for his polemics, but for his artists. He could be the exemplar of uncertainty for art after Covid-19 and Covid New York.

He could be, too, when the museum closed the very week that his show opened to the public. For months, it had settle for a virtual exhibition, and I could see no more than you. Its "virtual views" pretty much boil down to eleven works—and they can only point to what gets lost in reproduction. The arc of a career is largely lost as well. Is art for the future after all or for the ages? Or must it speak most of all to the now?

The show will be most successful if it leaves you wondering. That very question gets at the birth of Modernism. It also gets at still another vital interest for Fénéon, who collected African and Oceanic art. The curators include Philippe Peltier of the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, who specializes in just that, along with MoMA's Starr Figura and Isabelle Cahn. They have selected a woman in a yellow sweater by Amedeo Modigliani from 1919. Her long neck, twisted pose, and blank expression derives at once from non-Western art, the sheer beauty of Modernism, and the anxieties of Europe after World War I.

Not even Fénéon could reconcile political and artist revolution. Part of him was always the anarchist toiling away in the war office, and then he withdrew. At his retirement at age sixty-three, he had nearly twenty years more to live, but he seems to have sought only idleness. As the most bitter irony in an anything but bitter soul, the champion of art and anarchy died in 1944, in a France still lost to fascism. It was to recover its greatness, but never again its central place in the avant-garde. I could only look forward to seeing in person what that brief virtual history leaves out.

Suspicious people

Those paintings sure cried out to me, on my first day back in a near-empty MoMA, and what a cry. Fénéon backed artists (and poets) from Pointillism to Futurism, but his "greatest passion" was for Georges Seurat. The first two walls run through more Pointillists than I knew existed. Later the show returns to Seurat, alone and on a smaller scale. One can see his precision coming to be not just in oil sketches, but also in Conté crayon, a medium as shadowy as charcoal and as demanding as metalpoint. It had to suit a figure as shadowy and demanding as Fénéon.

Seurat's command of light, it suggests, begins with a command of silence and shadow. In works side by side, he and Signac paint a shoreline at twilight. Signac's sky takes on an unnatural brightness, as if refusing to fade with the setting sun. Seurat's harbor scene has colors truer to life, ones that Claude Monet himself might have envied—but also a greater stillness, anchored by a dark lamppost and massive anchors. Each has his own magic, much as Signac painted Fénéon as a magician. That painting, it turns out, is smaller than I expected, but then in real life painters upstage the critic and magician.

That quote matters, too, because it challenges the show's thesis: Fénéon's dearest cause was anarchism, and it unites his taste and belief in art. He could not disavow it, not even to save his life, but painters came first. His landlord, he added, was not in a position to judge them. Was it their politics, their poverty, or their creativity that made them suspicious? The jury then found Fénéon innocent, but the jury today is still out.

It might seem hard to leap from Pointillism to Futurism. The first valued stillness, the second motion, and it flirted with fascism. Still, painting after painting in the first room praises workers—like sardine fishing by Albert Dubois, a man setting aside his work clothes to wash by Maximilien Luce, and a demolition worker by Signac. Creating a new world, like a new art, may mean demolishing the old one. Futurists depicted labor, too, and political action. Luigi Russolo painted The Revolt and Carlo Carrà that anarchist's funeral.

Then again, the industrial age could be deadening. When Signac paints gas tanks, they begin to loom only slowly over the foreground, where pants hang out to dry and the sand looks barren, in alternating patches of green and yellow. When he paints In the Time of Harmony, he insists that the future must be as composed as art, not anarchism. Then, too, Giacomo Balla paints a street light, like Seurat at dusk, and Gino Severini colors as broken as for Post-Impressionism. In between the movements, a poster on behalf of anarchism segues neatly into the poster for the Moulin Rouge. Maybe only Fénéon could have made these connections.

A revolt is a transgression, and a transgression requires transgressive actors. And the most striking transgressions here are sexual. When Pierre Bonnard paints a nude, her sprawl exposes her public hair and exceeds the bed. When Kees van Dongen paints a soprano, one could mistake her gaping mouth and garish reds and yellows for German Expressionism. van Dongen, though, is Parisian, and she is in drag. Fénéon cared about art and politics all the same, but with eyes wide open. If they may come into tension, that, too, part of art.

Félix Fénéon ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 2, 2021.