Small Gestures and Big Alphabets

John Haberin New York City

By a Thread, Lee Mingwei, and Paul Glabicki

León Ferrari and Mira Schendel

Critics still like to argue about who is saving or killing art. Is conceptual art submerging real experience, or is irony a healthy recognition of one's limits? Is painting liberating or self-indulgent? I hate to name names right now, but it gets tiresome. Much of art stopped fitting the categories years ago.

More than a few shows in 2009 did not. They involved writing and drawing, and it got hard to tease out which was which. They played with sign systems, but an accounting ledger could easily morph into calligraphy or calligraphy into thread. If they anything in common at all, it was an accumulation of small gestures. If anything makes installations right now stultifying, it is money and the consequent need to make an impression. These shows settle happily for small impressions.

One show even calls itself "By a Thread" and another "Paraphrase." Each has threads without a fabric and alphabets without words. Lee Mingwei even makes others bring their own fabric, while he offers to mend it. Still other artists erase images of fabric or save the lint. One can call them all post-minimal in their ordinary materials, except that they have a way of filling a room.

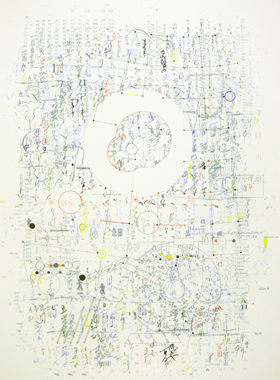

The work of Paul Glabicki from a distance looks empty, but it combines Asian calligraphy with western accounting. At MoMA, León Ferrari and Mira Schendel define a path through Modernism that anticipates them all. It lies outside Europe all along, but also well within tradition.

Threadbare

"By a Thread" implies a fragile existence, but what exactly is hanging by a thread? To judge by a group show, it may not be art. The media include photography, wax, copper wire, and acrylics. They also insist on the survival of painting, with the dealer's customary formal bent. Holly Miller's lines of thread, for one, shade and stretch color-field geometry, in pale landscape tones of blue and green.

They do accept decay, like Elana Herzog's fabric remnants on a supporting column. They may also simulate explosions, like Mary Carlson's blood-red Wiresplat. Mike Asente has a wall of widely spaced embroidery, each titled Ground Explosion or Air Explosion. The black threads, set off-center on small white fields, might have rained down as shrapnel. A larger burst radiates outward from a circle on the floor. Elisa D'Arrigo sews her cloth over surging lumps, like sugar cubes or tiny volcanoes.

In other words, they show signs of life, and if anything is hanging by a thread, it is that. Lesley Dill uses thread on a muslin silkscreen to give a man Rapunzel's hair. "I see visions," reads the text over a shadowy woman. "I was born with a veil." Edward Shalala photographs his own drawings in white thread on black ground. They look as ghostly as a photogram.

Just as they do not stick to thread, they do not survey its uses in contemporary art. They do not include the Minimalism in soft materials of Fred Sandback or Richard Tuttle. They do not recover native or craft traditions, like Brooklyn's Sackler Center and many others. Ann Shostrom comes closest to tapestry as art, but in a dense, messy mix of wax, embroidery, and colored dye. Although most here are women, not all are, and they do not insist like Ghada Amer on female sexuality. One might think of the eight artists as one theme in a much larger show, and they gain from that.

Just a year ago, in fact, a slew of galleries gave my imagined show more rooms. Thread served as abstraction, as decoration, and as construction of space for such artists as Angelo Filomeno, Jonah Groeneboer, Tomás Saraceno, and Cui Fei. The last returns in "Paraphrase," where the emphasis is on a kind of wordless writing. Her Manuscript of Nature takes an entire wall for what looks like Chinese but on closer inspection has a much smaller alphabet.  Her thread ties together small twigs in mostly vertical and horizontal strokes, like a solitary soul ticking off the days. Its materials are of nature, but also like nature in their slow process of creating the visible.

Her thread ties together small twigs in mostly vertical and horizontal strokes, like a solitary soul ticking off the days. Its materials are of nature, but also like nature in their slow process of creating the visible.

Minette Mangahas, too, emulates calligraphy like as much as many a Chinese-American artist today, but she also plays more explicitly with the gap between abstraction and text. Brushy curves find their way across one wall and, here and there, onto paper. Other traces, in ink and silver pigment, occupy two translucent sheets like successive pages, but also like layers of a painting. The sole artist who actually writes anything, Aakash Nihalani, also simplifies things that much more. His strips of colored tape look like Sol LeWitt wall drawings for remedial school kids. In the past, his geometric outlines have defaced subway tiling, and here he alludes both to graffiti and public signage, with the I of the word EXIT neatly framing a back door—giving me a good place to take my leave.

Tangled up in blue

For all the associations of thread with the human hand, one can easily forget that sewing has a practical function. Even when art recovers weaving, it recovers "woman's work" exclusively for the arts. It will not help with the state of my wardrobe.

Lee Mingwei might, or at least he makes the offer. One can bring torn clothing to his gallery, and he will mend it. Of course, this being art, there is a catch or two. One must leave one's garment till the end of the show, and the thread must not match. One can pick from dozens of colors, though, on spools that irregularly dot the gallery walls. Clothes pile up on a center table, each labeled with its owner—and each thread still connected to the wall.

Mingwei plays with color and texture, but also something beneath the surface. A work of art has associations with restoration and with caring. One can think of them as art's unconscious, and Heidegger made care a central ethical and esthetic need. Traditionally, art recovers things as they were, including memories of them. It also reflects an artist's love for them, the materials, and the work. Mingwei recovers the goods, up to a point.

For one thing, they will bear his mark. The disruption extends to "women's work," too, since he is obviously male. The work includes his table and two chairs in the back room, where he works and talks with customers. Soft-spoken but gregarious, he clearly enjoys it. In other words, craft has become a process, and the work will rise or fall on how active that process is. After one week, with only a small pile and a very light weave of color filling the air, it was too soon to tell.

Thread can mend, but it can also come undone. For a time the Lower East Side has a show of wisps and traces, and they can look delicate or even wistful, but not at all comforting. As conceptual art, they sound downright confrontational. Mary Kelly collects lint, and Christian Capurro erases an entire issue of Vogue. Klaus Mosettig projects a blank screen onto canvas and traces the imperfections. Beware of art, and beware of fashion statements.

For additional distancing, Capurro displays enough text to fill an even more off-putting magazine, he asked others to do the erasure, and one must take it on faith that one actually can erase a glossy (which I gather was indeed possible with the quality of paper and ink at the time). He may also allude to one of art's most elegant and subversive gestures ever, Erased de Kooning Drawing by Robert Rauschenberg. Mosettig, however, very much speaks of caring—with both the work by hand, much indeed like Rauschenberg's, and the memories of predigital slide projections. So does Kelly in arranging the lint into a virtual desert, inscribed with a woman's first-person statement of displacement and loss. It spans a row of photos like a beachhead or combat zone. Who am I to complain if her series, begun before Operation Desert Storm in 1999, could correspond to pretty much any politics and any war?

Settling accounts

When Paul Glabicki stumbled on a Japanese ledger book from the 1930s, he felt that he had found a precious artifact. Then he had to add to it—or perhaps to cover it up. Calling the past to account just was not enough.

"ACCOUNTING for. . ." consists of sheet after sheet, each covered with Japanese characters, tiny Arabic numbers, and Roman letters. They come in ink and many-colored pencil, in dozens of complete and fragmentary columns. They tempt one to account for them—to decipher them and to figure out their system. Even so, they have no intention of adding up. It takes a moment to realize that the numbers far exceed the original accounting. Nor is it easy to know what came first.

For starters, one has the two sets of characters, from two continents. One has two nations and two decades, both separated at the very least by a world war. One has two kinds of care and compulsion, too—the accountant's work and the artist's play. Overlays, gaps, and clustering call attention to the layering. The pale pencil colors can approach the transparency of writing on Plexiglas. They run to lists—powers of ten, metric prefixes, the chemical elements.

Glabicki includes diagrams as well, from plane geometry, elementary physics, and architectural elements. Indeed, they have in common precisely their function as elements. They also blur the distinction between visual art and alphabets, science as art and natural histories, much as Japanese will to most Americans. A wall of folded but unaltered sheets preserves the visual appeal of the original writing. Many artists pursue a system to the point of claustrophobia, mania, or chaos. Glabicki is drawn not to a system but to systems.

Other artists have recently straddled abstraction, portraiture, and arcane languages. Melissa Brown disperses cryptic images through the triangular cells of interlocking hexagrams. Think of a Web browser designed by Buckminster Fuller. The patterns, snakes, and folding money (value $000) in other paintings have an early 1970s' paranoia. They do, however, keep the puzzle of representation alive. And the month before, Carrie Moyer made that puzzle all the more haunting and sexy.

Moyer calls her show "Arcana," but its meanings are less arcane than fluid. She paints with thin acrylic washes, so that colors dance across an image. Titles like Ballet Méchanique and Tiny Dancer relate the dance to both early Modernism and pop culture. A totemic goddess—her hips like a tabletop and her breasts as eyes—brings the dance back to its bottom line, sex. A row of helmeted silhouettes is less static and less predictable, right down to its title Frieze (rhyming with "Freeze!"). Moyer hints at universals, but she also goes with the flow.

Ferocious alphabets

These shows straddle so many alphabets, materials, and signs that it is easy to lose track. They go well together, in fact, mostly because of that. They seem like nothing so much as a repudiation of Modernism and Postmodernism alike. Did the first boast heroic gestures and pure painting? Did the second announce the death of both? No one seems to care.

Even that, though, overstates the change. The "postmodern paradox" still holds: the opposites keep one another alive. The post-structuralist argument for images and philosophy alike as a kind of writing still makes sense, so long as one does worry about what it spells. The argument has also helped in another way. It has also helped bring out small, conflicting gestures in Modernism all along.

Modernism has a history of systems and their destroyers, going back to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Think of such extremes as Lewitt and Alfred Jensen. Surrealism and automatic writing, too, have the appeal of a system that defies conscious systems. Cubism should look different now. Late Pollock—once derided as too figurative, too empty, and too personal—should look better.

The Surrealist impulse to ferocious alphabets survives at MoMA. Both South American artists there in 2009 started out in the 1960s. León Ferrari sticks most to modernist strategies, but with a contemporary payoff. Free writing becomes drawing, wire sculpture compresses space, and collage that updates Christian art for the nuclear era. Although Mira Schendel died in 1988, she reaches further—to another dispersal of systems in the plural.

Brazilian by way of Switzerland and Paris, not unlike Lygia Clark, Schendel writes in half a dozen languages all by herself. At least she does except when she displays blank sheets, wads of paper, or a volume of thread hanging from the ceiling. Multiple copies of the letter A rest suspended in glass—waiting for a letter press that has become an endangered species. All the same, she wants one to attend to the poetry of the text, about love and winter.

These artists have the appeal that one never can settle accounts, and all three invoke the old-fashioned pleasures of close reading. Most even depend on that close encounter, for from a distance Glabicki's sheets or Mingwei's volume of threads looks bland or even empty. Others from a distance actually seem too busy. Of them all, Schendel left something most translucent and productive of new alphabets.

"By a Thread" ran at Elizabeth Harris through July 24, 2009, "Paraphrase" at Arario New York through July 24, Lee Mingwei at Lombard-Freid through November 14, Paul Glabicki at Kim Foster through May 9, Melissa Brown at Canada through July 12, Carrie Moyer there through June 7, and León Ferrari and Mira Schendel at The Museum of Modern Art through June 15. Mary Kelly, Christian Capurro, and Klaus Mosettig ran at Simon Preston through January 4, 2010.