Looming over Tradition

John Haberin New York City

Elias Sime, Suzanne Goldenberg, and Tapestry

Julia Bland, Talia Levitt, and Rags

Why is tapestry looming so much over art these days? Is it about challenges to art or markets hunger for more? Is it about trends or tradition?

Art has no end of both, and artists get to choose for themselves. Elias Sime finds his sources of tapestry in Africa and used electronics, but then a circuit, too, is a weave. Suzanne Goldenberg in Minimalism and trust in the artist's hand, and Julia Bland in abstraction and Native American art.  Each can look to feminist, anti-imperialist, or cultural pieties, in order to bring things back to the vital present. They also supply a handy occasion to survey more broadly the pressures and the options. For one last twist, eight years later Talia Levitt gives only the illusion of tapestries and calls them rags.

Each can look to feminist, anti-imperialist, or cultural pieties, in order to bring things back to the vital present. They also supply a handy occasion to survey more broadly the pressures and the options. For one last twist, eight years later Talia Levitt gives only the illusion of tapestries and calls them rags.

Tapestry of a nation

Talk about the perils of the art market. Elias Sime spends much of his days at the Merkato, the open-air market in Addis Ababa, and the results can be worth a fortune. Not that he is so fine a scavenger, although one could find almost anything there, or so the story goes. Not that he is even so determined, at least on the surface. His assemblages would not work half as well without an air of spontaneity. He just has a good eye for color and for the emerging picture of east Africa. He is assembling the tapestry of a nation.

Make that reassembling, on at least two levels, and at each level the tapestry has more than one weave. At the level of materials, it includes the debris of everyday life, like buttons and bottle tops. It includes older memories, in shells, horns, and animal skins. Most of all, it runs to a whole new wasteland, of circuit boards. Each has the notion of assembly already built in, and each has already become dated, including the electronics. Each, too, Sime implies, is not about to go away.

At the level of imagery, the tapestry again borrows from both the First and Third Worlds, in what a show of craft at the Whitney calls "Making Knowing." Sime has his abstractions, and chance plays its role much like drips for Jackson Pollock. Assemblage derives from Robert Rauschenberg, only these are "combine paintings" in a sense that Robert Rauschenberg never intended, for they take the form of large curtains in two dimensions, like actual paintings. The largest look most explicitly to African art, with lighter colors and tapestry patterns. In between in scale are aerial maps with clear patterns of navigation, like apps. A villager would not have had that perspective before the electronics.

Sime wants it both ways, and he largely gets it—junk and craft, first and third world. He asserts both Africa's place in the modern world and the cost. "I treat them like oil paint, acrylic, or clay," he says of his materials, and he has a point, given his bold designs and still bolder colors. That way, too, an upscale gallery gets to market them as extravagant art. At the same time, he insists that the rest of the world serves as a dumpster for the West, with such nonbiodegradables as plastic and circuitry. The Merkato itself mediates between the two stances, active and passive, as a place for him and others to gather and to throw away.

If the artist wants to have his waste and eat it, too, he is hardly alone. Much of recent art has claimed both dignity and pop culture, as well as both sex appeal and a critical spirit. Sometimes it succeeds at that, although then there is Jeff Koons. Installations as trash piles are common enough, and Sime deserves credit for sticking to something more like painting. He also fits with a wave of recovery of craft traditions. Often that comes with a specifically western history of folk art, as with Miriam Schapiro, and he gains interest by pointing insistently to Africa.

In all this, he has an obvious predecessor in El Anatsui (the work pictured just above). Although nearing fifty, Sime is a full generation younger, and one could easily write him off as castoffs from the other. When the older artist presents rippling curtains of gilded metal, the kind that seals liquor bottles, the younger, too, is recycling abstraction while recovering native art and wasted lives. He has the fair excuse, though, of his correspondences between layers. He also has the pertinence of crisp patterns and present-day waste. Real politics and real conflict pretty much fall by the wayside, but not Africa's potential for orienting itself to the future.

Crafting Minimalism

A woman's work is never done. The recovery of craft for art has progressed so far that one can easily take it for granted, with Anni Albers and as a contribution to women in postwar abstraction—or, with Katarina Riesing, the female body in art now. For Suzanne Goldenberg and Julia Bland, though, it is still unfinished business. Each combines areas of fabric with open weaving, and each looks to more than one tapestry tradition, and neither is African. Goldenberg even weaves into her work a loom or two—or is that itself a construction and an illusion? Bland looks back further still like Jimmie Durham, Alan Michelson, and Esteban Cabeza de Baca to Native American tradition,  but also with still more open air. Yet she, in turn, also has a greater taste for polish and perfection.

but also with still more open air. Yet she, in turn, also has a greater taste for polish and perfection.

Goldenberg incorporates strips, cords, finer threads, and coarser sheets. Few run larger than a napkin, and even that looks hastily stuck to the wall. Patterns have a way of emerging, but also spilling out and apart. They can serve as a study in textures or as a sign of their own making. A couple really do look like looms, and they have the sole bright colors. Their dissonance alone might prevent the weave from coming to completion.

Bland has larger, more colorful, and more cleanly geometric compositions. Most hang vertically, with diamonds in striking symmetry, often doubled like paired animal skins or human bodies. They might fit right in with the actual Native American wing of a museum. They might also fit with geometric abstraction from a time that shunned texture or gesture. Yet they still have plenty of views onto the wall, where the thread separate. And that, too, has something in common with Minimalism.

Not so long ago, art had no time for craft, maybe especially after abolishing gesture in favor of industrial materials and appropriation. Ceramics and fabric alike were not exactly ways to endear an artist to galleries. Now both are everywhere. The Lower East Side has a tea ceremony by Takuro Kuwata, not so very far in time from Andrew Long in Chelsea, Bruce M. Sherman on the Lower Eas Side, and a whole compendium of "Vessels"—over and above such usual suspects as Ken Price and Arlene Shechet. Hangings influence artists who rely on unstretched canvas and who use weaving as design. It has led to shows of rags and banners, but also alternative views of the late Renaissance.

Neither has a strictly feminist impulse, although both give greater scope for a feminist art history, like that of Dotty Attie. They may even recover a little ground for Modernism. MoMA still has its design collection, and the twentieth century still has the Bauhaus. All-over painting worked so hard to distinguish itself from decoration in no small part because it seemed anything but different. Bland's colors and diagonals also have something in common with the irregular polygons of Frank Stella or the regular polygons of Bernard Kirschenbaum. And, speaking of tradition, Stella did name a series Polish Villages.

What counts as complete, what as present, and what as personal? Goldenberg has her loom, Bland her spread. The first allows stains and tears, while the second insists that ground alone serves as image. The first is also more concerned for the artist's touch, the second for imagery, with titles that speak of winter and ashes. Yet she also presents work that one could more easily roll up and take away. Like Sime, both suggest that art after Modernism is still a work in progress.

Rags and bones

When William Butler Yeats wrote of "the foul rag and bone shop of my heart," could he have meant it as a compliment? Not entirely, but for Talia Levitt the foulest rags are dear to her heart. They evoke the European Jews who came to America and founded a garment district on Orchard Street, not far from her Lower East Side gallery today. They evoke the stale air and foul working conditions of immigrants in the Triangle Shirtwaist factory, barely a mile away—and the fire that cost more than a hundred their lives. They evoke the scraps of lives that she encounters on the streets and in the subways every day. That fire took place in 1911, but for Levitt past and present are equally alive.

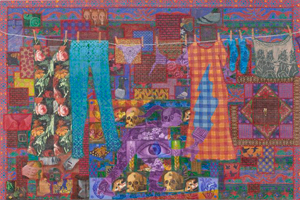

Not that she is celebrating, but neither is she simply lamenting. She is remembering. Where tapestries have grown popular as materials for painting, she gives the illusion of quilting in paint. This, after all, is not the rural South but the urban jungle. The show's title, "Schmatta," Yiddish for rags, may sound funny, provocative, and comforting as well. You might mistake it for a spread or a sentiment, like schmaltz.

In reality, the word has overtones of the downtrodden and despised, like those dressed in rags or like a doormat. And no wonder, for Levitt makes a point of anonymity. For her, names lost to history mean as much as lost lives. Her patches of fabric are rudely stitched together, if only as an illusion. A fire hydrant keeps popping up, no more cheerful for its bright yellow, and a discarded coffee cup, the kind from a bodega or Greek diner, lies on its side. Commuters assembles women's faces and subway stations, but this will be a long, silent ride.

Her rag and bone shop has its bones as well. Like Cecily Brown, she places herself in the tradition of Flemish and Dutch still life, with its love of illusion and fear of death. Flowers and skulls speak of mortality, and Levitt has plenty of both. She works both freehand and from stencils, and the repetition, too, is both comforting and disorienting. Images divide a surface into patches the size of postcards, while the mechanics divide it into tiny squares. Where Georges Seurat had his Pointillism, she has her cell division.

Unlike Seurat, she has little interest in stillness, because nothing for her stands still. It just keeps coming back. Her past work has much of the same elements, but now the images weave more fully into the imagined fabric. They allow colors and contrasts with a little glitter. They are also less obviously personal than earlier pills and shells. They reach back into Jewish history and out to a broader picture of New York.

The room upstairs has glitter and textiles, too, but the real thing. Sara Jimenez makes an installation or a maze of it, as rain from dreams or from breaths. She leaves just enough room to circulate around the work, but not without touching its sheer fabric, buttons, and beads. A sign warned people to approach with caution at the opening, and I wish I could have joined in after a drink. Jimenez shoots for the sheer experience of rain, dreams, or breaths. One must head back downstairs for the details.

I far prefer the details, all the more so because Levitt makes them hard to pin down. It leaves her work less didactic and brings its memories more alive. Yeats was paying himself a left-handed compliment. After the lyricism and bombast of his early work, which he evokes here in his cadence and his diction, he shifts in the course of the poem to common language, with everyday disruptions. He has left only "a mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street" and his heart. The poet in his seventies has found street smarts and schmatta, and so has the artist.

Elias Sime ran at James Cohan through October 17, 2015, Suzanne Goldenberg at Molly Krom through October 4, Julia Bland at On Stellar Rays through October 25, Takuro Kuwata at Salon 94 Freeman through October 24, Andrew Long at Barbara Gladstone through May 30, and "Vessels" at Blackston through May 3. Talia Levitt ran at Rachel Uffner through June 30, 2023. Related reviews look at tapestry in art, Gee's Bend quilting, and art and fashion.