MoMA, too, Sings America

John Haberin New York City

American Modern: Hopper, O'Keeffe, and Eliot Porter

Ansel Adams had seen some of America's most impressive places when he took time out for An American Place. He would have had to take an elevator to the seventeenth floor, at 509 Madison Avenue in midtown Manhattan. Even for him, it was no ordinary journey. But then this was no ordinary gallery.

Adams photographed the dealer, Alfred Stieglitz, at his desk by a window, as intent as a medieval scholar or a scientist. Here, the photograph says, one is present at the creation of an American art, and it begins with light. Now the Museum of Modern Art makes the same boast, with "American Modern: Hopper to O'Keeffe." It sheds light on the museum's inability to display its permanent collection, almost to the point of distaste for art, and it makes a sad commentary on its latest and most shameless expansion plans. As a welcome companion show, Eliot Porter, who must have taken the elevator that year himself, begins to find his due.

Making excuses for America

It was 1938, the year of his book on the John Muir Trail, and Alfred Stieglitz had inspired Adams to open his own gallery in San Francisco five years before. Stieglitz's gallery, his second in New York, lacked the obvious grandeur of Yosemite, but Adams made a point of the depth and clarity that he, like Carleton Watkins before him, brought to the West. The dealer sits at at the end of a narrow passage, between paintings and a tall window bathed in sunshine. By then, Stieglitz had photographed such fellow artists as Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin. By then, too, he had reached an accommodation of sorts between his own neuroses and his love of Georgia O'Keeffe and O'Keeffe drawings. In his photographs from the 1920s, her long fingers linger over one another or the shining wheel of a motorcar.

At the gallery, though, Stieglitz seems equally absorbed in his work, the art, and the light. Charles Sheeler, who called a painting of a desk by a window his Self-Portrait, would have understood. So would Arthur Dove, who called his assemblage of a lens, mirrored glass, steel, and nails a portrait of Stieglitz. So would Edward Hopper, who captured both sunlight and the night. Hopper's etchings could almost serve as a rebuttal to Hopper drawings at the Whitney, in their broader America landscape and growing sense of isolation. Where there is light, they say, there must also be shadows.

All these greet one at MoMA, and they describe the museum's history as well. Hopper's House by the Railroad was the very first work to enter the collection. Not a bad start, especially for a museum known not for American art, but for defining Modernism. Of the more than one hundred works on display now, several came as gifts as early as 1930, the year after MoMA's founding, and it dedicated a show to Americans soon after. Many have become staples of art history and popular culture, like Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth. Nearly all belong to the permanent collection, and they are only a selection.

They also occupy little-noticed galleries for temporary exhibitions on the second floor. Upstairs, the Modern celebrates a legendary exhibition in the 1930s, of Walker Evans, and Stieglitz had a competing dealer in Edith Halpert as well. Somehow, though, MoMA has little space even now for forty-five years of American art—even counting six tiny prints by Evans of New York's architecture, closely cropped to the point of abstraction. Remember its cramped but beloved old building? What if ten years ago it had knocked the place down and built a new and larger MoMA, to make more room for art? Oh, wait.

One can always make excuses, including excuses for the latest plan that would destroy MoMA's neighbors and turn only a fraction of the added space into display space. The Whitney, too, keeps struggling with what to do with its enduring collection of American art. It has had its deep overview of "An American Century," themed shows like "Real/Surreal," a more diverse rehanging as "At the Dawn of a New Age," and concentrations on single artists. Yet all of them have had a point, and all of them have felt at home on Madison Avenue. Not one amounted to an apology. One will have to see whether its new home in the Meatpacking District, in a design by Renzo Piano, can do more.

"American Modern" falls somewhere between a reclamation project, a crowd pleaser, and a holding action, and it has the strengths and weaknesses of all three. It contains true surprises, like O'Keeffe's orchid in shimmering pastel. It uses pairings to call attention to women, as with Margaret Bourke-White's intricate photograph beside Louis Lozowick's more ominous industrial machinery, Imogen Cunningham's still-life photograph beside the less stark space of Paul Strand, or Helen Torr's shadowy exterior beside Dove's equally cryptic building amid the willows. For Florine Stettheimer in her 1933 family portrait, flowers and familiar skyscrapers float in an almost metallic white like giant stars. Still, even with Berenice Abbott and Dorothea Lange, it will hardly answer feminist critics. It has even fewer African Americans or Mexican Americans, and here folk art and design mean Elie Nadelman.

An ambivalent Modernism

This is not rewriting history, but tweaking at the edges. It is not simply business as usual, though. For one thing, it treats photography on a par with painting and sculpture. I might never have known that Ben Shahn worked closely from photographs, as with a painting of handball players. For another, it has no interest in chronology and not all that much in individual artists. It gives special attention only to O'Keeffe, Hopper, Charles Burchfield, Stuart Davis, and Sheeler, with the rest as "context."

The first three receive a wall or more to themselves, perhaps to build a case for their character as loners. Hopper sees a woman's clothed rear end through a window, but even as voyeur he finds a world hesitant to disclose more. O'Keeffe moves so easily between landscape and abstraction that one forgets which is which, another of the show's guiding ideas. Evening Star looks like a Kenneth Noland target fifty years before the fact, only better. Meanwhile Davis, Sheeler, and Demuth are widely dispersed, less as twentieth-century masters than as touchstones. The display runs largely by subject—most especially still life, women in sculpture, the city, and rural America.

Those themes cut across styles, media, and even decades. Even within a single work, juxtapositions can bring revelations, if now and then at the expense of particulars. When the nighttime colors of Joseph Stella hang near Miles Spencer and George Ault, realism and Cubism alike become a kind of magic realism. Across the room, George Bellows and others fill out an uncanny and unsettling picture of New York. When William Zorach's bust of his daughter and her cat sits near grown women by Nadelman, Gaston Lachaise, and Robert Laurent, one can find sexual tensions beneath their blocky outlines in marble, bronze, granite, and alabaster. Then again, one might see only the old charges against Modernism and its "primitivism," of appropriation and leveling.

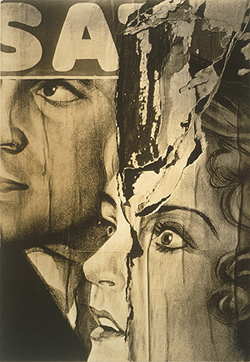

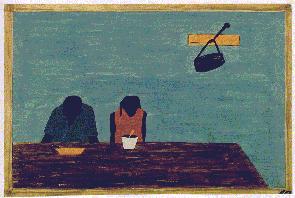

If so, MoMA may welcome the charge. It sees a constant in American art, in an openness to experiment and yet an ambivalence to Modernism. And it sees that ambivalence as uncertainty about modernity itself and a changing America—to which one might add, with regret, a changing Museum of Modern Art. The curators, Kathy Curry and Esther Adler, point to the absence of people in Sheeler's Detroit. They could well point, too, to the portraits of transience in Evans's Torn Movie Poster, Burchfield's rail lines, or Lange's open road. The six excerpts from The Migration Series, by Jacob Lawrence, describe a flight to freedom, but also African Americans caught between railway stations, train tracks, labor camps, temporary urban shelter, and white America.

If so, MoMA may welcome the charge. It sees a constant in American art, in an openness to experiment and yet an ambivalence to Modernism. And it sees that ambivalence as uncertainty about modernity itself and a changing America—to which one might add, with regret, a changing Museum of Modern Art. The curators, Kathy Curry and Esther Adler, point to the absence of people in Sheeler's Detroit. They could well point, too, to the portraits of transience in Evans's Torn Movie Poster, Burchfield's rail lines, or Lange's open road. The six excerpts from The Migration Series, by Jacob Lawrence, describe a flight to freedom, but also African Americans caught between railway stations, train tracks, labor camps, temporary urban shelter, and white America.

The contrasts within a theme suggest an art in transit as well, and one should never forgot how much of Modernism came to America in the form of artists in transit, as European exiles. The transitions are most rapid and dazzling with still life, starting with dark outlines in photographs. There Strand's elegant realism matches Steichen's near abstraction point for point. Turn one's head, and one moves to the freshness of Demuth's watercolors, with their echoes of Paul Cézanne, or Peter Blume's cramped and bewildering jug on a log. Round the corner, and one comes to Davis's eggbeater beside a mandolin, with echoes of both a Matisse tabletop and Picasso's guitars. Gerald Murphy's stricter geometry is only a step away.

Look to the facing wall, and one has glowing prints by Edward Weston and Man Ray. The latter's leaves hold out fruit as the seeds of new and uncertain life. Was there, then, a native American Cubism, an American realism, or an American Surrealism? Maybe all of them, but only with Abstract Expressionism yet to come. And maybe none of them has much space in MoMA's architecture. Still, if only for now, all of them take shape in "American Modern."

The art of wildness

In 1938, then, Ansel Adams photographed Alfred Stieglitz in his mid-Manhattan gallery. Eliot Porter exhibited with Stieglitz that same year, and Adams had introduced them. For all that, the two photographers can easily seem polar opposites. Adams's western vistas came to define not just an American photography, as with Mitch Epstein today, but a nation. Porter, who had studied engineering and taught biochemistry, placed the nation under close scrutiny, like a scientist. The contrasts multiply ever so quickly—the artist and the naturalist, the genius and the amateur, the museum fixture and the fixture in Sierra Club publicity.

The comparison has not often redounded to Porter's benefit, but they were closer than one may remember. Adams, too, was a dedicated preservationist, and he has appeared on his share of calendars. Porter had taken up photography from childhood, and Stieglitz encouraged him to quit the faculty of Harvard Medical School to pursue it. Now a gallery helps to redress the balance, but by embracing the differences. Its thirty-two photos date from 1940 to 1975, but chiefly from the 1960s—the decade of In Wildness Is the Preservation of the Earth, published by the Sierra Club, and Porter's years as a Club director. It also affords a closer look at both the artist and nature.

Where Porter, who died in 1990, most often worked in series, for books devoted to a single location, the show delights in pairings. They might be a fence in Aspen besides hemlocks in the Adirondacks, Antarctic ice floes beside desert slopes in Utah, or enormous twisted and whitened tree roots beside classical columns and female carvings from Luxor and Greece. While Porter after 1945 shifted largely to color photography, then often seen as less than art, including a series with Ellen Auerbach, roughly half here is in black and white. (He had turned to the new and demanding medium of dye-transfer prints, in accord with the habits of an experimental photographer or, if you prefer, laboratory scientist.) The result tilts to formalism, concerned for light, shape, texture, and the picture plane. It is also an art aware of the human investment in living on the edge of nature.

The show begins in Monument Valley, Utah, with the contrasting textures of soft earth, rippling sand, and jagged stone, all overseen by distant totemic rocks. Twenty-five years later in Colorado, the image has grown still denser, in layers of depth from bare young trees to thick bushes to grassy hills. The objects closest to the foreground serve as containers for depth, like black trees nature's own light box. Rocks at Yellowstone take a few seconds of looking to becomes the sides of a great valley, with a waterfall in the distance. They are about looking and not illusion all the same.

Porter is always something of a scientist, asking how. How exactly do trees branch and bud, and how do inorganic surfaces evolve from the action of water, wind, and sun? What do spreading roots record long after the tree is gone, and how do nests take sustenance and protection from surrounding leaves? He reserves the brightest colors for birds, in quest of their behavior in eating, feeding young, pairing off, and taking flight. He photographs a bird with its wings spread, as if physically as well as visually caught in flight. The images also recalls the history of photography, when Eadweard Muybridge thought to ask whether a horse's feet ever leave the ground at once.

Born in 1901, Porter does have his old-fashioned side. Where Adams, a year younger, can sacrifice specifics in the quest for something larger, Porter can get wrapped up in detail—really two sides of American Romanticism, in the sublime and the picturesque. Like Adams, too, he deserves a place in the American modern, as in this past year's "Artist's Choice" from MoMA's permanent collection by Trisha Donnelly. The show helps see him as contemporary as well, with that dense undergrowth only slowly giving way to specificity and depth. Much the same debunking of American myths is everywhere these days, as with photographs by Robert Adams of his neighborhood at night or with painters close to trees by day. In wildness there is science, but also art.

"American Modern: Hopper to O'Keeffe" ran at The Museum of Modern Art through January 26, 2014, Eliot Porter at Paula Cooper through August 16, 2013. The review of Porter first appeared in a slightly different form in New York Photo Review.