Not Backing Down

John Haberin New York City

Joan Mitchell and Susan Rothenberg

Joan Mitchell was asking for it. Starting in the 1950s, her vivid colors and feathery touch turn their back on the agonies and ironies of Abstract Expressionism. Yet she was not just backing down.

It allowed her to expand on the movement's epic scale, all-over compositions, and powerful gestures. At the same time, it made her the founder of something altogether new, color-field painting. So was she the culmination of America's most ambitious movement or its antithesis? Does it matter that she ditched New York itself for Paris? A retrospective makes it harder than ever to minimize her art. A generation later, Susan Rothenberg undertook the same argument with painting, one that persists to this day.

Absent landscapes

Did Joan Mitchell "feminize" postwar art? Her white spaces can easily sound precious compared to a formalist's grid. Hints of landscape can make her the gentle mother after a generation of male action heroes. Think of Vir Heroicus Sublimus, Woman I, Lucifer, or a drip painter's automatic self-portraiture. Forget the background, they seem to say, in favor of objects to be worshiped, ogled, or feared.

In an excruciatingly male domain, it hardly helps that Mitchell bears the label "second generation Abstract Expressionist," meaning painfully derivative. Hardly a year or two earlier, male critics took such gutsy women as Janet Sobel and Lee Krasner for granted, as so often did Jackson Pollock. What, then, could they make of Mitchell? She seemed a follower of Modernism, just when art was moving to a theater beyond painting. Besides, she literally followed a man, a prominent Canadian painter, to settle in the Paris suburbs. And yet she was always so much more.

Her retrospective should rescue her once and for all from the role of abstract art's push-over. In its very first room, Mitchell takes on the boys. The dense, irregular tiling recalls Krasner—but also the enamel patches of Willem de Kooning from his very first solo show, the somber browns of Arshile Gorky after a fire consumed his happiness and his work, and the assertive brushwork of Jackson Pollock in his own earliest abstractions, like Mural.

In no time, too, she is her own woman. Her canvases start with the background as a thing in itself, the carefully slathered white paint creating wide-open spaces or coming forward in crusty, subtle relief. Big horizontal strokes then define a painting's structure. Against all this, drips descend vertically, and finer drawing in oil weaves the layers together. She has taken each of the elements of a drip painting, but recombined them in a totally conscious construction. As the layers intermingle, the idea of feminine background and male foreground slips away as well.

A decade later, much as in late Pollock or Mark Rothko, colors darken into black. She also discovers symmetry. Paired shapes and separate panels stare back at one another, as if daring paint to define an object after all. In her final decades, canvases open up again, often on a monumental scale, but the play of symmetry continues. A single block may take up different positions in three panels, like a house recalled from long-faded snapshots and distant stories. Her scrawls of color, like unreadable handwriting, attain a final lushness, not unlike late work of Cy Twombly and far from the later sensibility of Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Mitchell has no trouble taking on the guys, and she can do it without the heavy baggage of male competition. If women also appreciate flowers and finery, like a friend in the New York School, Jane Freilicher, fine. Abstraction can incorporate landscape, she showed, so why not still life as well? If Pollock drips on the floor to leave his mark, her drips carry downward within the field of art. They orient a painting, whereas her blocks of color float free of its gravity. If Pollock makes one identify painting with his presence, her loose, open spaces mark her and painting alike as absences.

The beautiful light

"The thing that really makes me want to puke is these artists who feel like they have to go to the South of France because the light is so beautiful. I find that bogus. The light in California is hotter than the light in France." Speaking to the Sunday New York Times Magazine in 2005, Ed Ruscha might not have had Mitchell in mind, but I wish I had them together with me. It would have made for a lively argument. Her affront to macho perspectives might extend even to the battle over freedom fries.

Actually, Mitchell moved to Paris, not the Midi. Besides, in work from 1960 to 1962, back on view in New York, she may come closest to the ideals of "epic abstraction." Should one see landscape in her open backgrounds of the 1950s? It is inescapable in the regular shapes in her late paintings, like ponds or garden plots. Not even Jennifer Bartlett before her "Hospital" pastels has created such an elusive garden idyll. Still, her Frémicourt paintings, after her studio address, put paint literally front and center.

Mitchell prepares a light ground, its white itself a lush beginning. Over that she uses broad horizontal brushwork to assert symmetry, clarity, and an overall tonal range. Last, palpable swirls of oil all but leap off the canvas. The work has the dense layerings and sharp colors of de Kooning in the late 1950s. They have the strongly centered compositions and improvisatory air of earlier Pollock. And, as with Pollock throughout his life, black becomes the most intense color of all.

Perhaps she needed a certain distance from New York and the 1950s to make it her own. Perhaps she needed to work through it alone, before assimilating it to her earlier, more horizontal compositions. Perhaps she was unleashing the sheer joy of returning full time to France, a decade after her student year abroad, and of taking up with Jean-Paul Riopelle. Perhaps, but in the depth of oil and bright color may yet have something to do with a new light. They could recall that Claude Monet had set a prescient earlier pattern for all-over paintings and for the modernist impulse to work in series. Then again, those de Kooning abstractions struggle with the piers, lots, highways, and open air of New York City.

In those same years, Ruscha was observing, too, and he was seeing a much less natural light. His early paintings bring to Pop Art the artificial light and black skies of the California highway at night. In 1965 he paints the Los Angeles County Museum on fire. Now there the light was hotter than in France.

Mitchell, like Sonia Gechtoff, asserts her independence of first-generation Abstract Expressionism without Ruscha's combativeness or the harsh, aggressive reality of traffic on the Pacific Coast Highway. Her light definitely never recalls puke. Mitchell has often escaped labels, just as she once escaped the New York art scene. With his own distance from New York, I hope that Ruscha would understand. Laconic precision can take art only so far, when a painter like her can take command of excess.

X marks the spot

Postmodernism has sought Mitchell's unique combination of excess and absence ever since. It has allowed women artists to embrace illusion, play, and disguise. They can tackle images from a male tradition while speaking for themselves as women. They can refuse to be simply leftovers, however you number the generations.

One can see the same interplay of gender and tradition in older art as well. New art has a way of making the past look different, and new exhibitions can insist on it. With Artemisia Gentileschi and others, museums have brought those antecedents alive. I thought of them all, but especially Mitchell, as I hit the galleries. Kara Walker was showing women as literal blanks in history—black cutouts, projections, and the whiteness of refined sugar. Pat Steir carries Mitchell's structure of grid, drips, illusion, and scale into a subject matter of mist and waterfalls.

One can see the same interplay of gender and tradition in older art as well. New art has a way of making the past look different, and new exhibitions can insist on it. With Artemisia Gentileschi and others, museums have brought those antecedents alive. I thought of them all, but especially Mitchell, as I hit the galleries. Kara Walker was showing women as literal blanks in history—black cutouts, projections, and the whiteness of refined sugar. Pat Steir carries Mitchell's structure of grid, drips, illusion, and scale into a subject matter of mist and waterfalls.

Steir made her name with New Image painting, an implicit affront to years of No Image painting. Another of its finest exponents, Susan Rothenberg, plays the other to Bruce Nauman in her personal life—and in her latest show. If his 2002 video leaves people as mere hints of a larger world, she lets them intrude directly, but on a painting's edges. White dominos spill across her mottled green surfaces. One glimpses the limbs that set them in motion, like the odd feet of a younger painter like Cyrilla Mozenter, but barely and without a clear space or narrative in which to place them.

Rothenberg's freely but carefully worked ground and flickering white remind me of Mitchell. Both indulge in sheer pleasure, but from an unfamiliar angle. As with abstraction since Pollock, Rothenberg's scenes are often poised between accident and violence. Objects may tumble to the ground, from tables overturned in a moment of anger at losing a child's game. They may parody male aggression as itself for children.

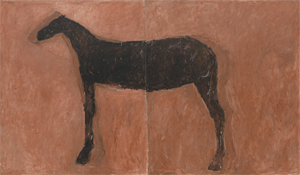

Rothenberg's early signature pieces outline a horse in motion, against a flatter, more barren field of paint. Sometimes a large X across the center anchors the horse as object within a field, even as the horse disrupts formalism. The X against the horse's limbs heightens their extension, letting a woman appropriate the physicality of a traditionally male symbol. While she identifies painting with freedom and buried memories, she did not pick horses out of love. And the X cuts across the horse, as if to obliterate it along with illusions and machismo. It identifies painting as an anonymous sign, the signature of a woman struggling to sign for herself.

Rothenberg can no longer claim a struggle. Her show opens a new location for Sperone Westwater, extending Chelsea galleries and their market reach down into the trendy Meatpacking District. (It has since left for the Bowery.) Certainly nothing in her latest work haunts me like those horses, but sometimes the green background comes close. Did Mauman's Clown Torture already parody the innocence of childhood more than any clown face by James Ensor? Call her work a parody of a parody if you like, but it drives the image home. She makes anonymity her mark.

Joan Mitchell ran at The Whitney Museum of American Art through September 29, 2002, and her Frémicourt paintings at Cheim & Read through June 25, 2005. Susan Rothenberg ran at Sperone Westwater through June 1, 2002. A related review picks up Susan Rothenberg twenty years later, in focus at the Museum of Modern Art.