The Promise of Modern Photography

John Haberin New York City

Fotoclubismo in Brazil and Richard Benson

More than fifty years ago, a movement in Brazil had a thorough grounding in modern art and design. It featured outsiders to photography, with due emphasis on women, but photography in Europe never came close to its eclecticism and modernity. As a postscript, a lone photographer in one of America's most established academic programs found another side to the medium's Modernism as well. First, though, to Brazil.

"Fotoclubismo Brazil" introduces a collective, but it opens on the theme of solitude. Solitude can be lonely or revivifying, a forced isolation or the choice of a pioneer, and the Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (or FCCB) embraced them all. It took its name from colonial fortune hunters in São Paulo, overlooking a history of slavery and Portuguese control. The group's pioneer, Geraldo de Barros, snapped his self-portrait with sunlight as the mask of Zorro over his eyes. Yet one can feel the loneliness in an empty chair or a little girl facing an ill-defined landscape and an uncertain future.  Never mind that Ivo Ferreira da Silva calls his photo of a chair Confidential—and Dulce Carneiro saw in that girl the promise of Tomorrow.

Never mind that Ivo Ferreira da Silva calls his photo of a chair Confidential—and Dulce Carneiro saw in that girl the promise of Tomorrow.

Or rather do mind, a lot, for this is modernist photography, and the collective believed in its promise. That promise brought urban professionals together on weekends, as sophisticated amateurs. It was a political promise as well. FCCB was founded in 1939, and MoMA sets a thrilling survey in the floor for art before World War II, with work almost entirely from the collection. Yet it took off for real in 1946, when de Barros signed on and the club's magazine, Boletim Foto-Cine, began. That was the first year of a republic, and the group died in 1964 along with the republic, as a dictator seized control of Brazil.

When a photographer is the son of a stonecutter and the uncle of a carver, expect a belief in industry and in craft. Richard Benson might hardly distinguish one from another, and it makes for a challenging view of photography and modern America. A visitor to his retrospective could easily pick out two distinct bodies of work and wonder at the contradictions between them, but just how different are they? As the Philadelphia Museum of Art has it, "The World Is Smarter than You Are," and no doubt so is he. He could outsmart even himself.

A collective solitude

Modernity can be isolating, too, most of all when one is one among many, like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. But again never mind, for Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante delighted in the signs of modernity, like telephone wires for Thomaz Farkas or a manhole cover for Marcel Giró. These days one expects Brazilian art and Brazilian artists to reflect a uniquely Latin American art and indigenous history—like Rivane Neuenschwander, Roberto Burle Marx, Luiz Zerbini, Lygia Clark, or Grupo Frente. This club knew only modern art as an ongoing experiment. Its clean esthetic and urban subject matter recall Margaret Bourke-White and, before her, Henri Cartier-Bresson. When Alzira Helena Teixeira captures the light through a curved overhead window, one might be in rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum with Frank Lloyd Wright.

Above all, FCCB's members had each other, in a show of sixty works—following up on MoMA's rehanging in its 2020 "fall reveal" (although already gone with the 2021 "fall reveal"). A photo poses a good thirty in its cast, clearly enjoying the company. They traveled together, and the photo has them stepping off a plane. They kept a scorecard on each other, and they worked side by side. Ademar Manarini photographs a man from behind, leaning against a plain white wall as he faces the patterned windows of a housing complex. With Eduardo Salvatore, the club's president, that complex and its grid of windows then take on a life of their own.

They had their common subjects, like architecture and utility poles. For Giró the Ministry of Education is a white trapezoid, as a backdrop for the wires. It is a short step from white roofs for de Barros to angled walls for José Yalenti or apartment blocks for German Lorca. It is a short step, too, from sand for Yalenti to rushing water for Farkas or raindrops on broken glass for Maria Helena Valente da Cruz. They loved blurred or broken silhouettes, like a busy airport for Lorca or an umbrella in the rain for Giró. With a concrete spiral, Gertrudes Altschul had her own foretaste of the Guggenheim still to come.

They had common techniques, like close-ups and overheads that push ordinary subjects to the verge of abstraction. Tires for Altschul look like monumental sculpture. They ran to back-lit subjects, like people in a park on Sunday for Barbara Mors. They experimented with photograms, solarization, and prints as negatives. When de Barros showed the way, it looked strange, and they drew back, but not for long. They photographed abstract painting, and the show includes a geometric abstraction by María Freire in Uruguay—but Freire had learned from them.

Just as innovative, they had women photographers, like Dulce Carneiro or the women in "Our Selves" at MoMA, starting when Altschul, already in her fifties, walked right in. She is one of just three artists with a section to herself, amid an arrangement by theme. Along with solitude, that includes sections for texture and forms, daily life, experiment, and simplicity, but these went together. White roofs for de Barros had to be corrugated, because texture and form were elements of modern life. Many a work could just as well fall in another section. Altschul may have a place to herself, but with a photo called Lines and Tones.

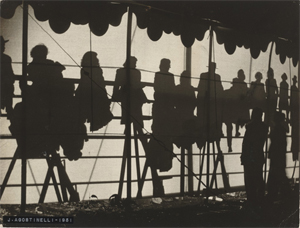

FCCB never gave up its status as weekend warriors. The curator, Sarah Hermanson Meister with Dana Ostrander, speaks of its work as carnival or familial—and Julio Agostinelli did photograph a circus, in (sure enough) broken silhouettes. Still, this carnival or family prefers solitude to people, for a proper Modernism and a portrait of modernity. The rare recognizable person stands out. Lorca photographs a terribly proper man reading, with a woman beside and behind him like a caretaker. The movement itself was having way too much fun to take care.

Engineering photography

As for Richard Benson, sharing a hall with Emma Amos, start with his changing subjects. They took him everywhere—from the Brooklyn Bridge in hazy sunlight to the underside of a bridge in Memphis, from row houses to the riches of Rome, and from apples laid out across a trellis to a Scottish engine that might have been long since left to its own devices. Who is to say which is more beautiful or a greater feat of engineering? But then Benson sees a Ferris wheel in New Jersey as engineering, too. He also prefers the long span of a bridge to a close-up that might bring it closer to Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante and abstraction.

He approached photography with a sense of beauty and the mind of an engineer as well. You may identify the medium with the camera's lens and the perfect eye, and self-portraits in a recent show of women in photography at the Met featured both. Benson looked instead to the darkroom for all that it could yield.  In an interview, he called himself the finest printer alive, at once boasting and accepting his limits. Born in 1943, he took up platinum prints for its subtlety and crispness. What else could give such weight to an engine and preserve its hard edges while bathing them in sunlight? When he took up color, he found the same contrasting perfections in a small boat in Newfoundland, its interior a bright green, and the light off distant clouds, rocks, and sea.

In an interview, he called himself the finest printer alive, at once boasting and accepting his limits. Born in 1943, he took up platinum prints for its subtlety and crispness. What else could give such weight to an engine and preserve its hard edges while bathing them in sunlight? When he took up color, he found the same contrasting perfections in a small boat in Newfoundland, its interior a bright green, and the light off distant clouds, rocks, and sea.

There, too, he leaves open whether his subject is commerce or pleasure, and again they are inseparable from his own industry and craft. William Eggleston or Stephen Shore might have let that green overpower the picture. He would rather put it in its place while etching it in memory. He brought that skill to others as well, with new prints of past work. The museum has display cases for prints after Robert Frank and the face of Abraham Lincoln, but his theme extends to Irving Penn, Lee Friedlander, and Helen Levitt as well. He took on the archives of Gilman Paper Company in 1985.

Now natural for him to devote his most massive project to a paper company. It also became bound books, because prints for Benson are means to education. How natural, too, then for the former Brown dropout to serve as dean of Yale School of Art—and to publish a history of photographic printing. Still, he pursued its potential in the present. He went from traditional prints to offset printing to digital, taking himself more and more out of the picture, and he tried his hand at digital overprinting as well. The pursuit of perfection has its contradictions after all.

Not that Benson distances himself from mere appearances, like Postmodernism and the "Picture generation." He is just not interested in politics or trickery. Still, he recognizes his distance from his subject. Late work in color finds him face to face with fences and siding. He is crossing the continent much like Friedlander by car or Frank in The Americans, but Americans are all but absent. When an American flag hangs from someone's home, it seems to exclude others as well.

Early work in black and white includes portraits, where he lets his guard down and shows his love. He shoots his wife in bed and standing, Young, Skinny, and Pissed Off. A woman in Puerto Rico cannot quite fill her bed, and (by the way) those apples are For John. Yet he reprints Barbara standing after many years, and the contrasts and contradictions vanish the more one looks. Benson is still the guy who built his own clocks and engines, right up to his death in 2017. He is still at once tourist and professional, still hard at work on the work of others.

"Fotoclubismo" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through September 26, 2021, Richard Benson at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through January 23, 2022.