Voices from Earth

John Haberin New York City

You May Go: In Practice 2021

Rindon Johnson and Rachel Rosheger

Where were those voices? They belong to a tantalizing and frustrating edition of "In Practice" at SculptureCenter.

I passed the front desk, where an Amazon package was leaking its contents onto the floor. Had the staffer ordered lunch over ice? I descended to the basement, from a display of weathered landscapes and a pristine skyscraper by Rindon Johnson. I could not stop hearing voices, most often from work I could not see. Like the entire show, they sound enticing, but the artist's meaning remains, even for me, short of explicit. But could Johnson's crossing oceans and continents be any easier to pin down, and can he and Rachel Rosheger save the planet from climate change and a digital world?

Pride and perplexity

I was watching unfamiliar faces float past, but their closed lips could not account for the words—in a language I could neither recognize nor understand. I was puzzling over coarse models by André Magaña, but the air was filled with the cries of children from somewhere else again. I was watching a two-channel video, in which a young man and woman speak of his recovery from a near-fatal illness. They never once exchange a glance or a word. I missed altogether at first a lone voice at the foot of the stairs. As I returned to listen, she seemed more distant still.

The basement tunnels hold SculptureCenter's annual "In Practice" series of emerging artists, like "Total Disbelief" in 2020 and "Literally Means Collapse" coming up in 2022. Almost anything can look marvelous or lost there. Four of the eleven works are in part sound art, but they speak most insistently when one cannot pin them down. Catalina Ouyang records herself and her mother reading poetry together in Danish, but in the shared absence of a Zoom meeting. She also records the crackling of fire, and the closed lips belong to one of two classic movies. She has altered their complete footage to distort its faces.

Leslie Cuyjet recorded those children at play, and her swimmer on video has the center lane of an Olympic pool, but he competes with no one but himself. Sunny Leerasanthanah and her young man speak in Thai (with subtitles), and their Exit Interview is all about recovering everyday connections. So is her installation, which also includes the sick man's watch, shirts, meds, journals, and hospital ID. Still, the man is only an actor, in place of her now-dead father. Dominique Duroseau, the voice by the stairs, speaks of the invisible and history—concerns that come into focus as she insists that "this black body is a landmark." Still, she wonders, "how do I find myself?"

In the comforting words of the show's title, "You May Go, but This Will Bring You Back," but back to what? Leerasanthanah hardly knows—not even whether to return to Thailand. "Are you proud," she asks her father, "of who I am today?" Abigail Lucien alludes to race when she works in cocoa butter, but it takes the shape of bricks on the floor and an incomplete corner wall. Goodbye yellow-brick road? Kyrae Dawaun creates his own nutrition, riffing on mass-produced cold cereal, but I passed on samples for sale at the desk.

Magaña attends to her heritage, with computer accuracy. Those seeming totems, toys, and fruit are not clay but 3D prints, after relics from Mexican tombs. They seem hastily abandoned all the same. Carlos Agredano packs a block of ice into that Amazon package, its water from the Rio Grande and the notorious prison on Ellis Island. He wants to remember Amazon's sharing data with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement—but pity the guy at the front desk who has to mop up after him. I gave up altogether in ascribing gender to a pearl-studded black jacket from Quay Quinn Wolf.

Like Duroseau in search of herself, they speak at once of pride and perplexity. They work best when they take responsibility for not bringing anyone back home. Chiffon Thomas leaves a crumbling black wall of ceiling tiles, plus pillow foam in the shape of milk crates. Do the underground tunnels look familiar from the subway? Hugh Hayden, who will appear next summer in Brooklyn Bridge Park as artist and curator,sets out an MTA bench covered with spikes. Pride or perplexity can be a deadly burden for art, but get ready for a long ride home.

An early sunset

When it comes to the art scene, you may think of yourself as in the know, but watch out: wherever you are, in London or New York, Rindon Johnson is ahead of you. Just thirty-one, he has a show coming this fall at Chisenhale gallery—but with a preview now an ocean away in Long Island City. You may want to call the trolley repair shop your favorite alternative art space, with its architecture by Maya Lin, but Johnson has a head-start there, too. Arrive at noon, and you may find a gloriously sunny mid-afternoon, covering an entire wall. Come a little later, and sunset will already be giving way to night. .

Not that it will ever be too hot, even in summer. Johnson picks a vantage point for his video in the North Atlantic, midway between London and New York, in what hard-nosed scientists call the Cold Blob. Whatever happened to the Gulf Stream? Blame it on climate change if you like, in a show about human intervention gone out of control, like Jumana Manna, on political oppression—and both for such artists as Josh Kline mean massive unemployment. Still, sunlight on vast, rippling waters has to look picture perfect. Just beware of a perfect storm.

Not that it will ever be too hot, even in summer. Johnson picks a vantage point for his video in the North Atlantic, midway between London and New York, in what hard-nosed scientists call the Cold Blob. Whatever happened to the Gulf Stream? Blame it on climate change if you like, in a show about human intervention gone out of control, like Jumana Manna, on political oppression—and both for such artists as Josh Kline mean massive unemployment. Still, sunlight on vast, rippling waters has to look picture perfect. Just beware of a perfect storm.

A cynic might complain that all sunsets, like all dog pictures, are alike, whatever addicts say on Instagram, but Johnson begs to differ. He translates real-time data into an ever-changing image—or maybe not so real, since he relies on data from the year before. See, not even he can keep up, but forecasts are like that. His show's title, "Law of Large Numbers," refers to the principle in statistics that small samples deliver less accurate predictions—or the principle in finance that booms and busts eventually even out. Either way, hot and cold streaks will not last. Yet global warming is not going away any time soon.

The artist is fond of sunlight and water. Stained glass refracts the light, while its near-abstract black, white, and blue suggest a swimmer by Henri Matisse. After weathering in the pebbled courtyard, rawhide now hangs like a hammock overhead, where it holds rainwater that visitors will never see. Much else, too, is inscrutable, like a smaller projection that seems never to change. Someone has roped off trees and fenced off a more distant patch of green, but why? A single tall sculpture occupies the large, high-ceiling central space, abstracted from the outlines of the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, but how does it belong with all the water?

I have no idea, although an insurance company must know something about large numbers. Not that the Bay Area native is hiding anything. If anything, his exhausting titles are painfully explicit. Up to well over a hundred words, they sound like bad attempts at Beat poetry or the rants of a crazy old man, right down to the occasional cuss words and full caps. I would give you a taste (beyond a small excerpt in my photo credit), but you may have neither the screen space nor the patience. Besides, they are as inscrutable as the art.

Johnson seems torn between a sense of beauty, as with the Minimalist pyramid in gorgeous brown wood, and an impending darkness, like that premature sunset. Another hide, weathered in a Brooklyn backyard and scrunched up on the wall, rubs one's face in its ugliness. The dichotomy may reflect the painful experience of a trans person of color all too aware of his body. In a work's title, "it has occurred to me that I exercise to make myself cheaper for my insurance company" (which may or may not be Transamerica). He wants to know, he says, "if our bodies can break the law of large numbers." Probably not, but who knows about art?

The perfect storm

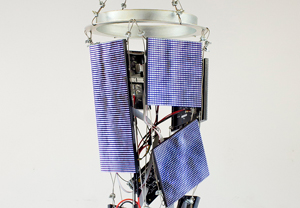

A storm blew in from Brooklyn. It brought with it some hefty but fragile sculpture, some elusive imagery, and one of the few galleries anywhere with a commitment to digital media—and, for now, the only one in Chelsea. Rachel Rosheger opens a brand new space for Microscope with what at first glance might seem hastily thrown together. Are those high-tech scraps, the kind increasingly spoiling the planet, or maybe worse still low tech, and what is flickering past on screens no bigger than a tablet? For Rosheger, the questions are connected, in a show called "Gone Before You Get There," and they leave unsettled the fate of Bushwick as well. It may take art to sustain it or to create the perfect storm.

Those small screens display an array of white dots nearly too large and too well spaced to count as pixels. It makes one all the more aware of the rods, custom cables, and microcontrollers driving them, holding them together, and suspending them from the ceiling— or otherwise raising them off the floor. Not that it is easy to resist the flicker or trying to pin it down. I found myself scanning the black screens and shifting points of light for people, because that is a habit pretty much anyone has in a time of YouTube, surveillance cameras, facial recognition, and African American deaths. I had almost given up when I spotted storm clouds, but maybe I should have given up sooner. The constructions are intriguing enough in themselves. So is another unsettled question, their place in the present.

or otherwise raising them off the floor. Not that it is easy to resist the flicker or trying to pin it down. I found myself scanning the black screens and shifting points of light for people, because that is a habit pretty much anyone has in a time of YouTube, surveillance cameras, facial recognition, and African American deaths. I had almost given up when I spotted storm clouds, but maybe I should have given up sooner. The constructions are intriguing enough in themselves. So is another unsettled question, their place in the present.

Rosheger works with lightning rods. Not that they no longer have a use, and Lightning Field, a classic of Minimalism and earthworks by Walter de Maria from 1977, still stands in New Mexico thanks to the Dia Foundation. One can think of the new work as making accessible the drama in de Maria's flashes of light. Still, lightning rods have been around a long time, and an additional work leaves tips from obsolescent rods on the floor. Their bulbs, with three of their five spikes serving now as tripods, have turned rust green, as if they had been around for a very long time. But then white on black can give the illusion of sky blue.

The screens may be the ultimate in low-res, but not blurry, so stand back and one really can make out sunlight and storms. That, too, looks back, to cloud studies in art by John Constable. As for him, the storm systems need not blend together, and they take on added relevance in the face of global warning. As the saying goes, everyone talks about the weather, but no one does anything about it. Maybe so, but the first step in facing climate change is talking about it and countering denial, and art can play that role, as with tropical storms for Teresita Fernández. Besides, Rosheger's constructions make good use of the latest thing.

That still leaves much unspoken, but at the very least it brings new media back to Chelsea. The only other gallery with a stake in the matter, Bitforms, headed downtown seven years ago—and the New Media art fair last appeared in 2017. The two galleries also have distinct profiles. Installations for Bitforms run to crisp but fluid surrounding images, illusion, and virtual reality, while Microscope favors disordered assemblies and technology itself. Rosheger's images keep one looking because of it. If she relies on toxic waste, that is an environmental issue, too, and assemblage is a kind of recycling.

The state of the art looks good, then, but not for Brooklyn. Microscope was hardly the last gallery standing or even the last in its building, but massive Bushwick open-studio weekends are a thing of the past, and excuses to visit are fewer, too. Nor is moving a guarantee of survival. Where today are the Williamsburg galleries that tried Chelsea—including that of Edward Winkleman, who wrote a book about running a successful gallery and directed Moving Image? Williamsburg's oldest gallery, Pierogi, has retreated home after a welcome stretch on the Lower East Side. Its show by Andrew Ohanesian about real estate for rent has taken on a bitter irony, and one can only hold out hope that this gallery and the earth have a future.

"In Practice" and Rindon Johnson ran at SculptureCenter through August 2, 2021, Rachel Rosheger at Microscope through June 12. Bitforms moved to the Lower East Side in 2014.