4.4.25 — Control Freak

Piet Mondrian at the Guggenheim makes a fine introduction to a classic of modern art. Still, with only thirteen works, it can be little more than an introduction—especially when it comes to the stern, lively, off-kilter abstract paintings that made him someone to remember.

As I noted last time, you can look back to Mondrian’s 1996 retrospective and my review then, which looks further, too, at the significance of works in series within modern art. Allow me, then, an excerpt, with links to more.

Maybe I am imagining it, but it does not hurt an artist’s rep if the name begins with an M. Monet, Matisse, Miro . . . but Mondrian? Yes, indeed. The painter known above all for his austerity has taken everyone by surprise, including the critics. They have found the exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art a little less deep and a lot more fun than anyone could have expected. Mondrian turns out to be as joyful and decorative an heir of Monet as anyone could want.

I am not (altogether) joking. The reviews could well have been written in collaboration. They start with Piet Mondrian, unmarried at his death, with the thin features and wire spectacles of a European schoolmaster. Could this man, they marvel, have delivered the flash of a painting called Broadway Boogie-Woogie? The museum’s own bookstore managers panic at keeping up with the unanticipated demand snaking out the door.

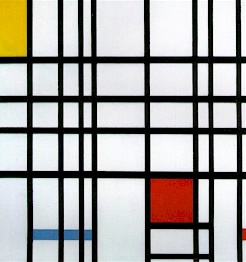

I have to admit to the same relieved surprise. Mondrian’s work looks imposingly regular, its near-symmetry earned the hard way. A small square of primary color just balances a large square in another corner, which in turn could easily teeter over the edge of confusion without a saving black bar someplace else. Taking it all in is like holding one’s breath.

This show comes like one long, relaxing exhale. It begins with brooding landscapes and modern still life painted in Holland. In these and later paintings influenced by the Analytic Cubism of Picasso and Braque, outlines escape to take on an active life of their own. The delicacy of the lines resembles nothing in Picasso, however.

Also as in Cubism, the corners of the image appear to have dropped out. In this way, ordinary things and abstract forms can float, suspended for contemplation. The fragmentation slowly opens up Mondrian’s art to fields of calm, steady white.

In his best-known paintings, a firm rectangle returns, the areas of bring color expand, and the lines reach out to the painting’s unframed edge. Under their pull, the center no longer holds. Rather than enforcing symmetry, Mondrian kept on finding novel means to break it. He always starts with a form and lets his paint stretch it apart.

Later still, after the painter’s move to America, the color rectangles stay bright but grow smaller. They take on increasing activity, like blips on a crawl screen. Shortly before his death, they indeed come to recall the staccato accents of New York City thoroughfares. With the tribute of appropriation, Melissa Gordon even likens them to the front page of a newspaper

This show’s secret turns out after all to lie in that formula for a blockbuster. It asks that one reconsider why art sought the appearance of anonymity. It asks why symmetry breaking like his had such vitality. Paradoxically, modern art has depended for its color and variety on works in series.

Read more, now in a feature-length article on this site.