The Births of Modern Photography

John Haberin New York City

Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, and Paul Strand

Alfred Stieglitz may have thought of himself as the center of everything, but he was never comfortable playing the role. When he brought New York's two leading groups of photographers together in the 1890s, as Camera Club, he declined the presidency. He lent work to the 1913 Armory Show, which brought Modernism to America, as one artist among many. Asked to curate a show at the National Arts Club in 1902, he called it "an exhibition of American photography arranged by Photo-Secession." He had named a movement, but he acted as if the movement had created itself. In a sense, it had.

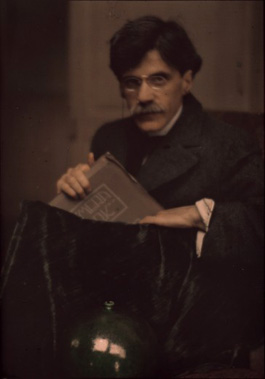

Still, he knew what he wanted, an American photography, and he let others know that it needed him. He founded Camera Club only after photographers forced him off his own magazine, for his domineering manner.  He took advantage of the Armory Show to stage and to promote his own show, at his gallery. In a self-portrait from 1899, he stands at the edge, as if pleading that one look instead at the photograph on the wall. But he is the frame—young and handsome, with piercing eyes and an open shirt collar, a portrait of the artist and of a new century. Besides, that photo on the wall is nearly too small to see.

He took advantage of the Armory Show to stage and to promote his own show, at his gallery. In a self-portrait from 1899, he stands at the edge, as if pleading that one look instead at the photograph on the wall. But he is the frame—young and handsome, with piercing eyes and an open shirt collar, a portrait of the artist and of a new century. Besides, that photo on the wall is nearly too small to see.

"Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand" puts him very much at the center. Maybe not literally so, although he exhibited the other two photographers (and a related review looks at Steichen's commercial photography). Chronologically, he is the oldest. Of the three rooms at the Met, he has the first. However, the show is really about three stages in modern photography and three visions of Modernism. And there the oldest is definitely at the center.

Old world and new

The Met all but says as much, by the entrance to its galleries for drawings, prints, and photography. To one side, George Bernard Shaw carries on his lifelong argument with the Victorian era. Edward Steichen gives him the broad pose and weighty shadow of almost all the photographer's portraits. Like much early photography, it takes painting as a model—in particular, the chiaroscuro of the Old Masters. Its blurred outlines aim for aura and majesty. Modernity, it says, deserves no less.

Across the way runs Manhatta, the silent film by Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler, the painter. If the title here, too, sounds like an invocation of the gods, they are not necessarily benign deities. They also will not sit still to pose. As a title screen says, "million-footed Manhattan unpent descends to its pavements." In just minutes steamships pass, a ferry discharges its passengers, smokestacks and trains discharge their business, and buildings rise from the labor of men and machinery. The camera rises as well—on a skyline familiar even today.

Both the title and title screens quote Leaves of Grass. No doubt Walt Whitman saw himself as a prophet of modernity, and one can see the entire exhibition as the fulfillment of a prophecy. It describes how the city evolved from carriages to motorcars and how photography evolved from chiaroscuro to abstraction. And those are exactly what Stieglitz documents. His gift to the museum also makes up the show, curated by Malcolm Daniel. One can start anywhere, so let me start at its geographical center.

Born in 1879 in Luxembourg, Steichen came to America as an infant. The tension between his old-world origins and Midwestern roots never left. For him, Europe in the evening is a glow upon the water. J. P. Morgan in 1903 rests his arm on a chair like an homage to Rembrandt. In a large-format portrait from 1907, Lady Hamilton's white dress is a study in white highlights and high society. So are silhouettes of buildings and men in 1904.

When Steichen takes art for his subject matter, he brings the same sense of the past. A self-portrait with box camera could come right out of Mathew Brady. Auguste Rodin poses in profile beside his Thinker, naturally thinking. Rodin's Balzac takes on towering proportions, naturally at night. Leaves echo the japanoiserie of the 1890s. Still, this is modern art, and the nude of Little Round Mirror moves from studies in shadow toward a glimpse of abstraction.

The shadows of New York in the same years make the same connection between old world and new. A bare branch crosses the Flatiron building framed by distant streetlights, like a high-tech arcadian vision. The skyscraper's lighter tone and the evening sky contrast with darker masses in front of Madison Square. Again, a search for the painterly leads Steichen to innovation and experiment. In a color process that the Lumière brothers had just introduced, his very subjects, like a woman's flowing yellow dress, show his delight in the process and in color. The glass autochrome plates look almost like computer monitors in low light.

From robber barons to revolution

Paul Strand, born in 1890, belonged to twentieth-century New York and a circle of free thinkers. He attended the private school called Ethical Culture, where he studied with Lewis Hine. Ever after, he builds on Hine's documentary photography and demand for social change, but he pushes it past sociology. He pushes it toward abstraction, like the crisp patterns of the El or of Central Park in winter. He pushes it toward portraits of modern life, with humanity as much more than the masses. A blind woman wears the sign BLIND, but she meets the viewer's gaze, and one is obliged to see.

Strand does not treat these impulses as opposites. A postmodernist might think of formalism and portraiture as two kinds of distancing. One kind exploits people for composition, the other for sentiment or a message. For the photographer, in contrast, they are two forms of engagement. They find beauty in objects, like a chair back and its shadows, and in the objects of oppression, like eyes in the shadow of a hat brim. They bring the camera into the scene, where it cannot look away.

Strand does not treat these impulses as opposites. A postmodernist might think of formalism and portraiture as two kinds of distancing. One kind exploits people for composition, the other for sentiment or a message. For the photographer, in contrast, they are two forms of engagement. They find beauty in objects, like a chair back and its shadows, and in the objects of oppression, like eyes in the shadow of a hat brim. They bring the camera into the scene, where it cannot look away.

They thrive on the tension between the human and the inhuman as the condition of modernity. A still life bronzed by its silver-platinum print looks almost like statuary, as much as a wooden crucifix in a Mexican window in 1933, while white bowls look like flower petals. Wall Street shows a massive building's refusal of ornamentation, as people and their long evening shadows pass its tall, dark unchanging windows. His portraits and architectural views alike rely on lean diagonals where Stieglitz would have seen a whirl and Steichen a shadowy presence. He borrows a title, Man with a Hoe, from Jean-François Millet. Where Millet's peasant looks not so much mystical, noble, or dumbfounded as just plain dumb, Strand's crouching laborer is poised for action.

How does one get from J. P. Morgan and the age of robber barons to an age of revolution? Alfred Stieglitz would not feel comfortable with either one. All the same, he documents the passage from one to the other. With the transition from the bulky box camera to the hand-held, he could begin to keep up. Where Steichen clings to the past while celebrating the present, Strand describes changes as the new stasis. Stieglitz takes change as it happens, one year at a time.

One can see it in a title from 1910, Old and New New York. A skyscraper's frame is going up, but the foreground detail seems left over from another age entirely. At the same time, the metal frame has a depth and quietude that the foreground traffic does not. No wonder it could outlast the horse and buggy. Some twenty years later, Stieglitz again photographed a skyscraper in progress. The horses are gone, and the cleaner, sharper composition shows how much his style had modernized as well.

In between, he had tracked progress in a series from his studio window. He had also tracked change in the journal Camera Work and two galleries. 291, named for its address on Fifth Avenue, opened with the new century, right after he met Steichen. Later came American Place. Their names, in each case a location, make two statements about an evolving American century. One speaks of its birth, the other of Stieglitz's position at the epicenter of a broad, compelling ideal—what one print calls Spiritual America.

Modernize me

Like Steichen, Stieglitz moved between old world and new, but in the opposite direction. No wonder he saw things from an American point of view. Born in 1864 and raised on the elegant Upper East Side, he had a German education and lived for several years in France. Only in 1991 did he return to America, where he encountered a New York still becoming a modern city, and of course he photographed it right away. On marrying he traveled again back to Europe. Of the three men, only Stieglitz experienced and photographs the cost of World War I, but then his family had an estate in France.

Nonetheless, he was mostly making and promoting art in America, much like Edith Halpert, including the origins of abstraction. Even from the first, it seems like a more modern America than Steichen's—and a more modern art. Horses may carry traffic down snowy and dusty streets past stone buildings, but without hiding behind a blur. With The Steerage in 1907, he still has an older documentary style. However, he has produced the signature image of America as tensely and anxiously welcoming change. The crossed diagonals of pillars, hull, and empty gangplank barely push back the surging humanity. The photographer's art lies in both the diagonals and the surge.

His approach to abstraction helps to modernize him, and its controlled expressionism lies between Steichen's brooding and Strand's clarity. It includes the Music of a storm, Rebecca Strand's torso, and shadows across a lake. The black birches of Dancing Trees could pass for a negative's reversal of black and white in the interest of drama and composition. And of course there is Georgia O'Keeffe, whom he met in 1916. He lingers over her taut neck, breasts, and hands. He shows her stroking a wheel or skull, as well as in front of her own painting.

He does not need to choose between portraying her as an object of desire and an autonomous creator, a work of art and an artist. It is hard to know who most inspired whom to undertake a more modern art. "Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand" hopes to say much the same about Stieglitz, Steichen, and Strand. They all make art out of people, urban architecture, and art. They all photograph themselves, with distinct notions of dashing masculinity. They photograph each other, with distinct notions of what counts as flattery.

Still, the show's three rooms amount more to greatest hits than a parade of fresh insights. It cannot do justice to any of the three. It cannot do justice to Stieglitz as a center. To do that, it would have to include many more, like Clarence White, who passed through Stieglitz's galleries and journals. Other photographers of the time turn up in an adjacent room, with no particular theme or order. Other artists turn up, too, in photos—like the romance of Marsden Hartley in a fashionable overcoat.

One could write off the entirety as having no more excuse than the shared initial letter S. However, museums are making creative use these days of their own resources, and this idea may work best small. With a full roster of photographers, the show would quickly descend into documentation. With just three, it would spin off into three separate blockbusters. Instead, one gets to experience the successive births of American Modernism in photography. And Stieglitz gets to hold its center.

"Stieglitz, Steichen, Strand" ran at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through April 10, 2011. A related review looks at Edward Steichen in his years at Condé Nast. A personal aside: my father shared a dental practice with his brother—and a shared code. When a less than bright patient arrived, he would say, "Here comes the man with a hoe."