Poetry, Art, and Cooking Oil

John Haberin New York City

Engineer, Agitator, Constructor and Alfred Jarry

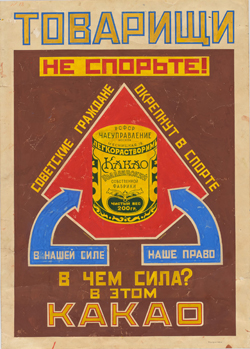

Six years into the Bolshevik revolution, one of the Soviet Union's leading artists collaborated with its greatest poet—on ads for cocoa, cigarettes, and cooking oil. And no, the ads did not rhyme.

They did, though, display an unmistakably cutting-edge style of prints. It appeared in the service of everything from posters to calling cards—and from politics to commercial advertising. It appeared, too, in the cause of revolution all across Europe. For some, the very idea of an artist seemed ever so yesterday, but art was no less vital to the future. It had become the work in "Engineer, Agitator, Constructor" at the Museum of Modern Art.  Subtitled "The Artist Reinvented," the crowded, messy show draws from a single private collector to pin down the pace of change.

Subtitled "The Artist Reinvented," the crowded, messy show draws from a single private collector to pin down the pace of change.

Speaking of the art of promotion, how about self-promotion? Long before Jeff Koons, Alfred Jarry took it as the impetus to modern art. Jarry invented his alter ego, Père Ubu, as a teenager, and it consumed much of his all too short life. It also allowed him his freedom—and his art. He barreled across Paris in and out of character, in and out of puppet shows, and on and off his beloved bicycle. People hardly knew whether to take delight or to take offense, but they took note.

One could almost forget that he found time for librettos to eleven operas, three volumes of autobiographical fiction, and Ubu Roi, the play that opened to outrage in 1896. William Butler Yeats in the audience knew hardly a word of French, but he knew that he had seen something strange and new. He must have recognized at least the sound of its opening word, merdre, and wondered whether to take it seriously. He may have wondered, too, whether Jarry's claims to a science of pataphysics paralleled his own metaphysics and myth making or was just plain nonsense. Was it all, then, a mere an adolescent prank, or was it the future of art? For the Morgan Library, Jarry stood at the very center of an emerging avant-garde.

This art means business

To John Heartfield and George Grosz in Berlin Dada, "The title 'artist' is an insult"—but what then to call the creative spirit? The show's title is just the beginning of a litany that artists adopted. MoMA quotes them as claiming the mantles of publishers and brand managers, graphic designers and photomonteurs, workers and theorists. For Hanna Hõch, also in Berlin, it took putting "works together like fitters." For Gustav Klutsis, a Latvian active in Moscow, it took "an entirely new type of public person, a specialist in political and cultural work with the masses, a constructor who has mastered photography, who can build a composition using entirely new principles." But what principles?

Do not answer too soon. Dada, after all, was about tearing things down, leaving only anti-art. The Bauhaus was instead about starting again, with rules that anyone could follow—rules for design and architecture that Josef and Anni Albers, Mies van der Rohe, and László Moholy-Nagy later brought to America. Early Soviet art, in turn, was about soaring above the rules in abstract painting. On the one hand, they were defying popular expectations for art. On the other, they were proposing art for the masses, in the Bauhaus and in Bolshevism.

So which was it? You could almost throw up your hands, but hold on. The artists embraced the tensions. Within months of their ad for cocoa, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Vladimir Mayakovsky were urging Russians to the Polish front in the face of western invasions and civil war. (The ad itself backed Lenin's New Economic Policy, which brought a modicum of private enterprise.) If they were not above promoting tea and cigarettes, Marianne Brandt in Germany was happy to design a silvery teapot and ashtrays, one more elegant than the next.

The art of cooking oil had broader support as well. Bart van der Leck, a founding member of De Stijl along with Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, created a poster for just that, but you might have to think twice to catch its connection to either painting or commerce. His ten drafts center on a single figure, progressively disassembled. He traced its origins to stained glass, and Mondrian's artistry will never look the same once you see it. Also in the Netherlands, Jacob Jongert and Fré Cohen designed cardboard boxes for coffee, tea, and oil. They anticipate Andy Warhol with his clones of Brillo boxes, but they are the real thing.

Dada had its practical and political edge, too. The show has not a hint of its origins in Paris, with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. No bicycle wheels and snow shovels here masquerading as an end to art. In their place, Heartfield's The Hand Has Five Fingers celebrates callused fingers and their spread. The poster became an emblem of worker demands everywhere. A collage by Grosz then depicts Heartfield as a suspiciously militarist exemplar of the German middle class.

Design could replace fine art or broaden it. In her short life, Lyubov Popova in Russia created costumes and stage sets, while Kurt Schwitters in Hannover contributed programs for a municipal opera house. Ladislav Sutnar made theater signs in Bohemia and Solomon Telingater posters for a traveling company of the Red Army Theater. Schwitters designed stationery, and what began for Max Burchartz as his calling card became letterheads and invoices for others. Henryk Berlew posed for an auto showroom in Warsaw as himself a salesman. These artists meant business.

Slashing diagonals and block letters

For all their differences, then, they had a shared sensibility. It is a contemporary one at that, now that postmodern distrust of art and capitalism has largely given way to a mutual embrace of art and design or art and fashion. Schwitters never tired to explaining that he named his avant-garde magazine, MERZ, for the second syllable of commerce in German. Herbert Bayer, MoMA explains, made the discovery that a winning "design for electric lighting could itself sell electricity." It is a collector's sensibility as well, that of Merrill C. Berman. Roughly two-thirds of the work has now entered MoMA's permanent collection as his gift.

Of course, it is a shared visual sensibility, too, and in that a more dated one. You can catch again and again its slashing diagonals and block letters in a harsh red and black. Despite three hundred works from between world wars, the show passes a little too quickly. So many names can blend together. It can also become chaotic, with scant regard for chronology. You may be well into it before you realize just how bracing and revisionist it is.

That comes right off in presenting such unfamiliar artists as Klutsis in Russia on a par with El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, and Popova. It comes, too, in the collision of Russian Constructivism, the Bauhaus, and Dada. Willi Baumeister all but obliterates his 1927 poster for housing with a terrifying red X. It may come most of all, though, in ditching a familiar story about them all. Think of Dada as a brief gesture of nihilism before Surrealism—and Suprematism as a brief gesture of pure painting before Stalin crushed it for good? Here the lessons endured for more than twenty years.

That comes right off in presenting such unfamiliar artists as Klutsis in Russia on a par with El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, and Popova. It comes, too, in the collision of Russian Constructivism, the Bauhaus, and Dada. Willi Baumeister all but obliterates his 1927 poster for housing with a terrifying red X. It may come most of all, though, in ditching a familiar story about them all. Think of Dada as a brief gesture of nihilism before Surrealism—and Suprematism as a brief gesture of pure painting before Stalin crushed it for good? Here the lessons endured for more than twenty years.

The curators, Jodi Hauptman and Adrian Sudhalter with Jane Cavalier, see Russian art still in support of "five-year plans" and the regime under Stalin. (Students of Futurism in Italy will already know of its weakness for fascism.) They see figurative art as not an end to creativity, but an acceleration of its fighting spirit. It also brought new threats and opportunities for women, including Cohen, a Jew who died of her own hand facing the Holocaust. An entire wall for posters by Valentina Kulagina, Natalia Pinus, Elena Semenova, Varvara Stepanova, and others shows women as creative artists and, in their subjects, muscular workers. Lydia Naumova used denser compositions to crunch the data.

The show can count on sheer volume—enough for an extended focus on Popova, on Schwitters in his experiments with typefaces, or on Max Bill with stronger colors. It can also count on the museum's larger collection for a few strategic additions. A sculpture by Moholy-Nagy like a loose, springy coil translates easily into a cover design. (Along with MERZ, other magazines included Ma in Budapest and Blok in Warsaw.) While posters dominate, canvas by Mondrian and Malevich slips in, too, with every indication of that shared sensibility. Maybe some artists resented the label, but maybe they did not abandon the studio and easel painting after all.

Or was it only a dream? To the end, Heartfield was protesting Hitler, and he lost. Film by Ella Bergmann-Michel remembers the last free election in Weimar Germany, in 1932, as a torrent of political posters and electric signage, but now they are museum pieces. That poster by Baumeister all but cries out in confusion and pain with the words Wie Wohnen? "How should we live?" It must have already felt perilously late to ask.

Modernism's guerilla theater

Alfred Jarry was born in 1873, the year that Arthur Rimbaud finished A Season in Hell, and died in 1907, the year that Pablo Picasso unveiled Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the brothel scene that dares you to turn away. It might just as well have placed him between two more blatant shocks. Edouard Manet and others exhibited their rejected art as the Salon des Refusés in 1863, while The Rite of Spring, with music by Igor Stravinsky and choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky, caused a riot in 1913. Jarry, then, could claim neither the first nor the last great scandal in modern art, but no one more consciously sought one. With that opening word (close to merde, the French for shit), he rubbed the audience's nose in excrement, at least linguistically. To add to its crudity, he could not even be bothered to spell it correctly.

He had just as cavalier an attitude to great art. The play shifts Macbeth to Poland, only the usurper and his wife get away with murder—fleeing to (you guessed it) Paris. (The extra R in merdre makes it sound like murder in English.) Scandals in art these days are not what they used to be, and any number of artists later illustrated Ubu Roi and its sequels, including Joan Miró, Max Ernst, David Hockney, and William Kentridge. Hans Bellmer did so with sexually charged puppets that Jarry would surely have embraced. Dora Maar, too often remembered as only Picasso's lover, may have them all beat with a photo of King Ubu as an armadillo, well before Cubism in photography spread to Brazil.

Did Jarry change the course of art? He started drawing as a child and illustrated the program notes for Ubu Roi. His broad, harsh line has the feel of child's play or outsider art. Woodcuts, too, appealed to him because they served as a popular art form in the Middle Ages. He shares that fascination with the mystical Symbolism of his time as well—extending to Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Hilma af Klint, and Frederic Leighton. The exhibition finds a similar line in Edvard Munch.

All well and good, but Jarry might have had a tough time with the religious imagery of Bonnard's Annunciation. He has little of Munch's anxiety either, not when he could be cruising the streets. Besides, mostly the influence runs the other way, from artists to Jarry. He admired an allegory of war by Henri Rousseau in 1894, with a little girl on a wild ride over naked corpses as crows draw blood. He became fast friends with Paul Gauguin. If Gauguin had taken up children's books, they would have looked like lithographs by Jarry.

The curator, Sheelagh Bevan, reaches hard for signs of Jarry's influence. Picasso admired him, but it is hard to see what difference that made. He found another friend in Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet who celebrated Cubism, but he did not live to see it. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec depicted a bicycle race, but for once Jarry was not a rider. Still, he was fascinated by the confluence of art and words, right down to typography. His night scene after Gustave Doré is as sinister as the original and then some.

His greatest legacy, though, was his defiance, including life itself as an extended work of performance art. You may read that he anticipated Dada, Surrealism, and the Theater of the Absurd, but he could never have sat still long enough to wait for Godot. He comes closer to the guerilla theater and street art of the 1960s, and did I mention Jeff Koons? He died at thirty-four of tuberculosis, as if he could not trust anyone over thirty. A moralist would say that he brought it on with drinking and drugs, but you know what he would have said of moralists. It would have begun with the letter M.

"Engineer, Agitator, Constructor" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through April 10, 2021, Alfred Jarry at The Morgan Library through August 1, 2020.