Building on Climate Change

John Haberin New York City

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I've tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

—Robert Frost, "Fire and Ice"

"Coal + Ice" and Sustainable Architecture

Climate change is simply breathtaking. So it is at Asia Society—not just coal dust and flames choking the air, but an epic multimedia experience that the Star Wars or Marvel universe would envy.

This is "Coal + Ice," where breathing is anything but easy, but what can clear the air? The Museum of Modern Art is less concerned for futuristic visions than for practical response, in eco-conscious design. Where would environmentalism be without architecture?  Nowhere, of course, when so much depends on building for a sustainable future. And that task, it argues, is well underway. It tracks decades of "Emerging Ecologies."

Nowhere, of course, when so much depends on building for a sustainable future. And that task, it argues, is well underway. It tracks decades of "Emerging Ecologies."

Breathtaking

"Coal + Ice" should have anyone taking a deep breath at what climate change means for the very near future. It may humanize the apocalypse, almost to the exclusion of policy and politics, but the human stories at its heart hit home, and so for all my qualms does the visual overkill. Is this the future of planet earth? It must seem so, in a show that ranges from video to texting. Yet it is rooted in photography from the last century, when the costs had already begun to hit home. Separating the past from the future, it wants to say, is up to you.

"Coal + Ice" must sound like a mistake. Surely the proper pairing is "Fire and Ice," as in a poem of that name by Robert Frost. For Frost, they were metaphors of how the world will end, in desire or hatred. For Asia Society, they are fact and visceral sensation. Coal dust is what blackens the face of a miner in a photo by Song Chao, the worker already sinister and laden with chains. Ice is what is in retreat, even as it still cloaks Everest, in a flight over the Himalayas by David Breashears.

Fire is spreading, too, in video of wildfires by Noah Berger and of drought in California's Central Valley by Matt Black. Like melting ice, these are consequences of climate change, with burning coal its most potent contributor. They and more fill a single large room as a sweeping immersive experience. Photos and video by dozens of artists play out on monitors and museum walls, from floor to ceiling. While one end of the room has coal and the other ice, with fire in between, there is no set entry or exit. Things, they seem to say, will continue without end until people say otherwise, starting now.

Photographs out front document each step in the narrative, from coal to ice. Geng Yunsheng photographs Chinese miners dragging their burden across dry hills and at rest underground, with no certainty that they will ever see the light of day. Camille Seaman has icebergs from both the earth's poles, her photos saturated in blood red and ice blue. Gideon Mendel adds the consequences of climate change for India, where flooding has left homeowners literally underwater. Yet he means to show not despair but a return home. One man has begun to ladle out the water with a steel tub.

Is it a good start or a sadly comic ending? Such is the dilemma of climate change, which droveHelen Mayer and Newton Harrison to their Portable Orchard and survivalism. A man in water up to his neck recalls a young black male popping up from a manhole in a classic photo (now in the Dean collection) by Gordon Parks, with much the same mix of comedy and fear. Parks himself puts in an appearance, with his own photographs of miners, as do Lewis Hines and Bruce Davidson, while shots of factory towers include Bernd and Hilla Becher. And here, too, something may sound all wrong. What is one to make of a group show of nearly forty artists, some who have never set foot in Asia?

A step inside provides a breathtaking answer. Credit the enormous photo and video collage to the curators, Susan Meiselas (a Magnum photographer in her own right, now on view at the International Center of Photography) and Jeroen de Vries. Identifying the contributors for each image is next to impossible, even with a plastic card just outside. If the show is flawed, it is less by dogmatism than by just that cinematic flash. As a poster upstairs asks, "What good is the house on the hill when the valley is on fire?" Here not just the landscape is fiery.

Facing catastrophe

That poster belongs to one of a handful of special projects, which are immersive in a very different way: they serve as hopes for the future and actions for you, in the present. They can be as modest as a poem, by Jane Hirshfield, or as extravagant as a vision of New York in 2050, by Superflux. Make that two visions, of shortness of breath and long relief. They open with dark skyscrapers consumed in a deep red mist. And then a second chamber imagines a greener, wetter New York, with every boulevard a waterway or a beach.

Both chambers place you at their center, facing your own reflection in a mirror. It can be a proud or embarrassing encounter, and it is not the show's final demand. Jake Barton sets out postcards with still more fiery, futuristic images—not just for your enjoyment, but for your signature on the back and an invitation to "chat with your future self." Pull out your phone, text "The Accelerator," and read what you can do in reply. Maya Lin is more welcoming still, with an interactive Web site for global climate information. Lin, whose credentials as an Asian American include her architecture for New York's Museum of Chinese in America, has been committed to the intersection of art and climate change for some time.

Their technology leaves what once were "new media," in Asian video and photographs, in the dust. Still, for all their optimism, the projects raise their own doubts for the future. Has New York in 2050 converted automobile traffic into a day at the beach, or has it made the best of rising seas? Jamey Stillings takes his video camera to renewable energy, but the windmills look eerily close to white crosses in the mega-video a floor below. Clifford Ross, whose questions about climate line the stairs, heads on headed straight for the New York coast for a hurricane—a seeming tidal wave aimed at him. "Coal + Ice" wants to supply an antidote to fire and despair, but neither is all that far away.

As for the view at MoMA, surely a change from climate change really would be nowhere without planners to build away from endangered species, burning lands, and rising seas. Nowhere, when architecture and urban planning can capitalize on urban density to fight suburban sprawl. Nowhere, when everyone deserves easy access to mass transit, parks, wilderness, and gardens, for greener cities in a greener nation. Nowhere, too, when buildings themselves can reduce their carbon imprint and their shadow. It could have the added payoff of more affordable housing without cookie-cutter houses. They could become responsive to nature, responsible to nature, and self-regulating.

Well, surprise, for environmentalism is not just a vision of the future: it is a vision of the past. The Museum of Modern Art finds "Emerging Ecologies" going back at least seventy years—and peaking long ago. Yet it stakes that claim on ignoring almost every one of those needs for the future. But then it is really asking a different question altogether. When it sees architecture as essential to environmentalism, it means to the birth of environmentalism and its very existence, not its potential.

Well, surprise, for environmentalism is not just a vision of the future: it is a vision of the past. The Museum of Modern Art finds "Emerging Ecologies" going back at least seventy years—and peaking long ago. Yet it stakes that claim on ignoring almost every one of those needs for the future. But then it is really asking a different question altogether. When it sees architecture as essential to environmentalism, it means to the birth of environmentalism and its very existence, not its potential.

The curator, Carson Chan, takes the long view. A time line starts with the Tennessee Valley Authority, the New Deal program that provided electricity, flood control, and economic recovery—and, as its next date, the dropping of the atom bomb. If that already sends mixed messages, "Emerging Ecologies" ends soon after 1970 and the first Earth Day. It has no room for stronger federal regulation, greener lifestyles, cleaner skies, and a growing recognition of climate change today. It has no room, too, for the grayer architecture that long ruled. It has no time because it looks back to an alternative that barely existed.

Enclosing nature

Did environmentalism really peak long ago, and did architecture inspire it rather than the other way around? A show subtitled "Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism" opens with Buckminster Fuller and Frank Lloyd Wright, although almost all their urban visions never came to be. It can hardly help doing so, because the public cannot get enough of Wright's Guggenheim Museum and Fuller's utopias. It can hardly help it either because they were on to something, and others knew it. Aladar and Victor Olgyay, who used vents to ensure a "comfort zone" of temperature and humidity, worked in 1956, just ten years after Fuller's Dymaxion Dwelling Machine. Eleanor Raymond and Mária Telkes designed a glass Sun House, a fitting sequel to Wright's 1937 Fallingwater.

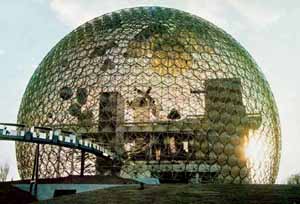

Still, that is slow progress, and it should set off alarms. Wright had designed a unique luxury home in western Pennsylvania that few will ever see. Fuller's proposed machine depends on a mechanical nightmare within a harsh aluminum dome. Soon enough, his more inspiring geodesic dome became the U.S. Pavilion to an international exposition, Murphy & Mackey were adapting it to a Climatron in Saint Louis, and Eames Office with Kevin Roche and John Dinkaloo were constructing a National Fisheries Center in the nation's capital. They, too, though, can seem more a self-indulgence than a model for today. When the Cambridge Seven imagine a rain-forest pavilion like a tropical snow globe, they are not preserving nature but enclosing it.

When Fuller himself proposes a glass dome over Manhattan, it looks merely silly. When a group called Ant Farm hopes to open a "dialogue" with dolphins, it may sound like fun. When Michael Reynolds conceives of a six-pack as the "basic building block" of a beer-can house, it is simply chilling. It is nothing less than marvelous when Carolyn Dry designs a port city close to dolphins, based on coral's natural growth. It is nothing less than essential when Wolf Hilbertz outlines the restoration of a coral reef. Still, sometimes humans should know when to leave nature well enough alone.

Environmentalism thrives on data, and architects can help collect it. Ian McHarg and his students make a long-term study of the Delaware Upper Estuary, and Willis Associates has its Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis (or CARLA), while Fuller's World Game is no more or less than a world map. Still, that map takes up as much space as a football field. Environmentalism also thrives on science, and NASA or Princeton's G. K. O'Neill has every reason to think about space colonies. Discovering the laws of physics will take long observation up close. Still, can taking the human footprint into space seriously reduce it on earth?

The problem is not an excess of idealism. It is what counts as environmentalism. The story really does end too soon. Other shows have called for "Space Between Buildings" and garden cities, but not this show. If anything, it calls for suburban sprawl. James Wine does with his Forest Building, and so does Malcolm Wells in going underground, even if he covers his suburb with soil. Protests have their place, like those of Anna Halprin, a choreographer, but they are not green architecture.

Maybe the problem lies in taking them too seriously. These are indeed idealists, and their environmentalism has less to do with design for a healthy future than with inspiring. Eugene Tssui creates images worth remembering with his wind-generated dwelling. So do Ralph Knowles with his "solar envelope" and Glen Small with his "green machine," of trees on a tiered roof. I have never seen a model of Fallingwater as large as the one at MoMA. More than anything that came after, it takes my breath away.

"Coal + Ice" ran at Asia Society through August 11, 2024, "Emerging Ecologies" at The Museum of Modern Art through January 20. Related reviews look at shows of art and climate change and at artists and architects who takes them seriously, Buckminster Fuller and Maya Lin.