Horse Sense

John Haberin New York City

Susan Rothenberg and Louise Bourgeois in Paint

"Negate painting as much as possible, in terms of illusionism and shadow and composition." Susan Rothenberg did not mean it as a directive, but merely an explanation. She must have felt that she had a lot to explain.

Was imagery for those who just did not get the message about modern art? Believers in "pure painting" said so, when Rothenberg painted her first horse. It helped launch New Image painting and made her impossible to overlook. But why that image? Had she recovered the power of the body in art—or its negation? Her own answer may sound more like a defense of the abstract art that she had left behind.

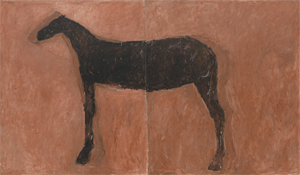

Triphammer Bridge, from 1974, was not the first, but it could be the hardest to explain or to forget. Why turn to a horse for work on canvas, and why darken and flatten its profile, leaving little more than an outline and an eye? Why bisect the horse at that, by painting across two canvases? And yet it was an image—and as earth-shattering a turn as painting has made in the half century since. Along with a handful of other works at the Museum of Modern Art, it offers a retrospective in miniature and a sense of why, despite it all, painting persists. So does Louise Bourgeois, who explored the gendered body in paint before turning once and for all to sculpture.

Fifty-five years before Femme Couteau (or "knife woman") in sculpture, there was Femme Maison. If that sounds less threatening, Bourgeois began as a painter, of spare but unsettling means. The body for her was not yet a weapon—and not yet too scary and too precious to touch. In four versions of the painting, from 1947, a house was her only covering, descending to her waist, and that was enough to stifle her. A "house woman" is not so very far from a housewife, and Bourgeois would have found that role stifling as well. With just under fifty works, the Met shows her brief course as a painter and her emergence as something more.

Those were not her only homes, all with ample room for her. Not that one would know it from her paintings, and two of them share a corner at the museum. One is The House of My Brothers, with family or strangers behind gated windows. The other depicts her home in New York, from the outside, not far from Gramercy Park and Stuyvesant Square. One could call this a tale of two media or a tale of two cities. I prefer to remember a tale of two houses and two homes.

Double negative

When it comes to Susan Rothenberg, it is hard not to stumble into contradictions. That horse, its plain red background, and its shining black coat have become so totemic that surely horses for her had a personal meaning going back to childhood. But no, she insists. The very absence of meaning is what makes it possible to seem at once a negation and larger than life. (I have since had to correct my review twenty years ago of her work in the galleries, along with another pioneering woman artist in Joan Mitchell.) She herself stumbled into them in that provocative statement.

No illusions? One can feel a powerful body in space, just as for Bourgeois and Eva Hesse in sculpture. Paint spatters in brighter colors make the horse's coat all the more vivid. A larger profile in a darker red surrounds it—if not a shadow then an aura. The line dividing the diptych reinforces the composition, at right angles to the horse's side and in parallel to its front legs. The rear legs tilted slightly back add to the sense of motion.

The curators, Cara Manes with Lydia Mullin, fall into the trap, too, to their credit and Rothenberg's. They speak of her "dirty whites, warm blacks, and muted reds," but I had never appreciated before the vividness of her red or the clean white behind a second horse, also at MoMA. A set of six paintings from 1988 turns to looser brushwork and brighter blue. They, too, are about motion in space, inspired by Joan Jonas and a dance company, like successive frames in a single performance (a subject for Robert Rauschenberg as well). All the better that the last in the series shifts to white and the connection between frames never does add up. All the better, too, that the second frame has extra limbs, for either a dance partner or a further echo of stop-action photography.

The six paintings count nonetheless as separate works, with a history about as far from the avant-garde as one can get. Rothenberg conceived them for the six pillars of a corporate dining room. After years as a waste of museum space (and a model for the waste of space in others), the atrium has held up pretty well since MoMA's 2019 expansion. It has done so by mocking its resemblance to storage space, with Amanda Williams, or, with Adam Pendleton, to fire escapes. Here it thrives with work from the museum's holdings and an artist who thinks big. It reflects a new emphasis on the permanent collection, which now gets the rest of the second floor as well.

Rothenberg thinks big without ever needing a mural scale. She is, after all, negating painting. She may not intend that as a directive, but critics back then made it one and artists listened. One could put her words in the mouth of Donald Judd, who gave up painting for Minimalism, or Ad Reinhardt before him. One could put it, too, in the mouth of conceptual and political artists when painting as on the outs. Rothenberg saw how the negation of painting could allow it to thrive.

Others in the movement saw it, too, like Neil Jenney and Jennifer Barlett, but Rothenberg seems all the more prescient for the revival of painting today. (As guest curator at MoMA, Amy Sillman has singled her out.) The formula could apply to Frank Stella a decade earlier as well—or to Julian Schnabel smashing dinner plates. her insistence on motion has, if anything grown fiercer and her intrusion into the third dimension harder to decipher. Dogs kill a rabbit in 1992 while she and her husband, Bruce Nauman, look on, comic or cruel, in the cartoon styling of Donald Baechler, and the dismembered legs of marionettes descend pathetically from a green bar in 2008. Yet a horse's apparent stillness remains her most formidable attack.

A tale of two houses

Not ten years before The House of My Brothers, Louise Bourgeois was new to New York and a newlywed, but hardly a housewife. She had studied at the Sorbonne and opened a gallery in Choisy-le-Roi, a wealthy suburb of Paris, when Robert Goldwater walked in the door. They were well matched. Her family had a gallery next door, specializing in rare tapestries. He was an art historian specializing in Africa and ancient civilizations. He wrote Primitivism in Modern Painting and created (god helps us) the "primitive" wing of the Met, while she mapped the dark unconsciousness of the present. Her gallery had been ambitious and progressive enough, with such artists as Eugène Delacroix and Henri Matisse, but who would have imagined how much her art would overflow its shelves and its cages?

She moved to be with her husband, who taught at New York University, and she loved the city, although one would never know that either. Her apartment in paint has a blood-red interior and what might be blood on the floor, were it not a ghostly white. There and elsewhere, she lies in isolation on the floor or wide awake in a narrow bed. Rest for her is always hard to find. She may have looked to New York for just that restless spirit. Her building has long given way to an apartment tower's dreary white brick.

She moved to be with her husband, who taught at New York University, and she loved the city, although one would never know that either. Her apartment in paint has a blood-red interior and what might be blood on the floor, were it not a ghostly white. There and elsewhere, she lies in isolation on the floor or wide awake in a narrow bed. Rest for her is always hard to find. She may have looked to New York for just that restless spirit. Her building has long given way to an apartment tower's dreary white brick.

She had known home in France, too, but as a source of guilt and obligation. She grew up above the gallery, and she had only recently nursed her dying mother. She paints herself bringing flowers to her father's grave as an act of atonement. Now in New York, she blamed herself for deserting her brothers, who enter Confrérie (or "brotherhood") as black profiles beneath a mammoth storm cloud. The family's mansion appears behind them, immense in its width but tiny in perspective. It might well be a state prison.

Not that she is ever passive. She strides across an early painting, doubled above by herself swimming. Still, confinement is everywhere, along with savagery and independence. Three women stand atop a tower, crying for help, but the huge female creature sweeping in from the sky is hardly an old-fashioned hero. Another building is little more than empty yards and concrete walls, with a watery ground. She based it, she said, on the Louvre.

Jackson Pollock had to work his way through Surrealism in America, on the way to a new kind of painting. Bourgeois in those years had to work her way through painting to achieve a new kind of Surrealism in sculpture. She segued easily in time into Post-Minimalism. Already in paint, her bare outlines and dull red grounds anticipate Rothenberg, while the bulging shapes of her sculpture anticipate Eva Hesse. The Met throws in a few sculptures to round things out, like Dagger Child, with a greater confidence and aggression. She was not, she must have realized, all that great a painter anyway.

Even a modest show could be overkill, after a Bourgeois retrospective at the Guggenheim in 2008, Bourgeois prints at the Met in 2018, and claims for "Freud's Daughter" at the Jewish Museum in 2021. (By all means follow the links to past reviews for more than I can say here.) Still, one can see how the paintings fed into her sculpture. Their buildings went into its gridded architecture—and the gendered body into everything she touched. Her fears give way to mammoth spiders and her guilt to The Destruction of the Father. Still, till her death in 2010, a woman bears the pain.

Susan Rothenberg ran at The Museum of Modern Art through June 12, 2022, Louise Bourgeois at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through August 7. Related reviews look at Susan Rothenberg in the galleries, Louise Bourgeois in retrospective at the Guggenheim, and Bourgeois in prints and at the Jewish Museum.