The Empty City

John Haberin New York City

Holly Zausner and Christopher Culver

Katherine Newbegin and Duane Michals

Holly Zausner walks though a city without a community, New York, but in all its majesty. But then video and the gallery create their own community.

Maybe connections are always fragile and elusive. Just ask someone like me who grow up here. Christopher Culver in charcoal lends New York a greater warmth, but it, too, seems forbidding and apart. They have some impressively lonely company in photography as well. When Katherine Newbegin and Duane Michals document cities, they find the comforts of movie theaters, hotels, and the early 1960s, but also a high vacancy rate. It may even free them up.

Arresting images

Holly Zausner makes arresting images, but then she takes things slowly herself. She hovers above her worktable, rearranging small photos over and over, as if unable to decide where they belong. She stands dead still in Times Square, her back to the camera, while people bustle past. She walks ever so deliberately through an empty New York, dressed as always in black, each step echoing on the soundtrack. Perhaps she cannot freeze others, but she can eliminate them from her art, and so she does after Times Square. One may never see those familiar streets and landmarks without human traffic again.

She calls the video Unsettled Matter, and plenty remains unresolved. Where is she heading, face front along a median strip? What is in those photos on her worktable, and what is she seeking in them? What is she doing in a harness anyway at arm's length above them? What happens to her or to them when she lands? As the scene loops between her studio and her travels, has she recovered without injury, or has her slow journey come to a crashing end?

Still, much seems quite settled. She sure does, arms swaying by her side. She is taking possession—including possession of what for most viewers will be their most cherished memories. She takes over Film Forum for a showing of L'Avventura, the 1960 film by Michelangelo Antonioni all about a slow pace and a looming mystery. She takes over the Great Hall of the Met, Grand Central Station, Chinatown, Broadway north of the Woolworth Building, and more. One can overlook a great deal in exchange for the game of identifying them, although only the film within a film hints at a playful sense of humor.

One might still have qualms about the weight that Zausner assumes. No wonder she crashes in her studio. The gallery insists that she works in real time, and the artist confirms it, but you may find yourself alternately skeptical and marveling. Do people melt into tracks of light, even tourists and commuters—and even under her gaze. Can her stride acquire that firmness and those production values on its own? And somehow they do.

They also get one thinking. This is not simply a love letter to New York or a documentary—but then what is it? What connects its two parts, the studio and the streets? Is this the life of the city or the alternative reality of a dream, like painting and film itself for Salvador Dalí? What happens when an experimental film claims those lavish locations entirely for itself? Thankfully, the Mayor's Office of Film and Television took care of things, in a city truly supportive of the arts.

Clearly something is happening well beyond mere self-dramatizing, something meaningful indeed. Zausner's video and the stills derived from it are attention grabbers. One may not accept her impassive ownership of the city and the media as a feminist statement, but one will remember a woman's presence all the same. One will remember something else, too—a vibrant city as a non-community, in transit and belonging to no one, not to its residents and not even to her. She focuses on sites for commuting and for tourism, and her one truly intimate environment, the Strand, traffics in used books. Here New York's oldest and most personal memories are still unsettled matter.

I'll take Manhattan

Christopher Culver does not exactly have a love affair with New York. His works on paper are too unflinching for that—and too short of explicit human connections. They are a record of his attachments all the same. That includes his attachment to drawing. Charcoal and dark pastel lend his surfaces both sharp-eyed realism and soft-focus texture. Their very intimacy invites one into his life and allows one to mistake it for one's own.

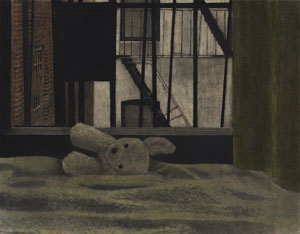

Culver calls his show "Manhattan," and there is no mistaking the city. It has the sidewalks with their awkward drop-off at the curb. One can see how dead birds would have come to an untimely end on the street. It has the views out a window that never quite opens onto rooftops and open sky, with hints of both enclosure and ways out. It has a soft light in that uncertain space between day and night. That, the drawings say, is the space where he lives, too.

Culver calls his show "Manhattan," and there is no mistaking the city. It has the sidewalks with their awkward drop-off at the curb. One can see how dead birds would have come to an untimely end on the street. It has the views out a window that never quite opens onto rooftops and open sky, with hints of both enclosure and ways out. It has a soft light in that uncertain space between day and night. That, the drawings say, is the space where he lives, too.

It recalls the stereotypical apartment that artists can barely afford, with way too little sunlight or starlight at all hours of the day and night. The stuffed animal on a bed must be his, too, in a New York where adults need whatever affection they can get. Not that he ever appears, but then neither does anyone else. Life and art alike have the ability to evoke things unseen while testifying to the visible. Life or art could dissolve at any moment, just as the drawings dissolve into stippling. They are just another way of getting things right and taking care.

He shares the show's title with the "Analog City" where I myself grew up and a familiar movie. Like me more often than I care to say, Woody Allen makes a point of nostalgia, but with his often bitter, rapid-fire jokes. Culver's dead birds, struggling house plants and other unexpected juxtapositions defy nostalgia, and his humor takes things slow. One can move from work to work uncertain what will come next, each with a layering that hides what might otherwise cohere into text or other images entirely. That, too, builds a sense of connection. Back outside, Tribeca's clumsy paving and poorly maintained streets seem off-putting by comparison.

It may seem strange to go from Culver to photography. He cares too much for work by hand—and hardly at all for photography's documentary impulse. It may seem stranger still to cross the continent and to go back in time more than fifty years. Yet all I could think of was the layered black and white of Jay DeFeo more than fifty years ago. A stubborn Bay Area artist, she had finally finished The Rose in 1966, if that is the word for a massive construction whose whole point is never to be finished. Then she moved to Santa Monica for five years and picked up a camera for her own portrait of socialization and seclusion.

She, too, was drawn to still life but cannot leave it alone. The layering can arise from cutting and pasting photos, photocollage, or a staged assemblage akin to Surrealism. It can fall into abstraction, morph into faces and bodies, or become something else entirely, like the old-fashioned telephone that one might mistake for a black liquid pouring down. Maybe I should have thought of Salvador Dali and his telephone topped by a lobster claw. Could the process recall her sculpture after all with its labor of love and hate? Not really, but it makes a fascinating addition to a career so often known for a single work.

Portraits without people

Katherine Newbegin ranges more widely, in search of more humble pleasures. She finds her way from a motel in New Mexico to a youth hostel in Warsaw and to Soviet-era hotels elsewhere in Eastern Europe, not so far from the unmade beds in photos by Laura Larson. She has a special fondness, though, for movie houses. All are "Vacant," in her show's title, but people seem to have slipped just off-stage. Someone must have set down the blue hotel telephone in Moldova or swept the trash from a bungalow in Germany neatly into a corner, and someone might have been using the roll of toilet tissue and woolen glove in a chapel room at Vassar only a moment before. One can almost count movie theaters in Mumbai as their portraits, with quaintly numbered seat backs assigning each a place.

Newbegin calls her subject spaces of transitional occupancy. That relates her photographs to creature comforts closer to home. Back in New York, after all, people may treat a bar as a way station before settling into an evening at the movies—one temporary solace after another. Newbegin's pleasures, though, could easily have become a casualty of empty rooms, displacement, and change on a far larger scale. Hers is a world recovering from totalitarianism and poverty, with people moving on to make their own choices. They just may have to travel a long way before letting go.

Newbegin calls her subject spaces of transitional occupancy. That relates her photographs to creature comforts closer to home. Back in New York, after all, people may treat a bar as a way station before settling into an evening at the movies—one temporary solace after another. Newbegin's pleasures, though, could easily have become a casualty of empty rooms, displacement, and change on a far larger scale. Hers is a world recovering from totalitarianism and poverty, with people moving on to make their own choices. They just may have to travel a long way before letting go.

A long exposure makes the most of their presences and photography's claim to truth. The end of a corridor glows, like the end of a Paris street for Charles Marville, and one source spreads its points of light like a star. Sunlight on partially torn wallpaper simulates a forest clearing in Oregon. When light falls onto a boarded-up movie screen, it could be the start of a cinematic projection. Abandoned spaces often stand for unmet human needs, much as with classrooms caught up in the drug wars in Colombia for Juan Manuel Echavarría. As for Deroo, though, they never cease to promise pleasure.

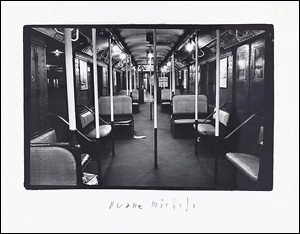

Cities are surely the ultimate in transitional spaces, with all their chance encounters, risks, and pleasures. New York was my transitional space, in what one likes to call growing up, and so it was for Duane Michals around 1964. His Empty New York shares its emptiness and a gallery with Mark Innerst. Michals, like Danny Lyon, values a seemingly quainter city than the painter's broad avenues barreling into depth. Yet his photographs take one past skyscraper canyons and early twentieth-century convention. The thirty prints capture real spaces, without the exaggeration of thick sunlight, and a real moment in time.

New York then still had cul-de-sacs, Hook and Ladder Companies, and a majestic Penn Station. Diners had juke boxes, and subway cars had rattan seats. Graffiti had not taken over—or taken on the cachet of street art and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Michals could look at empty barber chairs, empty tables, and a dry cleaner's promise of same-day pressing and know that they were waiting for customers, perhaps him. "Everything was theatre," the gallery quotes him as saying (with that old-world spelling). "Even the most ordinary event was an act in the drama of my little life."

He found inspiration, too, in the Paris of Eugène Atget, its shops boasting of desires. Still, he must have known that the Beatles and war had arrived, the crowds on the Coney Island roller coaster were getting rowdier, and America was on the cusp of change. He did not have to show the freaks and flagrant pleasures of Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus to know that emptiness is only a transition. He has clean contrasts in place of Atget's warm shadows, and the repeated objects within his compositions, from women's shoes to subway poles, have as much to do with late Modernism's formal strictures as consumerism and private fetishes. His white borders may not be so far from Innerst's thick wooden frames after all, with each print signed. He could stand at a distance without traveling half the world, to know the strange comforts of day-to-day life.

Holly Zausner ran at Postmasters through May 31, 2015. Christopher Culver ran at Chapter NY through December 9, 2023, Jay DeFeo at Paula Cooper through October 18. Katherine Newbegin ran at Lesley Heller through April 20, 2014, Duane Michals and Mark Innerst at D. C. Moore through May 31. Portions of this review on Newbegin and Michals first appeared in a different form on New York Photo Review. Related reviews look at Duane Michals in retrospective and the empty city.