Shaken or Stirred?

John Haberin New York City

MoMA's 2020 Fall Reveal

Gerhard Richter and Carrie Mae Weems

Not even Covid-19 could slow the pace of change for long, not at New York's Museum of Modern Art. But is that a good thing?

As a matter of fact, yes, even from an institution that long neglected its own and modern art's past. Barely a year after a massive expansion, it has rehung a full third of its galleries for the permanent collection, as its 2020 "fall reveal." If that has you scared, I understand. A textbook view of art history can sure stand some shaking up, and it has received one many times over—and not only at MoMA.  Just how far, though, can it go before even the collection looks more like a temporary exhibition? Can I still take a deep breath in front of Cubism or epic abstraction, and can I still have Starry Night?

Just how far, though, can it go before even the collection looks more like a temporary exhibition? Can I still take a deep breath in front of Cubism or epic abstraction, and can I still have Starry Night?

In practice, though, MoMA's "fall reveal" is not so much shaking as stirring, and the results are stirring, too. They include full rooms for major series by Gerhard Richter and Carrie Mae Weems, but art, like god, is in the details. The reveal reveals most with changes that most visitors will never even notice. It puts on hold some hard questions, such as how to deal with a block-long lobby, still all but empty. But leave that till the next reveal. After months of closed doors and revenue shortfalls, maybe the best news is that there an institution worth changing.

The Big Reveal

MoMA's 2019 expansion, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (in collaboration with Gensler), came as a wake-up call. There is no getting around around that its 2004 renovation was a disaster. It privileged blockbusters and pop-culture celebrities over the collection that defined not just the museum itself, but modern and contemporary art. It had also privileged architecture better suited to an airport terminal over a decent space for looking. Now it has three full floors for the collection, including one for art since 1970 alone. If that were not enough, it has promised to display still more of its holdings by rotating works on and off the walls every six months, and on that it has already delivered.

Otherwise, well, scratch that. Six months after its October 2019 opening, it was under lockdown, and even now you might think that a bomb scare had cleared the premises. When it reopened at last in late summer, I could have Vincent van Gogh and Starry Night to myself, like van Gogh in Saint-Rémy before me, if I waited a minute or two. Just days before Thanksgiving, ordinarily the start of peak tourist season, I need no longer wait. I had the whole room to myself, for the turn of the last century and the origins of modern art. The city told people to stay home, and they did. It took me back to my first getting to know art, before big money and big crowds—but at a cost, for time travel is never less than spooky.

Not that new architecture can solve everything anyway. It still obliges an artist (still, like a year ago, Haegue Yang) to take on its ridiculous atrium, with Amanda Williams due in 2021. Still, the collection is once again the museum's showpiece, even with a monster show of Donald Judd upstairs—plus a look back at an entrepreneur of modern art, Félix Fénéon. And that serves at least two purposes. It revisits the time line that the museum itself created, while stirring things up in the interests of Postmodernism and diversity. It boasts of both when it speaks not of a rehanging but a reveal.

But what does the Big Reveal reveal? Changes to twenty of sixty rooms sure sound like a lot, but the surprise comes in how much the Modern already accomplished in 2019. Enough is unchanged that it would take a perfect memory to say just what. Rooms for Claude Monet and Henri Matisse still show their breadth, with a show of Matisse's Red Studio coming soon, and Alberto Giacometti with Hands Holding the Void still dares one to enter the dark imagination of Surrealism and Pablo Picasso behind him. Constantin Brancusi still looks left out in a corridor by mistake, but the account of Abstract Expressionism looks more focused. You might have hoped or feared that any and all would now be gone, but no.

Eyebrow raisers from 2019 are still there as well, as revealing as then. The collection's second room still turns from Paul Cézanne and Post-Impressionism to early movies—a real boon for Garrett Bradley, who draws on a 1914 film featuring African Americans for her video installation downstairs. Jacob Lawrence still displays the entirety of his Migration Series. Joan Jonas still has a room for film as performance, self-revelation, and cryptic symbol system—just past four other women video artists. There are not all that many pairings of old and new, for all the hype, but Faith Ringgold still challenges Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. They do not so much discard Modernism as ask what was at stake all along.

Much else amounts less to fresh selections than to a fresh context, although modern photography in Brazil is coming soon. A room for Marcel Duchamp and Dada now stresses the role of chance mechanisms, enhanced by the Japanese art of Gutai, and a rehanging of Stuart Davis and prewar American art now stresses the role of New York City. Ripped off their walls, architectural elements by Louis Sullivan and others point to modern design as caught between structural clarity and decoration. The floor for contemporary art now looks less like sops to the market for painting and "girls just want to have fun." Instead, small works by a woman, Cady Nolan, hang near an African American, David Hammons, as twin challenges to American complacency. Hammons composed his circular array from liquor bottles resting on rubble, like cruel love among the ruins.

So what happened?

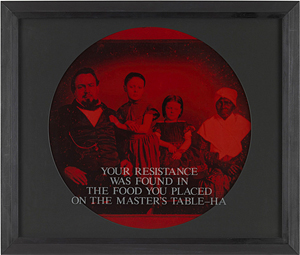

If the Big Reveal reveals anything at all to most visitors, it will be works in series by Gerhard Richter and Carrie Mae Weems, each with a room to itself. Richter's October 18, 1977 shows a skill and intensity that his retrospective at the Met Breuer not so very long ago left out. Named for the day that three members of the Red Army Faction, popularly known as the Baader-Meinhof gang, died in a German prison, it shows them in life and in death. Weems has a hundred fifty years of African Americans as seen first through white eyes and then through hers. Her title says it all: From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried.

But has it brought her to an outcry or to tears? Each series sticks to the facts, and each seems to represent a personal response. And each asks what either objectivity or the personal might take. Richter, working in 1988, sure boasts of brute fact—with his title, his photorealism, and the newspaper photos from which he worked. People often describe the series as mysterious, but much of the mystery lies in its immediacy. Subjects on the eve of death look ever so young and alive, and a dead man on his back looks inescapably dead. The moisture on their lips conveys the moment between life and death.

Richter uses a blurred focus to question the very idea of photorealism, just as the impersonal technique of his abstract paintings questions the possibility of formalism or expression alike. The blur also enhances the horror and appeal of his subjects, by immersing them in shadow and light. They seem all the more immediate by threatening to slip away. It enhances the allure of a radical terrorist group and of death itself, but their allure become a fact before he began and had already begun to fade. Richter calls the media phenomenon into question, but only up to a point. He questions, too, the temptations of his art.

Richter uses a blurred focus to question the very idea of photorealism, just as the impersonal technique of his abstract paintings questions the possibility of formalism or expression alike. The blur also enhances the horror and appeal of his subjects, by immersing them in shadow and light. They seem all the more immediate by threatening to slip away. It enhances the allure of a radical terrorist group and of death itself, but their allure become a fact before he began and had already begun to fade. Richter calls the media phenomenon into question, but only up to a point. He questions, too, the temptations of his art.

Weems starts with every conceivable token of objectivity. She, too, bases her series on photographs, meant as scientific studies of slaves in the nineteenth century. Louis Agassiz at Harvard sought the supposed essence of African Americans, since before Darwin everything in anthropology and biology was about essences. He asked what made them different and, in his eyes, inferior. And Weems only enhances the appearance of objectivity, submitting photos to a uniform size and blood-red tint. She crops them all in a circle, like specimens under a microscope lens.

Of course, she is imposing her perspective and enhancing their appeal as well, like Richter with a blur. Working in 1995 and 1996, she further dignifies her subjects by beginning and ending with identical photos, larger and tinted blue, of a literal African queen—and with text in block capitals. It opens with what could well be Agassiz;s words, like A Negroid Type, before speaking to a later racism and, ultimately, to a cry for dignity and understanding. Your Resistance was Found in the Food You Placed on the Master's Table—Ha, but You Marched & Marched & Marched Some Laughed Long & Hard & Loud. She leaves it unclear, too, just when the words slide from one stage to the next.

Allow me to leave much else to past reviews of Carrie Mae Weems in her Guggenheim retrospective and two now of Gerhard Richter—the one at the Met Breuer prematurely closed by Covid-19, like a human life. She can seem too sure of herself, even as she breaks down in tears, but who knows what in life is certain? The photos slip into the present, like her own Kitchen Table Series, including one by Garry Winogrand of a black man walking with a white woman and holding a monkey. Was he racist, too, or bringing racism itself to light and to life? Agassiz himself opposed slavery, and some of slavery's greatest opponents believed in white superiority, almost certainly including Abraham Lincoln. Maybe the biggest reveal is how much of the curtain art refuses to peel away.

The 2020 "fall reveal" of the permanent collection at The Museum of Modern Art opened October 21.