The Future in Question

John Haberin New York City

Rem Koolhaas: Countryside, the Future

Marina Zurkow and Sarah Rothberg: Wet Logic

Rem Koolhaas has a question for you. Well, hundreds of them, lining the walls of the High Gallery at the base of the ramp at the Guggenheim.

Where did the cows go? And when did they leave? Is massage now a duty? Can we be natural and artificial at the same time? Can acronyms save the world? The two-story gallery has space for them all.

His answers are just as pressing, naive, and confusing. He urges them on you even before you enter the museum, with a tractor parked on the sidewalk, its wheels taller than you ever imagined, and a shed for growing who knows what.  Within the museum's rotunda, the floor bears any number of hazy cutout images—spinach, farm equipment, a cute Japanese robot, the covers of Silent Spring and The Origin of Species, creatures bred the old-fashioned way and genetically engineered. If they never quite add up, they are only a provocation and a summary of what lies ahead on the ramp. With "Countryside, the Future," Koolhaas investigates contested country and an uncertain future, but the results are about as clear and visually appealing as the absent cows. After all that, can Marina Zurkow and Sarah Rothberg rely on interactive media and intuition for the limits to growth in high tech and plain old water?

Within the museum's rotunda, the floor bears any number of hazy cutout images—spinach, farm equipment, a cute Japanese robot, the covers of Silent Spring and The Origin of Species, creatures bred the old-fashioned way and genetically engineered. If they never quite add up, they are only a provocation and a summary of what lies ahead on the ramp. With "Countryside, the Future," Koolhaas investigates contested country and an uncertain future, but the results are about as clear and visually appealing as the absent cows. After all that, can Marina Zurkow and Sarah Rothberg rely on interactive media and intuition for the limits to growth in high tech and plain old water?

The two percent

The Dutch architect, now on the faculty at Harvard, made his reputation as much with his ideas as his buildings. His Seattle Public Library uses angled shapes and cantilevers to expand seemingly in all directions because that, to him, is what cities do as well. He has written of them as "programs "as much as places—or, given their tendency to dispersal, a thing of the past. No wonder a report from the UN World Urbanization Projects came as a shock to his urbanism. Not only are cities not going anywhere, it proposed. They already house half the earth's population on only two percent of its space.

Is that sustainable? The question sounds trendy enough, but Koolhaas is questioning trends. At a given moment he might be celebrating or targeting anyone from hippies to China's central committee. He established AMO, a spin-off of his Office for Metropolitan Architecture (or OMA, a firm that also starred Zaha Hadid) to explore the pace of change. Now he brings together AMO's Samir Bantal, the Guggenheim's Troy Conrad Therrien, and students at four institutions of higher learning as fellow investigators and curators. They have produced not so much an exhibition as a text.

Only just try to read it. It is massive enough to defeat anyone, even with ample highlighting to rub it in. It also curves above one's head, on the underside of the ramp, interrupted by the Frank Lloyd Wright bathrooms and pillars. It lands in fragments on the ramp's inner edge, on the low walls protecting one from falling to one's death. Its challenge to the city belongs there, along with its challenge to you. Wright created the Guggenheim Museum as a massive ego trip, but also another urban fantasy—a delight for tourists but a nasty challenge to New York City and its grid.

It does come with illustrations, including photographs, magazine and album covers, and works of art. Chinese screen painting, Nicolas Poussin, and Jean-François Millet all had their pastoral and agriculturally productive landscapes. A Dutch painting by Paulus Potter supplies the missing cows. All appear, too, only in reproduction. "This is not an art show," wall labels insist at least twice. I'll say.

It is also, they insist, not about architecture or science. There have been terrific shows of art and science, art and biology, art and data, art and natural histories, or art and nature. This is not one of them. While globalization, pollution, climate change, and digital waste loom over all, its questions are more existential than practical. "What is the difference," Koolhaas also asks, "between the Cassini Orbiter and God?" I guess the Cassini mission to Saturn is the more unquestioned success, at the cost of abandoning planet earth.

It is also surprisingly sentimental. Just when you thought it had dismissed nature as a postmodern construct, it asks to recover it. "The countryside is not pure, but at least its struggles are more 'real' "—give or take, I suppose, the quotation marks. "In the countryside, you can be anything, including yourself." And just when you thought that it slammed the guardians of power and profit, OMA turns out to be advising China's leaders. Better hope it is asking them questions, too.

To question rationality

Is it too late for answers? While each tier of the ramp has its own stated theme, with its own puzzling starts and dead ends, one can almost make out a narrative. First comes the Postmodernism and the "village of nowhere." What is this countryside anyway, and who created it?  Text tracks efforts not just to idealize nature, but to realize utopia, from Chinese gardens and ancient Rome to Marie Antoinette. It also has the first of several breaks for fashioning nature in mass culture—from country music and Better Homes and Gardens to child's toys and a sitcom featuring Doris Day.

Text tracks efforts not just to idealize nature, but to realize utopia, from Chinese gardens and ancient Rome to Marie Antoinette. It also has the first of several breaks for fashioning nature in mass culture—from country music and Better Homes and Gardens to child's toys and a sitcom featuring Doris Day.

Already you can see the show as itself a fiction—and a leveling one, in which everything is at once obvious and obviously false. Can it really equate the stoic self-effacement of Seneca with pomp and circumstance at Versailles? Does country music really devote itself to a pastoral ideal? (Try telling that to the Man in Black.) Who remembers that sitcom anyway? While the show seems at time to throw in everything but the kitchen sink, perhaps disdainful of modern plumbing, it keeps making some awfully arbitrary choices—much as in its odd handful of western paintings.

After the opening fictions, power gets real, along with the transformation of nature. A composite photo has a forbidding array of twentieth-century males, pen in hand to sign off on its destruction, including Hitler, Stalin, FDR, and Chairman Mao. Again, the implicit alliance is suspicious. Is the New Deal really the same as the collectivization of agriculture—or the Great Leap Forward the same as the Nazi dream of "blood and soil"? Whatever links Manifest Destiny and artificial rivers to "unlimited sexual practices"? Is the next tier's emphasis on "experiments" their extension or antithesis?

The experiments include African cities, renewables, living "off the grid," and genomics, as well as AMO's own in China. With every hope comes a fear, like a Fox News warning of "coming insurrection." And after the experiments comes a tier for present-day epiphanies, about threats to permafrost, coastlines, sea routes, and gorillas. Ettore Sottsass of Italy's Memphis design group had his, as have the creators of "ecological economics." Will they be enough? Just when you thought so, the final tier rips into what it calls a "Cartesian euphoria," with even the world's oceans brought into the grid.

"Can," then, "we both restore and question rationality?" It may depend on what counts as rational. It sure sounds rational to question humanity's place in nature. It is surely rational to call attention to extinctions and to ask what can be saved. It is not so rational to construct a deep history from repetition and sound bites, like a novel built from the author's favorite quotes. It may leave one in that village of nowhere.

For all the show's urgency, it has an unsettling way of standing outside politics. It speaks of movements and ecosystems, but it seems unable to take sides. One might never know, say, that one political party in America is out to undo environmental regulation and design for climate change, including emerging ecologies. One might leave thinking of both as cultural constructs or failed experiments—or, as for Rindon Johnson, just a blip in the Atlantic Ocean. One might leave, too, buying into that party's hostility to American cities and the coasts. One might be better off after all with today's news, a good book, or actual works of art.

The virtual stuff of life

Water is the stuff of life—unless, of course, people have poisoned it and reduced it to a dumping ground for plastics. Unless, too, electronic devices have already stolen the title. Marina Zurkow and Sarah Rothberg cannot offer you a drink, except virtually, but then they do not offer to charge your phone for you either. And they do create a digital and sculptural environment. You might even find it refreshing. As the show's title has it, art and science have their own "Wet Logic."

It begins drily enough, with their Toilet Joke. Blue plastic pellets cover the seat of a toilet, all but nailing it shut. (Just try to find relief on the way to the galleries these days, now that the new Essex Street Market has made its restrooms for customers only.) They might have accreted there over geologic time, and the artists speak of the gallery's front room as existing in just that. They ask how much humanity has disrupted that "linear history," to the point that the planet is "unable to flush away more waste." (Rest assured that they use recycled plastic.) Sure enough, an iPhone peeps up from the pellets, supported by them.

If this is a joke, it entails a grim sense of humor. Still, the phone displays a soothing, silent video of ocean waves, their pale blues set against the darker pellets. Both plastics and devices, they suggest, can mimic and bury the stuff of life. The artists collaborate again with a fishbowl seething with its own currents, as Study for Toilet Joke. Did the final version of the joke take on a virtual life of its own? Will either version come down off its pedestal?

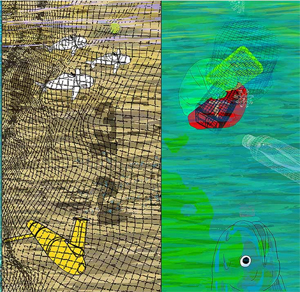

Their solo work begins in stark low tech. Zurkow's wall of Accretions, in ink stamped on cardboard packaging, traces another commercial history, filled with ice cream and human hair, but also an earlier generation of kitchen waste. Sardines descend from a ship like, depending on your degree of optimism, a ladder up or torpedoes. Images have the brute style and dystopian sci-fi references of an earlier Modernism. Tall videos of the ocean's depths update her dark vision as Oceans Like Us (pun intended), accompanied by soothing music, algae, and fish nets. If a clear plastic bottle and milk carton are sinking, fish are rising, and one can always hope for them or for us.

The gallery has dedicated itself to the promise of interactive media since its opening nineteen years ago in Chelsea, as with Casey Reas, Daniel Canogar, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Daniel Rozin, and Lynn Hershman Leeson. Here the screens convert the room into an aquatic environment, in a style between naturalism and a cartoon, as if daring you to tell the difference. And things get more interactive still with the latest twist on that vision, thanks to Rothberg. If you cannot get access to a toilet, you can still flush one, in virtual reality, as Water Without Wet. You can also raise a glass, only to spill its liquid in small but steady drops. You just must share the cryptic space with a bright ocean sky and, now and then, the dark silhouette of a woman.

The drops seem unlikely to land on a house plant that sometimes enters the picture. Proverbially, too, they cannot fill the sea. Still, they seem to belong to a single stream extended across artists and media. A vital future here seems both unlikely and hopeful, as do the ocean's odds of outlasting human beings. I have tried virtual reality since my first attempt at the former Moving Image art fair, and for once I did not feel as if I were about to trip or turn into a cyborg, although I hardly lasted the full eight VR episodes. If I did, I might at least fall into the sea.

"Countryside, the Future" ran at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through February 14, 2021, Marina Zurkow and Sarah Rothberg at Bitforms through March 15, 2020.