Jackson Pollock Meets Ronald Reagan

John Haberin New York City

The American Century: Part II

Part I of "The American Century" was a drag. Not even Fred Astaire at its center could make the art dance. Worse, the Whitney never convinced me that he was lining up to dance with the artists. The American century held five decades of wallflowers.

Part II looks like fun, right from the museum lobby. Painterly abstraction hangs next to Ellsworth Kelly's sharp planes of color. Arcing across that two-story space, just up from a row of electric lights as sculpture, they look anything but mere period pieces. Tony Oursler's eyeball watches them all in fear, tension, and pleasure.

Only something is wrong. Even the fearsome, all-seeing eye was once up for sale. By the time I made it through this awkward, perplexing exhibition, I came to fear that it is watching only TV.

The flag on high

What a display it is as one enters—eclectic, messy, dialogic, and very much focused on art. Once critics chortled over the triumph of American painting in the second half of a dizzying century. This show will celebrate the triumph of American culture—not to mention the American museum—diverse, messy, and outrageous. For that one moment, one begs for it. But then one gets off the elevator to the first galleries. In an instant, the visitor and the art of 1950 are put in their place.

One sees two oddly chosen Pollocks, hung far apart, as if to cut off the exchange between them and the viewer. In the unflattering, soft lighting, they become unreadable entrance signs for the two gallery doorways nearby. Each lies right next to five small drip canvases also from 1950, hung in columns, like Abstract Expressionist totem poles or African sculpture. The curator, Lisa Phillips, has taken over the entire museum like an archaeologist for a dead religion.

She has set one of the big paintings 90 degrees from its usual orientation, as proof she can unearth the past. In that same gallery, photos document Pollock's breakthrough show at Betty Parsons, where it hung just that way. The juxtaposition of media finishes off whatever formalism the top floor's traditional, rectilinear entrance gallery may leave.

What has happened? American art has become an icon, as totem and as a record of its time. And that is the point of this strangely absorbing, frustrating show. Just as in Part I, the less critically the Whitney celebrates American culture, the duller it gets, the more it needs what the Museum of Modern Art calls "Making Choices" in its own multi-part survey exhibition. Only this time the slimier it gets, the better it evokes the unsettled art of the century's end.

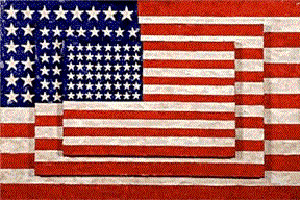

Some choices reflect a natural bias to the museum's own holdings. One can hardly mind a magnificent, yards-wide painting by Lee Krasner. One woman, at least, had no fear of her husband's aspirations, even with Krasner and Pollock or Krasner's drips. Jasper Johns, with his flags and white targets but not repetitions by Johns in gray or Johns in prints, goes well indeed with Frank Stella and his brutal reference to painting as icon, Die Fahne Hoch. For others, such as Barnett Newman or Rothko, I do wish the Whitney had looked beyond its cellars.

Either way, though, the poor lighting spells death. The square shades of black by Ad Reinhardt appear colorless. Either way, too, the Whitney's choices echo the uncanny dream of an American icon. Next to a well-known Woman hangs a little-known painting of Marilyn Monroe in the same style. Willem de Kooning, one must understand, analyzed woman at second hand, too, just like Andy Warhol—through the aspirations of American culture.

Cultural history without history lectures

As one proceeds past this first generation, any remaining traces of formalism fall entirely away. Even the shape of the galleries shifts, back to Part I's chaos of walls, nooks, corridors, and videos. Phillip's heart lies in the madness of America, and remarkably, it almost starts to work. This show comes into its own as it at last reaches the 1970s, for all along it was imposing a conception of art at a century's close. All along, it is imagining the changed role of art in postmodern culture.

Alcoves try explicitly to run down history and culture, without help from Robert Frank and The Americans, and they mostly come a clunker. Some seem trite and irrelevant. Videos exhort children to duck and cover in fear of the bomb. I never could connect them to the art of their time—or even to my own childhood. Some alcoves, conversely, seem too familiar, as if people, power, ideals, and conflicts were put through a blender. Jimi Hendrix plays near lava lamps, the space race, and politics. The Rolling Stones playing behind a work of art add nothing, because the Stones played behind every moment of my life.

The show makes a case for art as cultural event—not in the history lectures, but in the art itself. When the Whitney comes to the art boom and art politics of the 1970s, it becomes moving, even horrific. Nan Goldin's photos and slide shows take one back to the brief East Village gallery boom and the drug users one climbed over to find it. I experienced again the shock of city streets in the Reagan era's agonies. Those terrible days introduced me to art, and they changed art's relationship to pompous institutions like the Whitney Museum.

By begging—if not bagging—questions of enduring merit, the show gets off the hook in another way, too. Why fight over who is included and who is left out? When I see Mike Kelley and his high-school class, I no longer object. America loves shallow celebrities, the show seems to say, so why balk at one more?

Other artists acquire a bite they lacked in their own time. Was David Salle perhaps out for fame, fortune, and shock? Now he seems darkly emblematic of his time, like the shock one feels thinking back. Really good stuff, like Jenny Holzer in digital media and crawl screens or Cindy Sherman with her Untitled Film Stills, fit right in. It is about time I heard their cryptic warnings.

Art as documentation comes into its own in another way, too, that it could not in Part I. So much recent art, after all, has lived for the moment. Robert Smithson dancing on Spiral Jetty or Chris Burden rolling on broken glass end up as more than documentary footage. They leave the intentional video art, like Bill Viola's, in the dust. Gary Hill's video dismembers a body in miniature (a theme he still pursues), as if to echo the show's love of body parts and shock. And Yoko Ono with her screams sounds more and more like the cries of an artist, a major artist, not the no-talent spoiler everyone hated in mourning the Beatles.

The Simpsons ten years after

I cannot justify every miserable bias. A fascination with pop culture goes all too well with the Whitney's long love affair with the Beats, including a crusty monster by Jay DeFeo. It accounts for artists new to me, attempts to address ethnic gaps in the art scene. It means that we get Eva Hesse at her squishiest, since her more formal triumphs might spoil the party. It means that one meets the first work that got an artist attention, even if it makes artists as fine as Robert Ryman look pathetic.

The show sees through the eyes of Reagan's America in another way, too. It shares not just the former president's short attention span, but also his nasty chauvinism. American culture starts to stand for its times, just when European art was attaining its greatest influence in half a century. A Whitney staffer should check out Sensation at the Brooklyn Museum or other views of the Britpack.

Criticism and philosophy have been merging art into history for some time now. Like an overgrown child, art has needed acculturation. Writers have suggested how deeply artists such as were embedded in American myths. How easily their protests, anxiety, and detachment turned into the triumph of modern man. And art critics mean all this as something less than a compliment.

Art reduces easily to history, the history of a commodity culture. Postmodern critics use that to see through a nation and its heroes. The old school actually used it to celebrate America's triumph, in the world and the marketplace. This show turns things around. Art does not become politically charged. Rather, history itself becomes part of American culture, up for sale.

Paradoxically, the Whitney likes the Simpsons, who get a monitor in the stairwell. Yet its uncritical eye reduces art to a textbook duller than any scholar. In a final paradox, however, that deadening tells something about America that I thrilled once again to hear.

This show distorts American art and culture badly. It also evokes beautifully and sadly a distortion the century has barely lived through. I am dying to go back, but I am scared to death to face it once again. How fortunate that the Whitney will get more than one chance to review its collection.

Part II of "The American Century: Art and Culture 1900–2000" ran through February 2, 2000, at The Whitney Museum of American Art. Part I ran through August 22, 1999.