Working Out Identity

John Haberin New York City

The Kamoinge Workshop and Taller Boricua

Is that Malcolm X? It has to be, from his lean, angled face alone to the uncanny focus in his eyes. Or is it only someone who shares his eyeglasses, hat, and dedication?

Regardless, he is not acting alone—and neither, it turns out, were African American photographers. The photo's title reads only Muslims, for its plural subject, and I could not tell you whether Malcolm by then had broken with the Nation of Islam. But then the photographer, Lewis Draper, was concerned less for an icon than for a people, and he was himself part of a movement. Founded in 1963, the Kamoinge Workshop headed right for the March on Washington, but it returned to New York determined to see the larger picture. Its members went their separate ways, across New York and to parts of Africa, but with a common style and purpose. At the Whitney, they are "Working Together."

That workshop was not the only game in town. It was not even the only one to start in a tumultuous decade by and for people of color. Could I not have heard of either one? A second show makes a point of challenging a white male like me all the more. Just over a decade of Taller Boricua, the Puerto Rican print workshop in New York, ends on a high note, with painting. It ends in particular with a co-founder, Marcos Dimas.

An enormous face without a single flesh tone looks positively seared into canvas. It might almost be a photogram, between its stained surface and the sharp reds and blues of a photographic negative. I cannot swear to its gender or even its race, and yet its challenge is unmistakable. It is not, though, a god, a goddess, a lover, or a revolutionary but rather a Paria, or pariah. For El Museo del Barrio, the workshop might be that crazy old uncle that becomes something of an outcast, too, because he cannot leave off speaking his mind. Sometimes, though, for all his faults, the crazy one is as close as one gets to the sane, honest person in the room.

Ordinary heroes

The 1960s had more than its share of ideals and movements. A workshop member and its only woman, Ming Smith, has appeared in a show on the theme of Black Power, as did another African American photographer, Dawoud Bey and his Birmingham Project. Taller Boricua has its concurrent show, and Magnum Photos, the photojournalist collective, was alive and well. The decade also had its grandstanders, but not here. If neither Kamoinge nor its cast rings a bell, you are not alone. I recognized only Smith, who has also appeared in a show of "Race, Myth, Art, and Justice."

The workshop took its name from the people of Kenya, for whom it means "acting together." Acting might imply political action—while working might imply the day-to-day business of making art or staying alive. Should Kamoinge stick to specifically black subjects, and what would that mean? Its inspiration may have come from Africa, but what lessons could it take home? From the start, black photographers like Kwame Brathwaite debated among themselves. But then a workshop implies working out ideas in public.

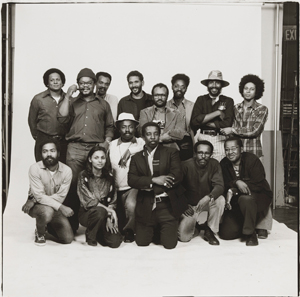

One thing was already clear, and it did not change with subsequent civil-rights action. This was about not leaders, although Anthony Barboza photographed Malcolm himself speaking out, but everyday heroes. Angela Davis appears, but on signs at a march. An ordinary man breaks into tears at the words of Martin Luther King. Barboza photographed each of the movement's fourteen members in close-up, for an accordion book, as well as in a casual but confident group. Still, when Beuford Smith allows himself a self-portrait, he loses himself in a waterfall.

They can sure get lost at the Whitney, which mixes them together rather than giving each one its own wall. It sticks to that formative decade, but it discards chronology, too. The movement, it seems to say, did not so much develop as survive to this day, as Kamoinge Inc. Some contributors stand out, like Draper with his overt politics—as with a girl in front of a wall spray-painted Cuba, like the next Che Guevara in training. Herb Robinson has more quiet lives and tonal variations, as with a seated man lost in shadow. But keeping them all straight takes some doing.

Kamoinge had its heroes all the same. It just happened to find them in the arts, especially music, and on the street. It photographed John Coltrane and Miles Davis, sidewalks and stoops, people together and alone. They can be most heroic in what for Bruce Davidson would be merely a place to play. A boy for Jimmie Mannas peeps out from a swim as if uncertain of the air, and a boy at a playground for Herman Howard takes a leap into the mist. A man for Adger Cowans seems on a long journey as he leaves his footprints in the snow.

It had its heroes in past photographers as well. It arose alongside the Black Arts Movement in England and America. In heading for Harlem and jazz, it was learning from Hugh Bell and Roy DeCarava, who had made the cover of Newsweek. (The curators, Sarah Eckhardt of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Whitney's Carrie Springer, throw in a copy.) With his group photos, Barboza looked to Gordon Parks. Members also cited as influences W. Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Dorothea Lange. Mostly, though, they seem satisfied to be lost in one another's company.

From politics to art

The show's layout may seem to downgrade them all, and the theme of everyday heroes may sound awfully sentimental. It may also sound like contemporary identity politics, from Mickalene Thomas to Kehinde Wiley, with their insistence on affirmation. Still, the group needs no apologies. The portraits may have star quality, like those of Grace Jones and Mahalia Jackson. More often, though, people appear not so much proud, but vulnerable. They gain in poignancy from coming together, like the gestures of field labor for Shawn Walker.

The Whitney groups photos by subject. If that furthers the impression of photographers that no one can tell apart, so be it. It also testifies to the workshop's range. After the marches come the trips to Africa, Jamaica, and Cuba. Street photography reaches past Harlem to Bed Stuy and the Lower East Side. Calvin Wilson prefers sunlight, while Robinson has his shadows. But portraits and photojournalism are only the beginning.

Kamoinge may not abandon politics, but it embraces art. For a collective founded on acting together, it almost leaves actors behind. When Herb Randall photographs tree climbers, they seem lost in the branches and the sun. More often still, they vanish entirely, in an approach to abstract photography unlike that of Wolfgang Tillmans or Yto Barrada. That can mean a salt pile for Al Fennar or, for Ray Francis, reflections in muddled water. As the decade ends, portraits return, but with fewer and fewer faces in close-ups. Even the predilection for jazz can mean an affection for the night.

Kamoinge may not abandon politics, but it embraces art. For a collective founded on acting together, it almost leaves actors behind. When Herb Randall photographs tree climbers, they seem lost in the branches and the sun. More often still, they vanish entirely, in an approach to abstract photography unlike that of Wolfgang Tillmans or Yto Barrada. That can mean a salt pile for Al Fennar or, for Ray Francis, reflections in muddled water. As the decade ends, portraits return, but with fewer and fewer faces in close-ups. Even the predilection for jazz can mean an affection for the night.

Does all this make sense? If a workshop is always a work in progress, where was it heading? Kamoinge may have had multiple themes, but also that shared purpose. The lay-out makes that clear, as the same photographers recur in different sections. It also makes clear how hard it is to set politics apart from a broader experience. Either one can be ambiguous.

Photographers return often to the American flag, but not simply to identify with their country or to reject it. Ming Smith shows a man standing in front of glass doors with flag visible behind them. Identity is at stake, but so are the borders that a black man cannot cross. Images of black culture can be ambiguous as well. Two women stake out Harlem's Amen Corner, a place for public speaking, but they are first and foremost sisters. When Daniel Dawson photographs African statuary, he could be searching for an African American identity or slamming the Met for exploiting it.

Much of their strength lies in the ambiguity. Even when Draper photographs a black man and white woman on the subway, he leaves uncertain whether to call them a couple or a confrontation. If there is a single common note, it lies in quietude, and if there is a single style, it lies in silhouettes, repetition, and reflections. One can see why Kamoinge's reputation needs reviving. Who wants political art that submerges its politics in shadow? Then again, maybe one should.

Dancing with revolution

As chief curator for El Museo del Barrio and its show's curator, Rodrigo Moura must know the kinship between a movement and a museum well. Founded barely a year apart, the institutions have a shared history extending to today. Taller Boricua (Spanish for Puerto Rican workshop), which opened just a few blocks north in 1969, had its second home on the site of the museum today, and the museum's co-founder, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, remained close. Marcos Dimas, still the workshop's executive director, sat on the museum's advisory board, and another former director, Fernando Salicrup became its director as well. Rafael Tufiño was a co-founder of both, and his daughter created a ceramic mural for the museum façade. Nitza Tufiño is another highlight of that final room for painting, with portraits set off-center amid rectangles of color—at once assertions of love and acknowledgments of isolation and marginalization.

Almost from the start, El Museo rubbed in that acknowledgment. A show of Puerto Rican art in 1973, in conjunction with the Met, excluded the workshop, which staged a boycott in return. Was it putting bruised egos ahead of the work at hand, when the museum was, arguably, furthering its very mission? Perhaps, but these were not just Puerto Ricans. They have little in common with the deep quiet of Zilia Sánchez, whose abstract art had a retrospective at El Museum last year, or the trickery of Rafael Ferrer, who exhibited there in 2010. Rather, they were Nuyorican, and New Yorkers know how to get in your face.

Taller Boricua dedicated itself to politics and populism. That is why it was a print shop. The style of its lithographs denotes both, too, with thick lines, unshaded areas, and jagged edges akin to woodcuts. Political artists like Sue Coe and Deborah Grant have turned to it as well. The elder Tufiño had a knack for elegance, as in a portrait of a dapper Don Pedro, but the very same series returns in no time to icons of protest. From posters to the pariah, this is an art of activism, with its principal subject the actors.

The rawness extends to forays in other media. Carlos Osorio embeds the word revolution in the colorful smears of near abstract painting. Jorge Soto Sánchez gives assemblage the shallow space of Joseph Cornell boxes, but also the brutality and blackness of discarded machine parts and charred, hacked wood. Still, a show of a print workshop necessarily leans to posters, which served as a tool for promoting the twin sides of a Nuyorican identity. One side was the island, with demands for revolution and independence. A Latina with child carries a gun.

The search for a Puerto Rican identity also motivates appeals to a native spiritualism—of Taino spirits and monsters. (The younger Tufiño also paints a Taino couple.) Over time, though, posters served more and more to promote a distinct culture in New York. Had hopes for independence faded, or had the vitality of East Harlem, with its night life and theaters, taken over of its own momentum? Either way, by the end of the 1970s, as the show comes to an end, Manny Vega has ditched overt politics for Dancing Under the Stars. For once, dancing with revolution looks like fun.

Raw edges can translate into crude art. Early prints, of unnamed faces and island hills, are hard to pin down. The most memorable posters can feel lifted from somewhere else. A sexier revolutionary graces a jacket for "Que Bonita Bandera," or "such a beautiful flag," and you will just have to look elsewhere to know how it became an anthem of revolution. The final room for fine-art media remains the highlight of a modest show. The crazy uncle at last gets to talk his mouth off, and a woman artist finally gets her due.

The Kamoinge Workshop ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through March 28, 2021, Taller Boricua at El Museo del Barrio through January 17.