Looking for Modern Art

John Haberin New York City

Georgia O'Keeffe: Drawings

Alberto Giacometti and Barbara Chase-Riboud

How did artists invent abstraction and modern art? More than a hundred years later, museums still marvel at it and ask why.

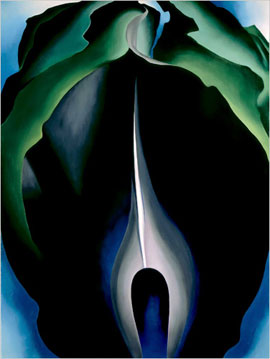

Were they pushing an alternative art to its limits, to the point that it was tethered to no other reality than itself? Were they just plain falling in love with paint? Georgia O'Keeffe was there from the beginning, pushing hard with plenty of love. Back in 2009, the Whitney called her retrospective "O'Keeffe Abstraction," because nothing else seemed so essential. Never mind that her most famous paintings were of flowers and the American southwest, for they were abstract, too, right?  Yet she left everything wide open. As I wrote then, her whitest image is a flower, her most colorful the indefinite space of abstraction, and her darkest a tent door at night.

Yet she left everything wide open. As I wrote then, her whitest image is a flower, her most colorful the indefinite space of abstraction, and her darkest a tent door at night.

Now the Museum of Modern Art has a different answer, and it need not depend on paint at all. It took looking and doing, and a show of O'Keeffe drawings follows her across the continent to do both. At the same time, it singles out a burst of activity, long before those large white flowers that no one could forget. If you think of abstract art as the aftermath of Cubism and Futurism in Paris, with such artists as Stanton-MacDonald Wright, she discovered the same impulse on her own in New York, without his need for overflowing patterns of color. What, after all, could be more modern than New York? How about leaving the confines of city streets?

Alberto Giacometti had never been to New York, but he had plans for Lower Manhattan. When Chase Bank came to him in 1958, he envisioned one of his striding figures, amid the movers and shakers streaming through the bank's plaza. It never came, but seven of his works in plaster are standing tall, also at MoMA, amid work by Barbara Chase-Riboud. They may seem an odd couple—a living artist and a giant of Modernism, a black woman and a Swiss gentleman who had his studio in Paris for more than forty years. Still, thanks to MoMA, his influence is unmistakable, and so is her challenge. Besides, as she titled more than one sculpture, All That Rises Must Converge.

An impulse toward realism

For MoMA, the medium really was the message, as early as 1915, and I do not mean oil. Others have seen a woman as its inventor earlier still—Hilma af Klint, with the cryptic signs of Symbolism. Georgia O'Keeffe, though, did not need mysticism or a private language. All it took was doing. She complains of the wear and tear from so much charcoal, graphite, and pastel. She was rubbing them hard on paper and rubbing her fingers to the robe.

Could that work on paper have led her to the texture of oil? Watercolor could as well, in its transparency and flow. This is stained canvas without the canvas, although the show tosses in a handful of oils as well. The very motion of her hand carried through to her early compositions, with broad parallel curls. A superb survey text of modern art, by John Russell, reproduces a watercolor, not a painting. Its bands rise to encircle a point of light, her Evening Star.

And that takes one to the show's other side, in what she saw. Its first work is the least observed, as well as the densest, with little white space and little light. Already she valued spareness and spontaneity, in single black and blue verticals with a sudden turn toward the top. Already, too, she caught the eye of Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and gallery owner, whom she married. Teaching positions, though, in Virginia and Texas, showed her blue hills, that tent door, Palo Duro Canyon, and a train crossing the plains at night. Travels on her own took her to Lake George a pool in the woods, and lightning at sea.

As curators, Samantha Friedman with Samantha Friedman and Emily Olek put time and ingenuity into tracing her subject, even as it all but disappears into abstraction. O'Keeffe wanted to see it all, but not for its details. What look like branches are features of the land seen from an airplane window. What look like abstract tilings are the piled stones of walls in Peru. Her late move to New Mexico allowed her to linger over what she found in the desert, from a goat's horn to bones. Oh, and she has her tightly cropped flowers, her canna lily and orchid, too.

The display can suggest an impulse toward realism or abstraction, but it cannot rule out a personal connection to what she saw and made. She sketches herself nude, as a way of letting in the color and letting go, with the sexuality of her flowers, and Paul Strand, the photographer, but they have not just separate personalities, but separate styles. She leans forward in the fullness of life, while he becomes a gaunt, ragged strand. When she turns to Beauford Delaney, the black artist, she pays tribute to his skill in portraiture with a face alone and a greater precision. In each case, she repeats a motif several times, watching it take shape. As the show's title has it, "To See Takes Time."

There may be no one answer to what makes her Georgia O'Keeffe. She could collect postcards, work from the imagination, or work from life. After the show's first five years, she made less and less as well—especially as age took its toll. Still, as I concluded in 2009, she found both privacy and revelation, austerity and sensuality. (I invite you to read that earlier review for more.) And that leaves open whether she found them in her vision or her media.

Rising and falling

It is easy enough to number the differences between sculptors. Alberto Giacometti literally got his hands dirty, working in plaster, at times with a pocket knife. Barbara Chase-Riboud begins the old way with "lost-wax" casts, before pouring molten metal into the molds. His figures are gaunt to the point of tortured, hers bulking outward as they rise. Her Woman's Monument might be sustained by its flowing robe——and might be facing down a wall. The small plates of Cleopatra's golden cape, in copper and bronze, glisten.

His figures are of indeterminate gender or color, hers proudly female and black. Still, he identifies his as either men or women, including Spoon Woman from the 1920s and Woman with Her Throat Cut from 1932, neither in the show. The seven plasters round out his Femmes de Venise, all but one from the 1950s. She has her own Standing Black Woman of Venice, black of course, from 1969. A dark obelisk, it looms over his Tall Figure in MoMA's collection, itself larger than his women, on the same platform. She comes closer still to Giacometti with The Couple, a jagged mass on spindly legs, but then her figures are never altogether alone.

Chase-Riboud moved to Paris, too, as still a young woman, and wasted no time in heading for his studio. She likes to remember plaster dust covering everything. It was right around when he was abandoning the commission for Chase, which went instead to Jean Dubuffet. Still, they may get the better site, a room outside the postwar collection. One can see echoes of the wavy surface of her flattest tower in the garden fountain below. Giacometti has engaged viewers directly with his Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object) ever since MoMA's 2019 expansion gave renewed weight to its permanent collection.

Chase-Riboud moved to Paris, too, as still a young woman, and wasted no time in heading for his studio. She likes to remember plaster dust covering everything. It was right around when he was abandoning the commission for Chase, which went instead to Jean Dubuffet. Still, they may get the better site, a room outside the postwar collection. One can see echoes of the wavy surface of her flattest tower in the garden fountain below. Giacometti has engaged viewers directly with his Hands Holding the Void (Invisible Object) ever since MoMA's 2019 expansion gave renewed weight to its permanent collection.

The pairing acts on the museum's promise to rehang the collection every year, with its "fall reveal." Curated by MoMA's Christophe Cherix and Emilie Bouvard of the Fondation Giacometti, which lent the seven works in plaster, turns for hers to the Met, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and private collections as well. All told, she gets the better of the deal. She forms the backdrop on the platform, as if setting the stage for both, while larger and smaller work stands apart to all sides. It has much in common with another spanning Modernism and African American art, Melvin Edwards. He, too, prefers the weight of metal to plaster casts.

She works in another marker of difference at that, raw fibers. They pun on the metal "fabric" of Cleopatra's cape, but they take on a greater weight of their own. They may lie above or beneath the rest, on the floor or suspended from the wall, or work their way into the bronze. No question, though, but she discovered herself only after her student years and her visit to Giacometti. Then all she had to do was to shed his overwhelming influence by getting past The Couple. Also a novelist and poet, she could still keep two things crucial to his work, the human figure and the ambiguity.

Are his in an existential crisis or in command, and is this a tamer Giacometti, without the nightmares? Are his void and his spoon half empty or half full? In the same way, her sculpture could indeed be rising or falling. Her titles speak of Africa Rising and All That Rises (adapted from a Southern white writer, as a matter of fact, Flannery O'Connor), and two parts of Albino may well rise to rise to either side, pinned at top to the wall. Yet the mass of metal and fabric at center seems to have fallen of its own weight to the floor. At eighty-three, with her own public sculpture in Manhattan, she sat through the press preview, and she may find it harder and harder to rise.

Georgia O'Keeffe drawings ran at The Museum of Modern Art through August 12, 2023, Alberto Giacometti and Barbara Chase-Riboud through October 9. Related reviews looks at Georgia O'Keeffe abstraction, Alberto Giacometti in retrospective, and Barbara Chase-Riboud in Chelsea.